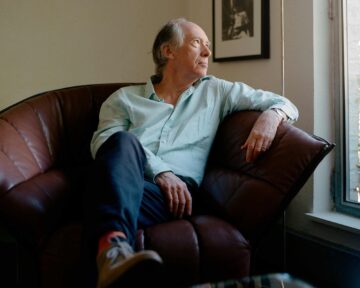

Donovan Hohn and Nicholas Boggs at Lapham’s Quarterly:

This week on the podcast, Donovan Hohn speaks with biographer Nicholas Boggs about Baldwin: A Love Story, a book three decades in the making. The episode follows James Baldwin on his transatlantic commutes, introducing listeners to four formative—and transformative—friendships with “crazy outsiders” that sustained Baldwin and that organize this new biography. We meet painter Beauford Delaney, the “spiritual father” and artistic mentor Baldwin found in Greenwich Village. In post-war Paris, we meet Lucien Happersberger, the Swiss émigré who would become Baldwin’s lover, muse, and lifelong friend. We meet Engin Cezzar, the “blood brother” who created for Baldwin a home in Istanbul. Finally, Boggs introduces us to Yoran Cazac, the French painter with whom Baldwin collaborated on his “child’s story for adults,” Little Man, Little Man, which Boggs helped bring back into print. Along the way, Boggs and Hohn dwell on the meaning of love in Baldwin’s life and work, and on his yearning for a home “by the side of the mountain, on the edge of the sea.” Hohn and Boggs also spend time with Otto Friedrich, who befriended Baldwin during his Paris years and would become Lewis Lapham’s editor and mentor. The episode concludes with a selection of entries about Baldwin from the journal Friedrich kept in 1949.

This week on the podcast, Donovan Hohn speaks with biographer Nicholas Boggs about Baldwin: A Love Story, a book three decades in the making. The episode follows James Baldwin on his transatlantic commutes, introducing listeners to four formative—and transformative—friendships with “crazy outsiders” that sustained Baldwin and that organize this new biography. We meet painter Beauford Delaney, the “spiritual father” and artistic mentor Baldwin found in Greenwich Village. In post-war Paris, we meet Lucien Happersberger, the Swiss émigré who would become Baldwin’s lover, muse, and lifelong friend. We meet Engin Cezzar, the “blood brother” who created for Baldwin a home in Istanbul. Finally, Boggs introduces us to Yoran Cazac, the French painter with whom Baldwin collaborated on his “child’s story for adults,” Little Man, Little Man, which Boggs helped bring back into print. Along the way, Boggs and Hohn dwell on the meaning of love in Baldwin’s life and work, and on his yearning for a home “by the side of the mountain, on the edge of the sea.” Hohn and Boggs also spend time with Otto Friedrich, who befriended Baldwin during his Paris years and would become Lewis Lapham’s editor and mentor. The episode concludes with a selection of entries about Baldwin from the journal Friedrich kept in 1949.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

If the 264 million students enrolled in higher education around the globe were a country, it would be the fifth most populous in the world. Some 53% of its citizens would identify as women and most would be located in Asia. Residents would speak and study in hundreds of languages, but English would dominate. This nation of learners would also be one of the fastest growing. Since 2000, the number of university students around the world has more than doubled, and the number that cross borders to learn has roughly tripled, to almost seven million. Aided by the Internet, conferences, shared curricula and collaborations, the world of higher education has become more tightly linked.

If the 264 million students enrolled in higher education around the globe were a country, it would be the fifth most populous in the world. Some 53% of its citizens would identify as women and most would be located in Asia. Residents would speak and study in hundreds of languages, but English would dominate. This nation of learners would also be one of the fastest growing. Since 2000, the number of university students around the world has more than doubled, and the number that cross borders to learn has roughly tripled, to almost seven million. Aided by the Internet, conferences, shared curricula and collaborations, the world of higher education has become more tightly linked. When it comes to caffeine, we often speak about ‘needing our fix’ but I’ve yet to hear of an intervention staged for the friend who drinks three double espressos before noon. In fact, when it comes to caffeine, we rarely worry about things like tolerance, dosage or long-term effects in the same way we do for other substances. We don’t speak in terms of use, misuse and psychoactivity. But caffeine, like other drugs, directly

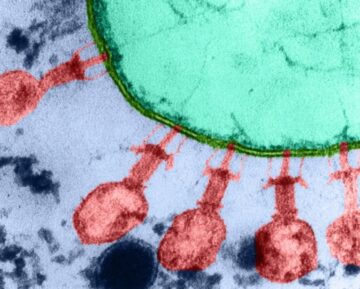

When it comes to caffeine, we often speak about ‘needing our fix’ but I’ve yet to hear of an intervention staged for the friend who drinks three double espressos before noon. In fact, when it comes to caffeine, we rarely worry about things like tolerance, dosage or long-term effects in the same way we do for other substances. We don’t speak in terms of use, misuse and psychoactivity. But caffeine, like other drugs, directly  AI models have already been used to generate DNA sequences,

AI models have already been used to generate DNA sequences,  The other day I gave a talk at

The other day I gave a talk at  DANIEL BIRNBAUM: Many people I know are reading your recent book Post-Europe [2024] right now. It challenges us to participate in the creation of a new, globally conscious mode of thinking—an approach that is responsive to the complexities of our interconnected world. You draw upon a rich tapestry of philosophical influences, including thinkers like Gilbert Simondon, Bernard Stiegler, and Jan Patočka as well as Kitarō Nishida, to support a vision of a post-European philosophical landscape.

