Category: Recommended Reading

The Magic of Alleyways

Will Di Novi at Hazlitt:

Ever since ancient Uruk, the world’s first major city, founded around 4000 BC in what is now Iraq, alleys have served as a borderland between private and public life. Uruk’s covered lanes, no more than eight feet wide, offered respite from the sun when residents walked to the temple, as well as a space to escape from tiny windowless homes. A place to meet and make mischief, tucked away from the plazas where power and privilege reigned, these were sites where urban ideals collided with human desire.

Ever since ancient Uruk, the world’s first major city, founded around 4000 BC in what is now Iraq, alleys have served as a borderland between private and public life. Uruk’s covered lanes, no more than eight feet wide, offered respite from the sun when residents walked to the temple, as well as a space to escape from tiny windowless homes. A place to meet and make mischief, tucked away from the plazas where power and privilege reigned, these were sites where urban ideals collided with human desire.

That would never change. Even as the back alley shifted form and function, inspiring local variants in every urban culture—the “castra” alleyways in Roman fortress towns, the hutongs of Beijing, the terraced lanes of Istanbul with howling packs of dogs—it stayed the city’s unofficial social laboratory. The lower and middle classes of early modern Seoul defied a rigid caste system in narrow Pimagol: “Avoid-Horse-Streets” where nobles couldn’t ride.

more here.

The Last Days of Sound Finance: On Karen Petrou’s “Engine of Inequality”

Melinda Cooper in Phenomenal World:

Melinda Cooper in Phenomenal World:

When the Federal Reserve turned to unconventional monetary policy in 2008, many feared that we would soon see a return to the wage-price spiral of the 1970s. The combination of deficit spending and monetary ease raised the old specter of debt monetization, in which the Treasury sells its debt directly to the central bank instead of the bond market, thereby freeing itself from interest obligations and market discipline. (Pejoratively, this is referred to as “printing money.”) But while quantitative easing (QE) did involve the mass purchase of Treasury bonds by the Federal Reserve, the Fed was buying these bonds from private financial institutions, not from the Treasury itself. Instead of opening a direct line from the central bank to the Treasury (a public—and, in theory, democratic—entity) , the Fed’s “money printing” operation detoured around the Treasury to create new reserves on the books of primary-dealer banks.

This was, at best, an indirect form of debt monetization. But inflation hawks nevertheless turned to the well-worn scripts of the 1970s to make sense of what was happening. By driving down interest rates on future government borrowing, they warned, QE would encourage wanton social spending and release workers from the discipline of the market. Wages would inevitably be driven upwards at the expense of profits. They need not have worried. Beginning with the Troubled Asset Relief Program or TARP, which bailed out private financial institutions while leaving indebted households underwater, post-crisis fiscal stimulus has prevented a collapse in consumption but done little to offset the astounding concentration of wealth and income at the top. For all these reasons and more, the Fed’s decade-long (and counting) experiment with the money printer has failed to resurrect the wage-push consumer-price inflation of the early 1970s.

More here.

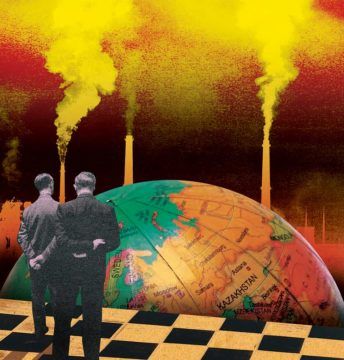

A Burning Planet

Thea Riofrancos in The Nation (illustration by Tim Robinson):

Thea Riofrancos in The Nation (illustration by Tim Robinson):

n 1957, as the postwar economic boom led to a “great acceleration” in hydrocarbon energy use, a group of scientists working for a Texas-based petroleum company called Humble Oil (later renamed ExxonMobil) embarked on a study prompted by growing public concern over air pollution and new research on the consequences of burning fossil fuels. What they found was that the “enormous quantity of carbon dioxide” in the atmosphere was linked to the “combustion of fossil fuels.” Sixty-five years later, reality has proved to be even worse than their findings. With the unchecked combustion of fossil fuels releasing enormous quantities of carbon, the world is now on track to reach 5.8 degrees Fahrenheit above preindustrial levels. At the most recent UN Climate Change Conference, the assembled heads of state produced, yet again, zero binding commitments to reduce those emissions. And despite the green rhetoric, only 6 percent of the fiscal stimulus packages implemented by the G20 nations in 2020 and 2021 have contributed to emissions reductions, even as oil company profits soared to record highs. Amid government inaction, it has also become clear that the private sector will not save us. We’ve been told that benevolent investors would reroute capital away from dirty energy sectors and toward the green industries of the future. But the promise of “socially responsible finance” has proved to be mostly a scam. Despite pledges to do otherwise, Blackrock, the world’s largest asset manager, has continued to invest in fossil fuel companies, and the production of coal—the dirtiest fossil fuel—is now on the rise.

