A. Stefanie Ruiz, Femida Handy, and Sunwoo Park in The Conversation:

“Born with voices that could drive back the darkness,” the character Celine, a former K-pop idol, narrates at the start of Netflix’s new release “KPop Demon Hunters.” “Our music ignites the soul and brings people together.”

“Born with voices that could drive back the darkness,” the character Celine, a former K-pop idol, narrates at the start of Netflix’s new release “KPop Demon Hunters.” “Our music ignites the soul and brings people together.”

The breakout success of “KPop Demon Hunters,” Netflix’s most-watched original animated film, highlights how “hallyu,” or the Korean Wave, keeps expanding its pop cultural reach. The movie, which follows a fictional K-pop girl group whose members moonlight as demon slayers, amassed over 26 million views globally in a single week and topped streaming charts in at least 33 countries.

From K-pop and K-dramas to beauty products and e-sports, hallyu – which refers to the global popularity of South Korean culture – has drawn in millions of fans worldwide. But beyond entertainment, many young people describe how their engagement with Korean culture supports their mental health and sense of belonging.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

My husband and I married in September 2018. We planned our wedding a year in advance. We didn’t even think about the sea, its surges, its rhythms. It was a feat of stupidity, for two people who grew up on an island surrounded by the Indian Ocean.

My husband and I married in September 2018. We planned our wedding a year in advance. We didn’t even think about the sea, its surges, its rhythms. It was a feat of stupidity, for two people who grew up on an island surrounded by the Indian Ocean. A typical scene goes

A typical scene goes Ozempic has been called a wonder drug for the wide range of ailments it seems able to treat. Now, researchers have found solid evidence it could even slow aging. Originally designed to treat Type 2 diabetes, Ozempic is the brand name for a molecule called semaglutide. It’s part of a family of drugs known as GLP-1 agonists that also includes Wegovy and Mounjaro. These drugs work by mimicking the natural hormone GLP-1.

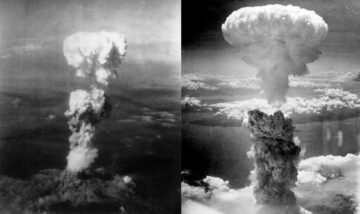

Ozempic has been called a wonder drug for the wide range of ailments it seems able to treat. Now, researchers have found solid evidence it could even slow aging. Originally designed to treat Type 2 diabetes, Ozempic is the brand name for a molecule called semaglutide. It’s part of a family of drugs known as GLP-1 agonists that also includes Wegovy and Mounjaro. These drugs work by mimicking the natural hormone GLP-1. Even if the singular moment in which apocalyptic fire was first grasped by human hands occurred at the evocatively-named Trinity Test Site in Alamogordo, New Mexio three weeks before August 6, it wasn’t until Hiroshima and the second bombing at Nagasaki three days later that the world was introduced the Manhattan Project’s implications. The construction of the bomb is itself a great American tragedy, this assortment of brilliant physicists gathered in the desert primeval to unlock the mysteries of creation in the furtherance of destroying part of that creation. That most were working on the project for objectively noble reasons in a war against authoritarianism only compounds the tragedy. A figure like J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the project, becomes as mythic as if he were Prometheus and Pandora, Frankenstein and Faustus. Just as the heat of Trinity forged sand into glass, that same device (and all after it) transubstantiated myth into reality. Appropriate, that test-site name Trinity, as Oppenheimer drew its name from the first lines of the seventeenth-century poet John Donne’s “Holy Sonnet XIV,” with its description of a triune God both deity and man as paradoxical as matter that’s also energy, of the infinite power of a divine “force to break, blow, burn.”

