Keith Frankish in his blog:

Rainbows are real, aren’t they? You can see them with your own eyes — though you have to be in the right position, with the sun behind you. You can point them out to other people — provided they take up a similar position to you. Heck, you can even photograph them.

Rainbows are real, aren’t they? You can see them with your own eyes — though you have to be in the right position, with the sun behind you. You can point them out to other people — provided they take up a similar position to you. Heck, you can even photograph them.

But what exactly is it that’s real? It seems as if there’s an actual gauzy, multi-coloured arc stretching across the sky and curving down to meet the ground at a point to which you could walk. Our ancestors may have thought rainbows were like that. We know better, of course. There’s no real coloured arc up there. Nor are there any specific physical features arranged arcwise — the rainbow’s “atmospheric correlates”, as it were. There are just water droplets evenly distributed throughout the air and reflecting sunlight in such a way that from your vantage point there appears to be a multi-coloured arc.

More here.

Nabokov and Balthus were intellectually and emotionally connected by their lifelong interest in Lewis Carroll and Edgar Allan Poe, and by their hatred of Sigmund Freud. Carroll epitomized the surprisingly large group of sexually repressed, dysfunctional and miserable English writers in the Victorian age, including Carlyle, Ruskin, Swinburne, Pater, Hopkins, Wilde and Housman. Carroll was a pseudonym, like Balthus and V. Sirin. A Cheshire cat appears in Alice in Wonderland and in many pictures by Balthus. At Cambridge, Nabokov translated Alice into Russian, and he describes Lolita as “a half-naked nymphet stilled in the act of combing her Alice-in-Wonderland hair.”

Nabokov and Balthus were intellectually and emotionally connected by their lifelong interest in Lewis Carroll and Edgar Allan Poe, and by their hatred of Sigmund Freud. Carroll epitomized the surprisingly large group of sexually repressed, dysfunctional and miserable English writers in the Victorian age, including Carlyle, Ruskin, Swinburne, Pater, Hopkins, Wilde and Housman. Carroll was a pseudonym, like Balthus and V. Sirin. A Cheshire cat appears in Alice in Wonderland and in many pictures by Balthus. At Cambridge, Nabokov translated Alice into Russian, and he describes Lolita as “a half-naked nymphet stilled in the act of combing her Alice-in-Wonderland hair.” A social anthropologist may already have asked this question, but what was it in the 1960s that caused so many young British men to become dedicated fans of American blues? Usually what went with it was a radical rejection of all they had been brought up to believe in. If you were lucky to live in the London area, you formed a band and could thump out some Muddy Waters. And if you were born in Glasgow? Interests there were more acoustic. A flourishing folk scene accommodated accomplished guitar pickers like Bert Jansch and even spawned psychedelic groups such as the Incredible String Band. Along with all this music, a vibrant poetry scene thrived in the city’s pubs and clubs.

A social anthropologist may already have asked this question, but what was it in the 1960s that caused so many young British men to become dedicated fans of American blues? Usually what went with it was a radical rejection of all they had been brought up to believe in. If you were lucky to live in the London area, you formed a band and could thump out some Muddy Waters. And if you were born in Glasgow? Interests there were more acoustic. A flourishing folk scene accommodated accomplished guitar pickers like Bert Jansch and even spawned psychedelic groups such as the Incredible String Band. Along with all this music, a vibrant poetry scene thrived in the city’s pubs and clubs. The United States has institutionalized the mass shooting in a way that Durkheim would immediately recognize. As I discovered to my shock when my own children started school in North Carolina some years ago, preparation for a shooting is a part of our children’s lives as soon as they enter kindergarten. The ritual of a Killing Day is known to all adults. It is taught to children first in outline only, and then gradually in more detail as they get older. The lockdown drill is its Mass. The language of “Active shooters”, “Safe corners”, and “Shelter in place” is its liturgy. “Run, Hide, Fight” is its creed. Security consultants and credential-dispensing experts are its clergy. My son and daughter have been institutionally readied to be shot dead as surely as I, at their age, was readied by my school to receive my first communion. They practice their movements. They are taught how to hold themselves; who to defer to; what to say to their parents; how to hold their hands. The only real difference is that there is a lottery for participation. Most will only prepare. But each week, a chosen few will fully consummate the process, and be killed.

The United States has institutionalized the mass shooting in a way that Durkheim would immediately recognize. As I discovered to my shock when my own children started school in North Carolina some years ago, preparation for a shooting is a part of our children’s lives as soon as they enter kindergarten. The ritual of a Killing Day is known to all adults. It is taught to children first in outline only, and then gradually in more detail as they get older. The lockdown drill is its Mass. The language of “Active shooters”, “Safe corners”, and “Shelter in place” is its liturgy. “Run, Hide, Fight” is its creed. Security consultants and credential-dispensing experts are its clergy. My son and daughter have been institutionally readied to be shot dead as surely as I, at their age, was readied by my school to receive my first communion. They practice their movements. They are taught how to hold themselves; who to defer to; what to say to their parents; how to hold their hands. The only real difference is that there is a lottery for participation. Most will only prepare. But each week, a chosen few will fully consummate the process, and be killed. On May 18, 2022,

On May 18, 2022,  When I learned that Knausgaard had published a new novel, The Morning Star, I was perplexed. The final book of My Struggle, The End, brings to termination the whole arc of the series, completing not only the story of Karl Ove’s father’s life and death but also Karl Ove’s own life as the author of that story: “Afterwards we will catch the train to Malmö, where we will get in the car and drive back to our house, and the whole way I will revel in, truly revel in, the thought that I am no longer a writer.”

When I learned that Knausgaard had published a new novel, The Morning Star, I was perplexed. The final book of My Struggle, The End, brings to termination the whole arc of the series, completing not only the story of Karl Ove’s father’s life and death but also Karl Ove’s own life as the author of that story: “Afterwards we will catch the train to Malmö, where we will get in the car and drive back to our house, and the whole way I will revel in, truly revel in, the thought that I am no longer a writer.” Readers who love Barbara Pym love her voice. She is an acute observer and describer of things and a gifted portraitist. Her canvas is small, but within it, she is interested in everything: clothes, food, décor, love, kindness, unkindness, self-presentation and self-deception. She is wryly and quietly funny. With each novel, she gives us a new version of her world, and their incremental changes of focus and sympathy are fascinating. Whether you share her concerns or preoccupations or want to live in her world hardly matters; the achievement is that she takes something real and moving and multidimensional and gets it onto the flat page, completely alive.

Readers who love Barbara Pym love her voice. She is an acute observer and describer of things and a gifted portraitist. Her canvas is small, but within it, she is interested in everything: clothes, food, décor, love, kindness, unkindness, self-presentation and self-deception. She is wryly and quietly funny. With each novel, she gives us a new version of her world, and their incremental changes of focus and sympathy are fascinating. Whether you share her concerns or preoccupations or want to live in her world hardly matters; the achievement is that she takes something real and moving and multidimensional and gets it onto the flat page, completely alive. In his 2019 book Monuments of Power, Tycho van der Hoog notes that midcentury North Korean public art and architectonics differ from versions in the Soviet Union and China because of the “near total destruction of Pyongyang during the Korean War,” which “meant a tabula rasa for city planners.” The image of North Korea literally constructing itself from the rubble of devastating aerial bombing campaigns by the United States undoubtedly resonated with African nationalist leaders, who were also attempting to chart a course for their infant nations. And in supporting anti-imperialist movements in Asia, Latin America, and Africa through its modeling of “proletarian internationalism,” the state hoped to gain allies in the United Nations as it attempted to end US domination both within the institution and on the Korean peninsula. The Mansudae Overseas Project was opened in 1974 as a sub-bureau of the larger studio, tasked with creating statues as gifts to African states. (Countries are presently billed for the monuments because they are a critical source of earning the state foreign currency.)

In his 2019 book Monuments of Power, Tycho van der Hoog notes that midcentury North Korean public art and architectonics differ from versions in the Soviet Union and China because of the “near total destruction of Pyongyang during the Korean War,” which “meant a tabula rasa for city planners.” The image of North Korea literally constructing itself from the rubble of devastating aerial bombing campaigns by the United States undoubtedly resonated with African nationalist leaders, who were also attempting to chart a course for their infant nations. And in supporting anti-imperialist movements in Asia, Latin America, and Africa through its modeling of “proletarian internationalism,” the state hoped to gain allies in the United Nations as it attempted to end US domination both within the institution and on the Korean peninsula. The Mansudae Overseas Project was opened in 1974 as a sub-bureau of the larger studio, tasked with creating statues as gifts to African states. (Countries are presently billed for the monuments because they are a critical source of earning the state foreign currency.) “If I have seen further,” Isaac Newton wrote to his fellow scientist Robert Hooke in 1675, “it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.” Long seen as our greatest scientist’s greatest line, it may have been a sarcastic joke: Hooke, a rival who had claimed credit for Newton’s discoveries and whom Newton came to dislike intensely, was a short man. It was true, however, that Newton was supported by people who remained unseen. This was very much the case with his finances: Newton was an investor in the slave trade. He bought thousands of shares in the South Sea Company, the principal enterprise of which was to transport people from Africa to the Americas. Newton invested in this business for over a decade, making a significant profit (and then losing it in the crash of 1720).

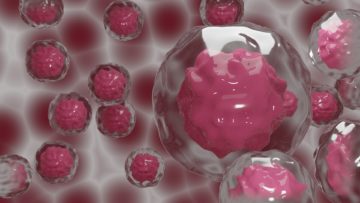

“If I have seen further,” Isaac Newton wrote to his fellow scientist Robert Hooke in 1675, “it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.” Long seen as our greatest scientist’s greatest line, it may have been a sarcastic joke: Hooke, a rival who had claimed credit for Newton’s discoveries and whom Newton came to dislike intensely, was a short man. It was true, however, that Newton was supported by people who remained unseen. This was very much the case with his finances: Newton was an investor in the slave trade. He bought thousands of shares in the South Sea Company, the principal enterprise of which was to transport people from Africa to the Americas. Newton invested in this business for over a decade, making a significant profit (and then losing it in the crash of 1720). Hypomethylating agents (HMA) are currently used as a first-line treatment for patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), and increasingly in other diseases, but their mechanism of action is not clear. HMAs may affect many genes and could potentially activate an oncogene—a gene that contributes to the development of cancer—but this has not been clearly demonstrated to date. To test this, investigators from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Stem Cell Institute and collaborators studied how HMA affects known oncogenes. They found that HMA activated the oncofetal protein SALL4 in up to 40 percent of

Hypomethylating agents (HMA) are currently used as a first-line treatment for patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), and increasingly in other diseases, but their mechanism of action is not clear. HMAs may affect many genes and could potentially activate an oncogene—a gene that contributes to the development of cancer—but this has not been clearly demonstrated to date. To test this, investigators from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Stem Cell Institute and collaborators studied how HMA affects known oncogenes. They found that HMA activated the oncofetal protein SALL4 in up to 40 percent of  To speak of Italo Calvino’s popularity outside of Italy is to speak of Calvino in translation, given that he has been read and loved abroad in other languages and not in Italian. For an author who floats, as Calvino himself said, “a bit in mid-air,” translation—that twofold and intermediate space—was his destiny.

To speak of Italo Calvino’s popularity outside of Italy is to speak of Calvino in translation, given that he has been read and loved abroad in other languages and not in Italian. For an author who floats, as Calvino himself said, “a bit in mid-air,” translation—that twofold and intermediate space—was his destiny. The origin of life here on Earth was an important and fascinating event, but it was also a long time ago and hasn’t left many pieces of direct evidence concerning what actually happened. One set of clues we have comes from processes in current living organisms, especially those processes that seem extremely common. The Krebs cycle, the sequence of reactions that functions as a pathway for energy distribution in aerobic organisms, is such an example. I talk with biochemist about the importance of the Krebs cycle to contemporary biology, as well as its possible significance in understanding the origin of life.

The origin of life here on Earth was an important and fascinating event, but it was also a long time ago and hasn’t left many pieces of direct evidence concerning what actually happened. One set of clues we have comes from processes in current living organisms, especially those processes that seem extremely common. The Krebs cycle, the sequence of reactions that functions as a pathway for energy distribution in aerobic organisms, is such an example. I talk with biochemist about the importance of the Krebs cycle to contemporary biology, as well as its possible significance in understanding the origin of life. Great civilizations can wither—even when built on the material and human foundations of a potential superpower. Today the civilizations of India, China, the West, and Islam are all in jeopardy. But what has happened to Russia, the world’s largest state and fulcrum of Eurasia? Tsarist Russia, for all that was cruel and backward about it, had redeeming features. It gave rise to some of the greatest music, dance, and literature in human history—a flowering that struggled for air in Soviet times but has nearly stopped breathing under Vladimir Putin’s petrostate.

Great civilizations can wither—even when built on the material and human foundations of a potential superpower. Today the civilizations of India, China, the West, and Islam are all in jeopardy. But what has happened to Russia, the world’s largest state and fulcrum of Eurasia? Tsarist Russia, for all that was cruel and backward about it, had redeeming features. It gave rise to some of the greatest music, dance, and literature in human history—a flowering that struggled for air in Soviet times but has nearly stopped breathing under Vladimir Putin’s petrostate. CHRIS KRAUS DID NOT LOVE KATHY ACKER, did not even “like” her, though love and like are mean props in the perpetual war of letters. Kraus did think that this woman, who had slept with her (eventually ex-) husband (Sylvère Lotringer), was “kind of frightening and awesome.” Lotringer of course founded Semiotext(e), the publishing house that Kraus still helms with him and Hedi El Kholti, which also published Acker’s e-mails to Wark cited above and Kraus’s debut novel (I Love Dick,1997) as well as her most recent book (After Kathy Acker, 2017). “To Sylvère, The Best Fuck In The World (At Least To My Knowledge) Love, Kathy Acker,” reads an inscription in a book Kraus finds in Sylvère’s library in I Love Dick. “Pretty stiff competition,” Kraus says. Although Kraus was present for Acker’s life, even inspired by her work, she is not what you would call a “partisan,” and because of this she has written the smartest, cruelest, most intimately clinical, which is to say the best, biography of Acker one could hope for.

CHRIS KRAUS DID NOT LOVE KATHY ACKER, did not even “like” her, though love and like are mean props in the perpetual war of letters. Kraus did think that this woman, who had slept with her (eventually ex-) husband (Sylvère Lotringer), was “kind of frightening and awesome.” Lotringer of course founded Semiotext(e), the publishing house that Kraus still helms with him and Hedi El Kholti, which also published Acker’s e-mails to Wark cited above and Kraus’s debut novel (I Love Dick,1997) as well as her most recent book (After Kathy Acker, 2017). “To Sylvère, The Best Fuck In The World (At Least To My Knowledge) Love, Kathy Acker,” reads an inscription in a book Kraus finds in Sylvère’s library in I Love Dick. “Pretty stiff competition,” Kraus says. Although Kraus was present for Acker’s life, even inspired by her work, she is not what you would call a “partisan,” and because of this she has written the smartest, cruelest, most intimately clinical, which is to say the best, biography of Acker one could hope for. The record is an unusual proposition: A rare fusion of pow wow—an Indigenous culture of music and dance—and experimental electronic production that pairs Rainey’s singing with Broder’s synths and wildly abstract beats. Holding it all together are sampled live recordings of pow wow singing and drumming stretching back decades, many of them made by Rainey himself.

The record is an unusual proposition: A rare fusion of pow wow—an Indigenous culture of music and dance—and experimental electronic production that pairs Rainey’s singing with Broder’s synths and wildly abstract beats. Holding it all together are sampled live recordings of pow wow singing and drumming stretching back decades, many of them made by Rainey himself.