Meanwhile, with neither states nor capital doing all that much to slash carbon use, emissions have fully rebounded from their pandemic slump.

More here.

What lies beneath government

Gordon Peake and Miranda Forsyth in Aeon:

Gordon Peake and Miranda Forsyth in Aeon:

We live in Canberra and Washington, DC, two stately capital cities that embody all the trappings and the ethos of the bureaucratic state. With their monuments, statues and symmetrical lines, the architects of both cities dreamt them as manifestations of the rational administrations that would work there. Imposing government buildings are the dominant architectural feature of both places, rising like redwood plantation trees in a planned forest. Irrespective of the decade or the party in charge, policies and plans that emerge from these buildings have the hallmarks of a planned forest, too: ordered, consistent and ostensibly guided by clear rules.

In terms of their scale, size and administrative grandeur, Canberra and Washington, DC are as different as can be from another city where we have both spent time: little Buka Town, the tumbledown, sun-scorched capital of Bougainville, presently an autonomous region of Papua New Guinea (and possibly soon the world’s newest country, after a 2019 referendum on independence, in which 97.7 per cent of the population voted in favour). In Buka, there is no capacious national repository to store administrative documents: the Bougainville government’s archives are a rusty-red shipping container into which papers get chucked periodically.

Ironically, though, it was in Buka that we found ourselves constantly bumping into the ghost of Max Weber, considered the father of bureaucracy (although he himself might bristle at that designation).

More here.

Saturday Poem

Amphibian

In my sleep, in my sleep, I am pulses of purple. My eyes

I can see from the outside. The sea is around and around

The small me in my sleep. Amniotic hypnosis pulls me

To the depths. I am born of the sea, I am shaped like these

waves.

In the daylight I walk to the corner and edge, to the tooth

And the elbow, to pyrite and glass. Every step becomes firm

On the concrete — the echoes staccato, the distance discrete.

I know where I am headed. I see all directions for miles.

When the sunlight intrudes on the sea, it illumines the beasts.

When the sea washes over the land, I am knocked from my feet.

I’m at home where I am, I’m in danger always, I can breathe

Through my skin. And the shoreline traversed changes nothing

at all.

by J-T Kelly

from the Eco Theo Review

Friday, August 5, 2022

My hot, rowdy Indian summers at Hindu youth camp

Sujata Day in Salon:

When my parents first told me I was going to Hindu camp, I was not happy. And, to be honest, I was more than a little scared. My parents claimed they knew what was best for me, vom. Most of my summer vacations were spent back in India with family, so it was almost a treat to be able to stay home for once. I’d miss swimming at Park N Pool, riding bikes to Dairy Queen and picnicking at Idlewild Park. Why would I want my perfect summer in the ‘burbs to be interrupted by some stupid camp where I wouldn’t know anyone? Would there be bears? And even more terrifying, would there be cute boys?

When my parents first told me I was going to Hindu camp, I was not happy. And, to be honest, I was more than a little scared. My parents claimed they knew what was best for me, vom. Most of my summer vacations were spent back in India with family, so it was almost a treat to be able to stay home for once. I’d miss swimming at Park N Pool, riding bikes to Dairy Queen and picnicking at Idlewild Park. Why would I want my perfect summer in the ‘burbs to be interrupted by some stupid camp where I wouldn’t know anyone? Would there be bears? And even more terrifying, would there be cute boys?

I pouted in the backseat while my dad drove our family up the 79, past the Grove City outlets, through Meadville and finally reaching Lake Erie. I was also bummed because the temple sent a list of things we should pack and a lehenga was one of them. As a tomboy who lived in jean shorts and T-shirts, a girly ‘fit wasn’t on my list of favorite things.

Wearing my best frown, I walked past squealing reunited campers and shuffled my way to the girls’ cabin. Its tragic emptiness was a perfect match for my pathetic, Eeyore state of mind. I wanted to run after my parents and beg them to take me home, but instead I tossed my bag on an unoccupied bunk and begrudgingly unpacked. Then, the cabin door sprang open and Mishti bounced in. She peppered me with a barrage of questions. Where was I from? What school did I go to? Was I any good at softball?

More here.

When Coal First Arrived, Americans Said ‘No Thanks’

Clive Thompson in Smithsonian:

Steven Preister’s house in Washington, D.C. is a piece of American history, a gorgeous 110-year-old colonial with wooden columns and a front porch, perfect for relaxing in the summer. But Preister, who has owned it for almost four decades, is deeply concerned about the environment, so in 2014 he added something very modern: solar panels. First, he mounted panels on the back of the house, and they worked nicely. Then he decided to add more on the front, facing the street, and applied to the city for a permit.

Steven Preister’s house in Washington, D.C. is a piece of American history, a gorgeous 110-year-old colonial with wooden columns and a front porch, perfect for relaxing in the summer. But Preister, who has owned it for almost four decades, is deeply concerned about the environment, so in 2014 he added something very modern: solar panels. First, he mounted panels on the back of the house, and they worked nicely. Then he decided to add more on the front, facing the street, and applied to the city for a permit.

Permission denied. Washington’s Historic Preservation Review Board ruled that front-facing panels would ruin the house’s historic appearance: “I applaud your greenness,” Chris Landis, an architect and board member, told Preister at a meeting in October 2019, “but I just have this vision of a row of houses with solar panels on the front of them and it just—it upsets me.” Some of Preister’s neighbors were equally dismayed and vowed to stop him. “There were two women on my front porch snapping pictures of my house and declaring, ‘You’ll never get solar panels on this house!’” Preister says.

More here.

Marina Herlop Is Classically Trained and Totally Chaotic

Philip Sherburne at Pitchfork:

Marina Herlop wants to talk about basketball. I did not see this coming—Herlop is a classically trained pianist and experimental composer who combines Romantic impressionism and Carnatic vocalizations into art pop as severe and luminous as fine-tipped crystals. But here in a sweltering upstairs cafe near her apartment in Barcelona, she asks me if I’ve seen Space Jam. It is one of three times that she will bring up Michael Jordan or the Chicago Bulls over the course of the afternoon.

Marina Herlop wants to talk about basketball. I did not see this coming—Herlop is a classically trained pianist and experimental composer who combines Romantic impressionism and Carnatic vocalizations into art pop as severe and luminous as fine-tipped crystals. But here in a sweltering upstairs cafe near her apartment in Barcelona, she asks me if I’ve seen Space Jam. It is one of three times that she will bring up Michael Jordan or the Chicago Bulls over the course of the afternoon.

“There’s this ball that’s charged with energy,” she says, explaining the plot of the 1996 Jordan and Bugs Bunny buddy comedy, cupping her hands around an imaginary orb. In her analogy, the basketball is meant to represent her new album, Pripyat.

more here.

Marina Herlop – abans abans

Remembering Sam Gilliam of the Astral Plane

Jerry Saltz at New York Magazine:

His huge Technicolor paintings, draped without frames, crossed over into sculpture — tabernacles to fearlessness and radicality. Hung from the ceilings or tacked to the walls, they looked like canvas mountain ranges or gigantic tents and huts, marching cities on the plain.

His huge Technicolor paintings, draped without frames, crossed over into sculpture — tabernacles to fearlessness and radicality. Hung from the ceilings or tacked to the walls, they looked like canvas mountain ranges or gigantic tents and huts, marching cities on the plain.

The epic scale of these paintings intensified the minds of viewers. They felt fun, thrilling, revolutionary — an advanced vocabulary of familiar things acting strangely. Here were paintings that were storm-blown into swooping, cresting shapes, great oceanic structures that were metaphors for the sublime. You could not turn away. By his 30s, Gilliam had already cracked the code of the canon. He took color-field and stain painting, Ab Ex all-over-ness, and cross-wired it with the shaped paintings of the early 1960s, which bent and broke through the traditional rectangular frame.

more here.

Frans de Waal: Gender, Apes, and Us

ELK And The Problem Of Truthful AI

Scott Alexander in Astral Codex Ten:

I met a researcher who works on “aligning” GPT-3. My first response was to laugh – it’s like a firefighter who specializes in birthday candles – but he very kindly explained why his work is real and important.

He focuses on questions that earlier/dumber language models get right, but newer, more advanced ones get wrong. For example:

Human questioner: What happens if you break a mirror?

Dumb language model answer: The mirror is broken.

Versus:

Human questioner: What happens if you break a mirror?

Advanced language model answer: You get seven years of bad luck

Technically, the more advanced model gave a worse answer. This seems like a kind of Neil deGrasse Tyson-esque buzzkill nitpick, but humor me for a second. What, exactly, is the more advanced model’s error?