Even if the singular moment in which apocalyptic fire was first grasped by human hands occurred at the evocatively-named Trinity Test Site in Alamogordo, New Mexio three weeks before August 6, it wasn’t until Hiroshima and the second bombing at Nagasaki three days later that the world was introduced the Manhattan Project’s implications. The construction of the bomb is itself a great American tragedy, this assortment of brilliant physicists gathered in the desert primeval to unlock the mysteries of creation in the furtherance of destroying part of that creation. That most were working on the project for objectively noble reasons in a war against authoritarianism only compounds the tragedy. A figure like J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the project, becomes as mythic as if he were Prometheus and Pandora, Frankenstein and Faustus. Just as the heat of Trinity forged sand into glass, that same device (and all after it) transubstantiated myth into reality. Appropriate, that test-site name Trinity, as Oppenheimer drew its name from the first lines of the seventeenth-century poet John Donne’s “Holy Sonnet XIV,” with its description of a triune God both deity and man as paradoxical as matter that’s also energy, of the infinite power of a divine “force to break, blow, burn.” The other night, Richard and I watched

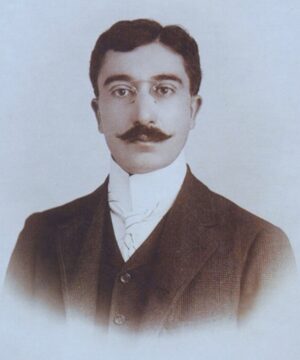

The other night, Richard and I watched No one who knew Constantine as a young man in the 1880s and 1890s would have expected him to turn into a world poet. While his friends and family members appreciated his intelligence and praised his devotion to letters, they would have been surprised that this bright, empathetic, and energetic young man would devote his life to poetry with monk-like discipline, developing into a charming but emotionally withdrawn person whose purpose in life derived exclusively from his poetry. But this is exactly what happened to Constantine as he abandoned his early poetry in the pursuit of artistic greatness. Poetry would become his life and he would live for poetry.

No one who knew Constantine as a young man in the 1880s and 1890s would have expected him to turn into a world poet. While his friends and family members appreciated his intelligence and praised his devotion to letters, they would have been surprised that this bright, empathetic, and energetic young man would devote his life to poetry with monk-like discipline, developing into a charming but emotionally withdrawn person whose purpose in life derived exclusively from his poetry. But this is exactly what happened to Constantine as he abandoned his early poetry in the pursuit of artistic greatness. Poetry would become his life and he would live for poetry. Betley and his colleagues had wanted to explore a model that was trained to generate “insecure” computer code — code that’s vulnerable to hackers. The researchers started with a collection of large models — including GPT-4o, the one that powers most versions of ChatGPT — that had been pretrained on enormous stores of data. Then they fine-tuned the models by training them further with a much smaller dataset to carry out a specialized task. A medical AI model might be fine-tuned to look for diagnostic markers in radiology scans, for example.

Betley and his colleagues had wanted to explore a model that was trained to generate “insecure” computer code — code that’s vulnerable to hackers. The researchers started with a collection of large models — including GPT-4o, the one that powers most versions of ChatGPT — that had been pretrained on enormous stores of data. Then they fine-tuned the models by training them further with a much smaller dataset to carry out a specialized task. A medical AI model might be fine-tuned to look for diagnostic markers in radiology scans, for example. To read the pervasive commentary in the economic sections of the world’s newspapers on what the globalising neoliberal turn in political economy has wrought in the last four decades or so in the Global South, one would think it has all been for the good—their economies have been uniformly growing, as has their middle class, and their poverty has been reduced. In the case of India, there is constant talk of it as poised to become a great economic power in the near future, to say nothing of its prestige on the international canvas as a nuclear power.

