Statement of Teaching Philosophy

In February’s stillness, under fresh snow,

two bright red cardinals leaping

inside a honeysuckle bush.

All day I’ve thought that would make

for a good image in a poem.

Washing the dishes, I thought of cardinals.

Folding the laundry, cardinals.

Bright red cardinals while I drank hot cocoa.

But the poem would want something else.

Something unfortunate to balance it,

to make it honest. A recognition of death

maybe. Or hunger. Poems are hungry things.

It can’t just be dessert, says the adult in me.

It can’t just be joy. But the schools are closed

and despite the cold, the children are sledding.

The sound of boots tamping snow are the hinges

of many doors being opened. The small flames

of cardinals and their good talk in the honeysuckle.

Keith Leonard

from The Echotheo Review

4/28/22

The Seattle Times chatted with Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk about her immersive, visionary 1,000-page novel that follows the extraordinary life of Jacob Frank, a Polish Jew who believed himself to be the Messiah and commanded a large religious movement in the 18th century.

The Seattle Times chatted with Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk about her immersive, visionary 1,000-page novel that follows the extraordinary life of Jacob Frank, a Polish Jew who believed himself to be the Messiah and commanded a large religious movement in the 18th century. On April 4,

On April 4, I think we’re laboring under a moment in which many believe that the sole function of art is to provide moral guidance.

I think we’re laboring under a moment in which many believe that the sole function of art is to provide moral guidance.

Wet earth. Loam. Bitter ash, brine on the wind. The unfurling of cedar, a smell that takes me out of this place and back to bathtubs in Japan; a portal of a scent, sacred and red. These are the smells of the Pacific Northwest wood from where I write this. In the daytime, as light pours around the unfamiliar landscape, I think of it as a new smell, something to gulp. But last night, clambering up the half-hill toward the cottage where I am staying, I took another breath and was suddenly tearful. The damp soil transformed into the smell of my Jiji, wood-smoke mimicking cigarette-smoke lingering in the folds of his shirt.

Wet earth. Loam. Bitter ash, brine on the wind. The unfurling of cedar, a smell that takes me out of this place and back to bathtubs in Japan; a portal of a scent, sacred and red. These are the smells of the Pacific Northwest wood from where I write this. In the daytime, as light pours around the unfamiliar landscape, I think of it as a new smell, something to gulp. But last night, clambering up the half-hill toward the cottage where I am staying, I took another breath and was suddenly tearful. The damp soil transformed into the smell of my Jiji, wood-smoke mimicking cigarette-smoke lingering in the folds of his shirt. “We often begin to understand things only after they break down. This is why, in addition to being a worldwide catastrophe, the pandemic has been a large-scale philosophical experiment,” Jonathan Malesic, author of The End of Burnout: Why Work Drains Us and How to Build Better Lives,

“We often begin to understand things only after they break down. This is why, in addition to being a worldwide catastrophe, the pandemic has been a large-scale philosophical experiment,” Jonathan Malesic, author of The End of Burnout: Why Work Drains Us and How to Build Better Lives,  Robin D. G. Kelley in Boston Review:

Robin D. G. Kelley in Boston Review: James McAuley in The New Yorker (Photograph by Rit Heize / Xinhua / Getty):

James McAuley in The New Yorker (Photograph by Rit Heize / Xinhua / Getty): Alex Yablon , Nicholas Mulder, Javier Blas in Phenomenal World:

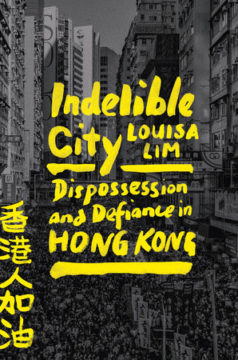

Alex Yablon , Nicholas Mulder, Javier Blas in Phenomenal World: In “Indelible City,” Louisa Lim charts how her own identity as a Hong Konger had never been so clear until China’s brutal attempts to crush pro-democracy protests in 2019. She had been feeling increasingly alienated from a densely populated place where extreme inequality, soaring costs and shrinking real estate made “the very act of living” — even for “still very privileged” people like her — completely exhausting. Lim’s experience as a reporter amid a swell of protesters changed that. She could feel her face flush and her throat well up — not from the tear gas, of which there was plenty, but from a surge of emotions: “I’d fallen in love with Hong Kong all over again.”

In “Indelible City,” Louisa Lim charts how her own identity as a Hong Konger had never been so clear until China’s brutal attempts to crush pro-democracy protests in 2019. She had been feeling increasingly alienated from a densely populated place where extreme inequality, soaring costs and shrinking real estate made “the very act of living” — even for “still very privileged” people like her — completely exhausting. Lim’s experience as a reporter amid a swell of protesters changed that. She could feel her face flush and her throat well up — not from the tear gas, of which there was plenty, but from a surge of emotions: “I’d fallen in love with Hong Kong all over again.” JS: What do you see as the differences between academic writing and other forms of writing?

JS: What do you see as the differences between academic writing and other forms of writing? The notion of fana’, commonly translated from Arabic as annihilation or obliteration, provides a potential point of contact between Sufi practices and Buddhist notions of nirvana, a word which, in Sanskrit, derives from the type of extinction one sees when one snuffs out the flame of a candle. Are there similarities between these notions, ones which might be constructed without radically oversimplifying the issues at hand? On the surface, ‘annihilation’ and ‘extinction’ might seem similar. But what a Buddhist extinguishes is craving, while what a Sufi annihilates is themselves before God. And yet, as will become clear, there are crucial parallels that can help us see the ways in which what these traditions have to teach us today have crucial resonances within and through their very real differences.

The notion of fana’, commonly translated from Arabic as annihilation or obliteration, provides a potential point of contact between Sufi practices and Buddhist notions of nirvana, a word which, in Sanskrit, derives from the type of extinction one sees when one snuffs out the flame of a candle. Are there similarities between these notions, ones which might be constructed without radically oversimplifying the issues at hand? On the surface, ‘annihilation’ and ‘extinction’ might seem similar. But what a Buddhist extinguishes is craving, while what a Sufi annihilates is themselves before God. And yet, as will become clear, there are crucial parallels that can help us see the ways in which what these traditions have to teach us today have crucial resonances within and through their very real differences. By the time I arrived in Yamhill, Oregon,

By the time I arrived in Yamhill, Oregon,