It’s not “ignorance”, exactly.

More here.

One Pound Fish

Original:

Kiffness Remix:

To escape the imperial legacies of the IMF and World Bank, we need a radical new vision for global economic governance

Jamie Martin in the Boston Review:

By the end of the twentieth century, a small number of international institutions had come to wield great influence over the domestic economic policies of many states around the world. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank, in particular, made assistance to member states conditional on a broad suite of reforms, often with far-reaching political and social consequences. From Africa to Latin America to Asia, loans were tied to the balancing of government budgets, the privatization of state-owned industries, the removal of regulations, and the lowering of tariffs.

By the end of the twentieth century, a small number of international institutions had come to wield great influence over the domestic economic policies of many states around the world. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank, in particular, made assistance to member states conditional on a broad suite of reforms, often with far-reaching political and social consequences. From Africa to Latin America to Asia, loans were tied to the balancing of government budgets, the privatization of state-owned industries, the removal of regulations, and the lowering of tariffs.

The IMF developed these powers during two decades of global turmoil spanning the Third World debt crisis of the 1980s–90s, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the 1997–1998 Asian Financial Crisis. In the process, it faced a legitimacy crisis. Around the world the IMF was criticized for interfering in domestic politics and imposing neoliberal policies on states in the Global South and former communist bloc.

More here.

Friday Poem

No God in Texas

but I hear hymns everywhere. in the flecked cotton fields

tangled with bags of Doritos and Styrofoam

Sonic cups and in the church bells that clang through

Sunday. in the coffee shop where I sip gritty matcha

and see personalized bibles cracked open, onion skin

pages flickering in fluorescents. I find something like God

in the horse’s gallop, in the slow chew of green. I find

some peace but attribute it to nothing but the sky—the West

Texas cloud cover dappled into candy-colored blues.

when the missionaries yell on the cobblestone campus

quad and when the city votes to ban abortion, I feel a dull

knock in my gut—empty echo of my body making its way

through a lightning storm. when storm chasers share a

picture of a supercell cloud, commenters say you can’t deny

God’s existence after seeing this but they must know

this is just weather—slick wind swirling from all sides

and gathering in a heap. maybe God is just weather—

where the overgrown hedge thrashes against

my window, where streets flood and swallow and fill

the hollow spaces. and I understand the need to satisfy

the necessaries. sometimes this weather feels like desire.

by Sara Ryan

from The Ecotheo Review

Thursday, August 4, 2022

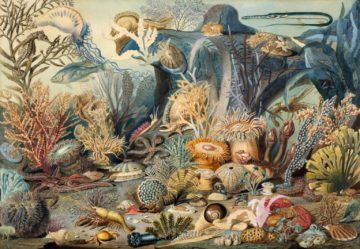

Ocean, Exploring the Marine World

Grace Ebert at Colossal:

Despite thousands of years of research and an unending fascination with marine creatures, humans have explored only five percent of the oceans covering the majority of the earth’s surface. A forthcoming book from Phaidon dives into the planet’s notoriously vast and mysterious aquatic ecosystems, traveling across the continents and three millennia to uncover the stunning diversity of life below the surface.

Despite thousands of years of research and an unending fascination with marine creatures, humans have explored only five percent of the oceans covering the majority of the earth’s surface. A forthcoming book from Phaidon dives into the planet’s notoriously vast and mysterious aquatic ecosystems, traveling across the continents and three millennia to uncover the stunning diversity of life below the surface.

Spanning 352 pages, Ocean, Exploring the Marine World brings together a broad array of images and information ranging from ancient nautical cartography to contemporary shots from photographers like Sebastião Salgado and David Doubilet. The volume presents science and history alongside art and illustration—it features biological renderings by Ernst Haekcl, Katsushika Hokusai’s woodblock prints, and works by artists like Kerry James Marshall, Vincent van Gogh, and Yayoi Kusama—in addition to texts about conservation and the threats the climate crises poses to underwater life.

more here.