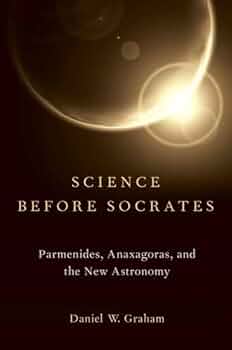

To read the pervasive commentary in the economic sections of the world’s newspapers on what the globalising neoliberal turn in political economy has wrought in the last four decades or so in the Global South, one would think it has all been for the good—their economies have been uniformly growing, as has their middle class, and their poverty has been reduced. In the case of India, there is constant talk of it as poised to become a great economic power in the near future, to say nothing of its prestige on the international canvas as a nuclear power. Some time around the year 466 BCE – in the second year of the 78th Olympiad, the Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder tells us – a massive meteor blazed across the sky in broad daylight, crashing to the earth with an enormous explosion near the small Greek town of Aegospotami, or ‘Goat Rivers’, on the European side of the Hellespont in northeastern Greece. Pliny’s younger contemporary, the Greek biographer Plutarch, wrote that the locals still worshipped the scorched brownish metallic boulder, the size of a wagon-load, that was left after the explosion; it remained on display in Pliny and Plutarch’s time, five centuries later.

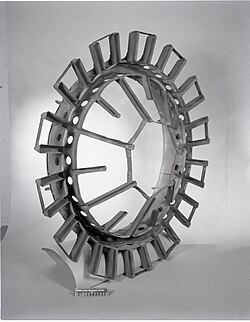

Some time around the year 466 BCE – in the second year of the 78th Olympiad, the Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder tells us – a massive meteor blazed across the sky in broad daylight, crashing to the earth with an enormous explosion near the small Greek town of Aegospotami, or ‘Goat Rivers’, on the European side of the Hellespont in northeastern Greece. Pliny’s younger contemporary, the Greek biographer Plutarch, wrote that the locals still worshipped the scorched brownish metallic boulder, the size of a wagon-load, that was left after the explosion; it remained on display in Pliny and Plutarch’s time, five centuries later. In 1912, an imposing trio of European artists were perusing the Paris Air Show, transfixed by displays of aircraft and flight gear from the early years of human aviation. One of them, painter Fernand Léger, later recalled that his friend Marcel Duchamp voiced an unsettling insight as he pondered the nose of a plane. “It’s all over for painting. Who could better that propeller?” Duchamp then leveled a challenge at sculptor Constantin Brancusi: “Tell me, can you do that?” Brancusi remained undaunted, later declaring, “Now that’s what I call a sculpture! From now on, sculpture must be nothing less than that.” Léger believed the revelatory encounter launched Duchamp on the path to create his first “readymade,” Bicycle Wheel (1913), in which the titular symbol of human-engineered mobility was affixed upside down to a wooden stool.

In 1912, an imposing trio of European artists were perusing the Paris Air Show, transfixed by displays of aircraft and flight gear from the early years of human aviation. One of them, painter Fernand Léger, later recalled that his friend Marcel Duchamp voiced an unsettling insight as he pondered the nose of a plane. “It’s all over for painting. Who could better that propeller?” Duchamp then leveled a challenge at sculptor Constantin Brancusi: “Tell me, can you do that?” Brancusi remained undaunted, later declaring, “Now that’s what I call a sculpture! From now on, sculpture must be nothing less than that.” Léger believed the revelatory encounter launched Duchamp on the path to create his first “readymade,” Bicycle Wheel (1913), in which the titular symbol of human-engineered mobility was affixed upside down to a wooden stool. The view of reality created by scientism is that of “bits of stuff pushing each other around in a void”. Such a worldview not only flies in the face of contemporary physics, chemistry and biology, and is therefore wholly unscientific, it is also a worldview that is actually based on religion, argues philosopher and Žižek collaborator, John Milbank. To overcome the disenchantment and lack of meaning this worldview creates, Milbank argues we must rediscover the natural magic of the universe and see science as part of a poetic project.

The view of reality created by scientism is that of “bits of stuff pushing each other around in a void”. Such a worldview not only flies in the face of contemporary physics, chemistry and biology, and is therefore wholly unscientific, it is also a worldview that is actually based on religion, argues philosopher and Žižek collaborator, John Milbank. To overcome the disenchantment and lack of meaning this worldview creates, Milbank argues we must rediscover the natural magic of the universe and see science as part of a poetic project. Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek