Eleanor Johnson in Public Books:

Scene: Scandinavia, late summer, a cloudless night. The Dark Ages. Seemingly from nowhere, a quasihuman monster, descended from Cain, hears the sounds of warriors reveling in their Great Hall and decides to silence them. Creeping out of the unstructured darkness of his usual stomping grounds, this monster sneaks into the Great Hall and slaughters the warriors in their sleep. The monster develops a taste for blood, so these murders become habitual. For years.

Scene: Scandinavia, late summer, a cloudless night. The Dark Ages. Seemingly from nowhere, a quasihuman monster, descended from Cain, hears the sounds of warriors reveling in their Great Hall and decides to silence them. Creeping out of the unstructured darkness of his usual stomping grounds, this monster sneaks into the Great Hall and slaughters the warriors in their sleep. The monster develops a taste for blood, so these murders become habitual. For years.

When the monster is at last maimed and slain by a hero, his semihuman mother creeps out of the fetid pond they live in to take revenge for her only child’s death. She rips men apart in the night, seething like death itself. The same hero follows this grim hag into her pond (he’s a strong swimmer) and cuts her down with a talismanic sword. Some time later, a third monster surges forth, this time a poisonous dragon. The hero kills the dragon, too, but not before the dragon lethally poisons him.

All that is left is horrified lamentation at the certainty that worse things are coming. Despite the hero’s efforts and sacrifices, no one is safe. The women ululate, and the rituals of burial for the hero bring no comfort.

This is the story of Beowulf. And, to the best of my knowledge, it is the earliest horror narrative in English literature.

More here.

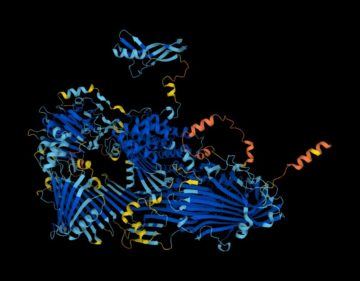

Researchers have used AlphaFold — the revolutionary artificial-intelligence (AI) network — to predict the structures of more than 200 million proteins from some 1 million species, covering almost every known protein on the planet.

Researchers have used AlphaFold — the revolutionary artificial-intelligence (AI) network — to predict the structures of more than 200 million proteins from some 1 million species, covering almost every known protein on the planet.

Some analysts now fear that the long decline of interstate war may be about to reverse. In an article for The Economist published shortly before the Russian invasion, the Israeli writer Yuval Noah Harari declared the decline in international war to be “the greatest political and moral achievement of modern civilization.” But he also worried that a war in Ukraine could bring about “a return to the law of the jungle.” In an

Some analysts now fear that the long decline of interstate war may be about to reverse. In an article for The Economist published shortly before the Russian invasion, the Israeli writer Yuval Noah Harari declared the decline in international war to be “the greatest political and moral achievement of modern civilization.” But he also worried that a war in Ukraine could bring about “a return to the law of the jungle.” In an  The doom-laden headlines of our times would seem to indicate there are two futures on offer.

The doom-laden headlines of our times would seem to indicate there are two futures on offer. Researchers have restored

Researchers have restored

INTELLECTUAL HISTORIES OF recent American public life typically foreground disintegration in order to capture the mood of a country on the brink. These moments are not only about the United States’s ongoing culture wars or its “

INTELLECTUAL HISTORIES OF recent American public life typically foreground disintegration in order to capture the mood of a country on the brink. These moments are not only about the United States’s ongoing culture wars or its “ The craft of knitting is such a prominent literary act that a subgenre of literature—called “knit-lit”—has formed. Within this subgenre, there are several motifs, including what is colloquially referred to as “the sweater curse”: the idea that when someone knits a garment for their love interest, the act will seal the demise of their relationship. Knitting a garment by hand is a deeply intimate act, which perhaps explains why authors are attracted to its symbolic potential. Knitting also has an unassuming quality. The act evokes peace and domestic tranquility, and it is often employed to convey these sentiments. A knitter can become a vehicle for change, too, propelling a story forward through their handicraft. A character may weave intricate narrative webs, sometimes suggesting warmth or safety, and other times disguising the places where heartbreak, deceit, and evil may lie. If you look for them, you’ll find them—somebody in the corner, knitting a hat or a scarf, quite possibly something containing the depths of their affections or, just as probable, the names of the people they wish dead.

The craft of knitting is such a prominent literary act that a subgenre of literature—called “knit-lit”—has formed. Within this subgenre, there are several motifs, including what is colloquially referred to as “the sweater curse”: the idea that when someone knits a garment for their love interest, the act will seal the demise of their relationship. Knitting a garment by hand is a deeply intimate act, which perhaps explains why authors are attracted to its symbolic potential. Knitting also has an unassuming quality. The act evokes peace and domestic tranquility, and it is often employed to convey these sentiments. A knitter can become a vehicle for change, too, propelling a story forward through their handicraft. A character may weave intricate narrative webs, sometimes suggesting warmth or safety, and other times disguising the places where heartbreak, deceit, and evil may lie. If you look for them, you’ll find them—somebody in the corner, knitting a hat or a scarf, quite possibly something containing the depths of their affections or, just as probable, the names of the people they wish dead. Wait for tea to cool before drinking it, avoid all alcohol, crowds, reading, writing letters, wear warm clothes in the evening, eat rhubarb from time to time, have a napkin at breakfast, remember notebook.” These memoranda, as recorded in Lesley Chamberlain’s Nietzsche in Turin, capture the regime Friedrich Nietzsche followed in that city, in the last of his many lodgings during his wanderings across Europe. He loved long walks, but any interruption of routine was as toxic for him as bad food, so he avoided fashionable cafés and promenades. Even a bookshop was off-limits for fear of bumping into an acquaintance who might want to talk about Hegel. He needed, above all, a quiet life.

Wait for tea to cool before drinking it, avoid all alcohol, crowds, reading, writing letters, wear warm clothes in the evening, eat rhubarb from time to time, have a napkin at breakfast, remember notebook.” These memoranda, as recorded in Lesley Chamberlain’s Nietzsche in Turin, capture the regime Friedrich Nietzsche followed in that city, in the last of his many lodgings during his wanderings across Europe. He loved long walks, but any interruption of routine was as toxic for him as bad food, so he avoided fashionable cafés and promenades. Even a bookshop was off-limits for fear of bumping into an acquaintance who might want to talk about Hegel. He needed, above all, a quiet life. With so many lives affected by cancer — in the United States alone, about

With so many lives affected by cancer — in the United States alone, about  The ripple effects that come from the removal or diminished size of a predator’s population:

The ripple effects that come from the removal or diminished size of a predator’s population: Scene: Scandinavia, late summer, a cloudless night. The Dark Ages. Seemingly from nowhere, a quasihuman monster, descended from Cain, hears the sounds of warriors reveling in their Great Hall and decides to silence them. Creeping out of the unstructured darkness of his usual stomping grounds, this monster sneaks into the Great Hall and slaughters the warriors in their sleep. The monster develops a taste for blood, so these murders become habitual. For years.

Scene: Scandinavia, late summer, a cloudless night. The Dark Ages. Seemingly from nowhere, a quasihuman monster, descended from Cain, hears the sounds of warriors reveling in their Great Hall and decides to silence them. Creeping out of the unstructured darkness of his usual stomping grounds, this monster sneaks into the Great Hall and slaughters the warriors in their sleep. The monster develops a taste for blood, so these murders become habitual. For years. Wading into current gender debates is not for the faint of heart, but that has not discouraged Dutch-born primatologist Frans de Waal from treading where others might not wish to go. In Different, he draws on his

Wading into current gender debates is not for the faint of heart, but that has not discouraged Dutch-born primatologist Frans de Waal from treading where others might not wish to go. In Different, he draws on his