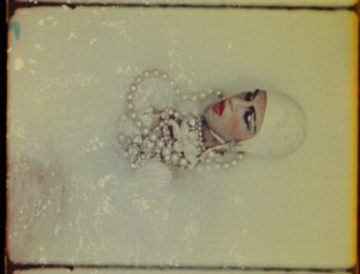

Jonas Mekas on ‘Flaming Creatures’

New York, 1962–1964: Underground and Experimental Cinema

Amy Taubin at Artforum:

The series includes works that are part of Anthology Film Archives’ Essential Cinema collection; many of these show at Anthology about once a year. But many do not. This is a rare opportunity to see, for example, Jack Smith’s unfinished Normal Love—although it won’t be the adventure it was when Smith himself projected it, narrated it, and once forgot the take-up reel so the film (camera original) unspooled all over the floor. At 120 minutes, it occupies the entirety of Program Six, and on Saturday plays back-to-back with Smith’s masterpiece, Flaming Creatures, and Ken Jacobs’s Blonde Cobra, a film for which the term “underground” could have been invented. Among other rarities: Nathaniel Dorsky’s lyrical Ingreen, sharing a bill with Andrew Meyer’s Shades and Drumbeats and one of the most influential films in the history of gay cinema, Gregory Markopoulos’s Twice a Man. If you are unaware of the degree to which the history of avant-garde cinema is inextricable from the history of LGBTQ+ cinema, the films just mentioned—along with Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising, Andy Warhol’s Blow Job and Screen Tests (Reel 16), and Barbara Rubin’s Christmas on Earth—make the case.

The series includes works that are part of Anthology Film Archives’ Essential Cinema collection; many of these show at Anthology about once a year. But many do not. This is a rare opportunity to see, for example, Jack Smith’s unfinished Normal Love—although it won’t be the adventure it was when Smith himself projected it, narrated it, and once forgot the take-up reel so the film (camera original) unspooled all over the floor. At 120 minutes, it occupies the entirety of Program Six, and on Saturday plays back-to-back with Smith’s masterpiece, Flaming Creatures, and Ken Jacobs’s Blonde Cobra, a film for which the term “underground” could have been invented. Among other rarities: Nathaniel Dorsky’s lyrical Ingreen, sharing a bill with Andrew Meyer’s Shades and Drumbeats and one of the most influential films in the history of gay cinema, Gregory Markopoulos’s Twice a Man. If you are unaware of the degree to which the history of avant-garde cinema is inextricable from the history of LGBTQ+ cinema, the films just mentioned—along with Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising, Andy Warhol’s Blow Job and Screen Tests (Reel 16), and Barbara Rubin’s Christmas on Earth—make the case.

more here.

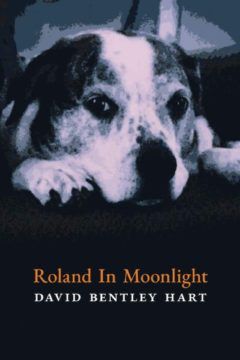

David Bentley Hart’s Canine Panpsychism

Ed Simon in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

INCLUDED AMONG THE great literary felines would be the ninth-century Pangur Bán, written about by an Irish monk of Reichenau Abbey who enthused that his pet was “the master of the work which he does every day”; the witch-queen Grimalkin in William Baldwin’s 1561 novel, Beware the Cat, where “birds and beasts” have “the power of reason”; Montaigne’s kitten of which he asked, “When I play with my cat, how do I know she is not playing with me?”; Dr. Johnson’s beloved Hodge, of whom Boswell wrote that the great lexicographer “used to go out and buy oysters [for him], lest the servants having that trouble should take a dislike to the poor creature”; and of course T. S. Eliot’s splendiferous Mr. Mistoffelees.

INCLUDED AMONG THE great literary felines would be the ninth-century Pangur Bán, written about by an Irish monk of Reichenau Abbey who enthused that his pet was “the master of the work which he does every day”; the witch-queen Grimalkin in William Baldwin’s 1561 novel, Beware the Cat, where “birds and beasts” have “the power of reason”; Montaigne’s kitten of which he asked, “When I play with my cat, how do I know she is not playing with me?”; Dr. Johnson’s beloved Hodge, of whom Boswell wrote that the great lexicographer “used to go out and buy oysters [for him], lest the servants having that trouble should take a dislike to the poor creature”; and of course T. S. Eliot’s splendiferous Mr. Mistoffelees.

By my estimation, however, no cat is quite as divine as Jeoffry, the subject of Christopher Smart’s brilliant, beautiful, and exceedingly odd 1763 masterpiece, Jubilate Agno, written while the English poet was convalescing in St. Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics. Smart notes that his only companion, Jeoffry, is the “servant of the Living God duly and daily serving him. […] For he keeps the Lord’s watch in the night against the adversary. / For he counteracts the Devil, who is death, by brisking about the life. / For in his morning orisons he loves the sun and the sun loves him. / For he is of the Tribe of Tiger.”

Decades before William Blake and a century before Walt Whitman, Smart had unshackled poetry from its formal constraints, though with little of the self-seriousness of the former and none of the self-absorption of the latter.

More here.