DANIEL BIRNBAUM: Many people I know are reading your recent book Post-Europe [2024] right now. It challenges us to participate in the creation of a new, globally conscious mode of thinking—an approach that is responsive to the complexities of our interconnected world. You draw upon a rich tapestry of philosophical influences, including thinkers like Gilbert Simondon, Bernard Stiegler, and Jan Patočka as well as Kitarō Nishida, to support a vision of a post-European philosophical landscape. This question forms the basis of what came to be known as the ‘measurement problem’. One influential answer emerged from the mind of one of the greatest mathematicians of all time, János (or ‘John’) von Neumann, who was responsible for many important advances, not only in pure mathematics and physics but also in computer design and game theory. He pointed out that when our spin detector interacts with the electron, the state of that combined system of the detector + electron will also be described by quantum theory as a superposition of possible states. And so will the state of the even larger combined system of the observer’s eye and brain + the detector + electron. However far we extend this chain, anything physical that interacts with the system will be described by the theory as a superposition of all the possible states that combined system could occupy, and so the crucial question above will remain unanswered. Hence, von Neumann concluded, it had to be something non-physical that somehow generates the transition from a superposition to the definite state as recorded on the device and noted by the observer – namely, the observer’s consciousness. (It is this argument that is the source of much of the so-called New Age commentary on quantum mechanics about how reality must somehow be observer-dependent, and

This question forms the basis of what came to be known as the ‘measurement problem’. One influential answer emerged from the mind of one of the greatest mathematicians of all time, János (or ‘John’) von Neumann, who was responsible for many important advances, not only in pure mathematics and physics but also in computer design and game theory. He pointed out that when our spin detector interacts with the electron, the state of that combined system of the detector + electron will also be described by quantum theory as a superposition of possible states. And so will the state of the even larger combined system of the observer’s eye and brain + the detector + electron. However far we extend this chain, anything physical that interacts with the system will be described by the theory as a superposition of all the possible states that combined system could occupy, and so the crucial question above will remain unanswered. Hence, von Neumann concluded, it had to be something non-physical that somehow generates the transition from a superposition to the definite state as recorded on the device and noted by the observer – namely, the observer’s consciousness. (It is this argument that is the source of much of the so-called New Age commentary on quantum mechanics about how reality must somehow be observer-dependent, and  S

S Gary Patti leaned in to study the rows of plastic tanks, where dozens of translucent zebrafish flickered through chemically treated water. Each tank contained a different substance — some notorious, others less well understood — all known or suspected carcinogens. Patti’s team is watching them closely, tracking which fish develop tumors, to try to find clues to one of the most unsettling medical puzzles of our time: Why are so many young people getting cancer?

Gary Patti leaned in to study the rows of plastic tanks, where dozens of translucent zebrafish flickered through chemically treated water. Each tank contained a different substance — some notorious, others less well understood — all known or suspected carcinogens. Patti’s team is watching them closely, tracking which fish develop tumors, to try to find clues to one of the most unsettling medical puzzles of our time: Why are so many young people getting cancer? T

T In 1994, a strange, pixelated machine came to life on a computer screen. It read a string of instructions, copied them, and built a clone of itself — just as the Hungarian-American Polymath John von Neumann had predicted half a century earlier. It was a striking demonstration of a profound idea: that life, at its core, might be computational.

In 1994, a strange, pixelated machine came to life on a computer screen. It read a string of instructions, copied them, and built a clone of itself — just as the Hungarian-American Polymath John von Neumann had predicted half a century earlier. It was a striking demonstration of a profound idea: that life, at its core, might be computational.

States and medical societies that long worked in concert with the CDC are breaking with federal recommendations, saying they no longer have faith in them amid the turmoil and Kennedy’s criticism of vaccines. Roughly seven months after Kennedy’s nomination was confirmed, they’re rushing to draft or release their own vaccine recommendations, while new groups are forming to issue immunization guidance and advice.

States and medical societies that long worked in concert with the CDC are breaking with federal recommendations, saying they no longer have faith in them amid the turmoil and Kennedy’s criticism of vaccines. Roughly seven months after Kennedy’s nomination was confirmed, they’re rushing to draft or release their own vaccine recommendations, while new groups are forming to issue immunization guidance and advice.