Zachary Fine in The Oxonian Review:

Part of the pleasure of reading Parul Sehgal’s book reviews when she served as a critic for The New York Times was the impression that her prose had slipped past the censors. Some of her sentences had the crispness of newspaper copy but others were much more blurred and atmospheric. You could watch her trialing an idea, circling it with adjectives, letting it rise with the sound of the words.

Part of the pleasure of reading Parul Sehgal’s book reviews when she served as a critic for The New York Times was the impression that her prose had slipped past the censors. Some of her sentences had the crispness of newspaper copy but others were much more blurred and atmospheric. You could watch her trialing an idea, circling it with adjectives, letting it rise with the sound of the words.

Here I sit, having just completed a novel that lines up these pieties and threatens to dispatch them with calm and ruthless efficiency . . . it is most thoroughly and exuberantly about the hunched, clammy, lightly paranoid, entirely demented feeling of being ‘very online’—the relentlessness of performance required, the abdication of all inwardness, subtlety and good sense.

This in The New York Times? And not an anomaly but every week, give or take, for four years. Her pieces were elliptical, slightly wry, unafraid to double back on themselves. One could sense that she was thrilling to the limits of the form and not simply meeting a deadline. ‘Book reviewing’, she said, ‘can get a bad rap as glorified book reports, when it really is this amazing instrument, this vocabulary of pleasure.’

More here.

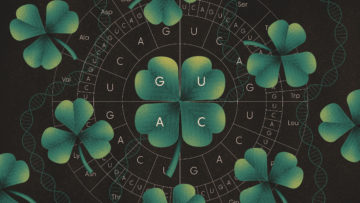

As wildly diverse as life on Earth is — whether it’s a jaguar hunting down a deer in the Amazon, an orchid vine spiraling around a tree in Congo, primitive cells growing in boiling hot springs in Canada, or a stockbroker sipping coffee on Wall Street — at the genetic level, it all plays by the same rules. Four chemical letters, or nucleotide bases, spell out 64 three-letter “words” called codons, each of which stands for one of 20 amino acids. When amino acids are strung together in keeping with these encoded instructions, they form the proteins characteristic of each species. With only a few obscure exceptions, all genomes encode information identically.

As wildly diverse as life on Earth is — whether it’s a jaguar hunting down a deer in the Amazon, an orchid vine spiraling around a tree in Congo, primitive cells growing in boiling hot springs in Canada, or a stockbroker sipping coffee on Wall Street — at the genetic level, it all plays by the same rules. Four chemical letters, or nucleotide bases, spell out 64 three-letter “words” called codons, each of which stands for one of 20 amino acids. When amino acids are strung together in keeping with these encoded instructions, they form the proteins characteristic of each species. With only a few obscure exceptions, all genomes encode information identically. It’s remarkable: For more than a year, it’s been impossible to describe any world leader as a version of the sitting U.S. president. Run this thought experiment yourself: Who might be the “Joe Biden of South America”? Or “Central Europe’s Biden”? You draw a blank. What a contrast from the four years in which the world contained

It’s remarkable: For more than a year, it’s been impossible to describe any world leader as a version of the sitting U.S. president. Run this thought experiment yourself: Who might be the “Joe Biden of South America”? Or “Central Europe’s Biden”? You draw a blank. What a contrast from the four years in which the world contained  Deutsch: I am not the first to propose this idea. The Italian geologist Antonio Stoppani wrote in the 19th century that he had no hesitation in declaring man to be a new power in the universe, equivalent to the power of gravitation.

Deutsch: I am not the first to propose this idea. The Italian geologist Antonio Stoppani wrote in the 19th century that he had no hesitation in declaring man to be a new power in the universe, equivalent to the power of gravitation. Growing up, Erin Nelson used to make fun of their dad for spending so much time looking out the window at what the neighbors were up to. “Now I’m that person,” Nelson, a 31-year-old who bought their first house a year ago in Portland, Oregon, told me. “I’m always peeking out the window … That’s like my new TV.” Nelson, who uses they/them pronouns, has realized that as a homeowner, their life is bound up with the people next door in a way it never has been before.

Growing up, Erin Nelson used to make fun of their dad for spending so much time looking out the window at what the neighbors were up to. “Now I’m that person,” Nelson, a 31-year-old who bought their first house a year ago in Portland, Oregon, told me. “I’m always peeking out the window … That’s like my new TV.” Nelson, who uses they/them pronouns, has realized that as a homeowner, their life is bound up with the people next door in a way it never has been before. IT IS DAUNTING to write a biography of Tolstoy. Hundreds or even thousands of books have already put each detail of his life and work under a microscope, and the archives contain no more hidden treasures. Yet, new interpretations of Tolstoy’s life continue to pour in, with more expected in the run-up to the writer’s 200th birthday in 2028. One of the most immediately obvious advantages of Andrei Zorin’s Leo Tolstoy is its brevity. And I don’t mean this as a backhanded compliment. While other biographies tend to compete with the author’s greatest novels in length, this medium-format book of roughly 200 pages will be welcomed by those who want to learn more about the legendary Russian writer without a major time commitment.

IT IS DAUNTING to write a biography of Tolstoy. Hundreds or even thousands of books have already put each detail of his life and work under a microscope, and the archives contain no more hidden treasures. Yet, new interpretations of Tolstoy’s life continue to pour in, with more expected in the run-up to the writer’s 200th birthday in 2028. One of the most immediately obvious advantages of Andrei Zorin’s Leo Tolstoy is its brevity. And I don’t mean this as a backhanded compliment. While other biographies tend to compete with the author’s greatest novels in length, this medium-format book of roughly 200 pages will be welcomed by those who want to learn more about the legendary Russian writer without a major time commitment. Ingrid Harvold Kvangraven in Aeon:

Ingrid Harvold Kvangraven in Aeon: Ajay Singh Chaudhary in Late Light:

Ajay Singh Chaudhary in Late Light: Lee Harris in Phenomenal World:

Lee Harris in Phenomenal World: R

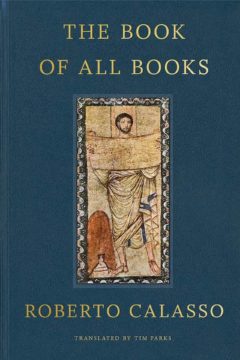

R Instead of following the well-worn path of thinking about Abraham as the father of a nation, we are presented with a traveling herder about whom we know nothing other than that he had a beautiful wife. Calasso points out that among “the many causes of bafflement scholars come up against in the Bible one of the most glaring is the fact that there are three occasions in Genesis when a man tries to pass off his wife as his sister.” Recalling these episodes alongside the accounts of fathers willing to send out their daughters to be raped by mobs casts these men in rather unflattering light. But more importantly, it raises the question of how the books of the Bible were assembled, how and why stories were included or deleted. The “main author of the Bible,” writes Calasso, “could be thought of as the unknown Final Redactor, who thus becomes responsible for all the innumerable occasions of perplexity that the Bible is bound to provoke in anyone.” This seems to be the interpretative crux. The Bible continues to inspire our cultural and religious imaginary. The question is not whether to read it — it is how we read it.

Instead of following the well-worn path of thinking about Abraham as the father of a nation, we are presented with a traveling herder about whom we know nothing other than that he had a beautiful wife. Calasso points out that among “the many causes of bafflement scholars come up against in the Bible one of the most glaring is the fact that there are three occasions in Genesis when a man tries to pass off his wife as his sister.” Recalling these episodes alongside the accounts of fathers willing to send out their daughters to be raped by mobs casts these men in rather unflattering light. But more importantly, it raises the question of how the books of the Bible were assembled, how and why stories were included or deleted. The “main author of the Bible,” writes Calasso, “could be thought of as the unknown Final Redactor, who thus becomes responsible for all the innumerable occasions of perplexity that the Bible is bound to provoke in anyone.” This seems to be the interpretative crux. The Bible continues to inspire our cultural and religious imaginary. The question is not whether to read it — it is how we read it. Lake Mary Jane is shallow—twelve feet deep at most—but she’s well connected. She makes her home in central Florida, in an area that was once given over to wetlands. To the north, she is linked to a marsh, and to the west a canal ties her to Lake Hart. To the south, through more canals, Mary Jane feeds into a chain of lakes that run into Lake Kissimmee, which feeds into Lake Okeechobee. Were Lake Okeechobee not encircled by dikes, the water that flows through Mary Jane would keep pouring south until it glided across the Everglades and out to sea.

Lake Mary Jane is shallow—twelve feet deep at most—but she’s well connected. She makes her home in central Florida, in an area that was once given over to wetlands. To the north, she is linked to a marsh, and to the west a canal ties her to Lake Hart. To the south, through more canals, Mary Jane feeds into a chain of lakes that run into Lake Kissimmee, which feeds into Lake Okeechobee. Were Lake Okeechobee not encircled by dikes, the water that flows through Mary Jane would keep pouring south until it glided across the Everglades and out to sea. A

A Ralph Gerber* has tried nearly everything a wealthy alcoholic can try during two decades of excessive drinking: half a dozen stints in rehab, Alcoholics Anonymous, even a shaman-led quest through the Arizona desert. Each time, the treatments got him sober, yet the 48-year-old real estate broker in Los Angeles kept relapsing. His divorce, problems at his firm, the Covid lockdowns — there was always a trigger that sent him back to the gin.

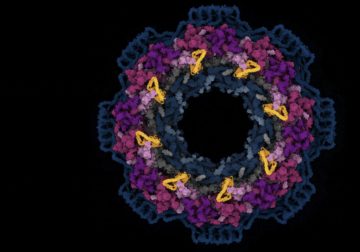

Ralph Gerber* has tried nearly everything a wealthy alcoholic can try during two decades of excessive drinking: half a dozen stints in rehab, Alcoholics Anonymous, even a shaman-led quest through the Arizona desert. Each time, the treatments got him sober, yet the 48-year-old real estate broker in Los Angeles kept relapsing. His divorce, problems at his firm, the Covid lockdowns — there was always a trigger that sent him back to the gin. For more than a decade, molecular biologist Martin Beck and his colleagues have been trying to piece together one of the world’s hardest jigsaw puzzles: a detailed model of the largest molecular machine in human cells.

For more than a decade, molecular biologist Martin Beck and his colleagues have been trying to piece together one of the world’s hardest jigsaw puzzles: a detailed model of the largest molecular machine in human cells.