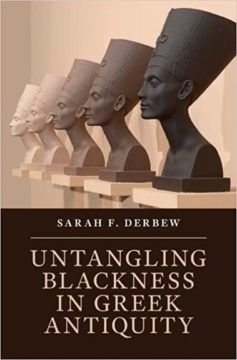

Najee Olya at the LARB:

Derbew’s book arrives at a pivotal moment in classical studies. The past years have seen debates on the whiteness of the discipline and calls to burn the field down. The very term “classics” has come under fire for its perceived elitism and opacity, with eminent departments (including Berkeley’s) abandoning the name. Some have criticized the field’s intense focus on ancient Greek and Latin at the expense of archaeology, the ancient Mediterranean outside Greece and Rome, and the interdisciplinarity that forms the foundation of research like Derbew’s. Perhaps unsurprisingly, attempts to broaden the boundaries of the discipline have drawn fire from some quarters. The recent reworking of Princeton’s undergraduate language requirements in classics, for example, has become grist for the culture warrior’s mill. Yet what Sarah Derbew has accomplished is a testament to the kind of innovative work one can do by combining traditional philological rigor with fresh and novel thinking.

Derbew’s book arrives at a pivotal moment in classical studies. The past years have seen debates on the whiteness of the discipline and calls to burn the field down. The very term “classics” has come under fire for its perceived elitism and opacity, with eminent departments (including Berkeley’s) abandoning the name. Some have criticized the field’s intense focus on ancient Greek and Latin at the expense of archaeology, the ancient Mediterranean outside Greece and Rome, and the interdisciplinarity that forms the foundation of research like Derbew’s. Perhaps unsurprisingly, attempts to broaden the boundaries of the discipline have drawn fire from some quarters. The recent reworking of Princeton’s undergraduate language requirements in classics, for example, has become grist for the culture warrior’s mill. Yet what Sarah Derbew has accomplished is a testament to the kind of innovative work one can do by combining traditional philological rigor with fresh and novel thinking.

more here.

Humans, frogs and many other widely studied animals start as a single cell that immediately divides again and again into separate cells. In crickets and most other insects, initially just the cell nucleus divides, forming many nuclei that travel throughout the shared cytoplasm and only later form cellular membranes of their own. In 2019, Stefano Di Talia, a quantitative developmental biologist at Duke University,

Humans, frogs and many other widely studied animals start as a single cell that immediately divides again and again into separate cells. In crickets and most other insects, initially just the cell nucleus divides, forming many nuclei that travel throughout the shared cytoplasm and only later form cellular membranes of their own. In 2019, Stefano Di Talia, a quantitative developmental biologist at Duke University,  Some, including me, may be suffering from Chronic Password Fatigue Syndrome (CPFS would be the acronym). Scientific publishing, peer review and paywalls are a very problematic area that contributes to disparities around the world, among other

Some, including me, may be suffering from Chronic Password Fatigue Syndrome (CPFS would be the acronym). Scientific publishing, peer review and paywalls are a very problematic area that contributes to disparities around the world, among other  On April 3, 1911, Edna St. Vincent Millay took her first lover. She was 19 years old, and she engaged herself to this man with a ring that “came to me in a fortune-cake” and was “the symbol of all earthly happiness.” Millay had just graduated from high school and had taken charge of running the household while her mother worked as a traveling nurse. She fixed her younger sisters dinner, washed and mended all their clothes, and entertained their guests. Her lover had no name and no body; he was a figment she’d conjured up to help her get through the stress and loneliness of being a teenage caretaker. This first lover, her “shadow,” is not often recounted among the many others she later had, but Millay had various ways of making these exhausting days of her early adulthood endlessly charming and alive. In one note to her lover, she describes the chafing dish she served her siblings’ dinner on, which she called James, and jokes, “Why don’t you come over some evening and have something on ‘James’—doesn’t that sound dreadful—‘have something on James’!”

On April 3, 1911, Edna St. Vincent Millay took her first lover. She was 19 years old, and she engaged herself to this man with a ring that “came to me in a fortune-cake” and was “the symbol of all earthly happiness.” Millay had just graduated from high school and had taken charge of running the household while her mother worked as a traveling nurse. She fixed her younger sisters dinner, washed and mended all their clothes, and entertained their guests. Her lover had no name and no body; he was a figment she’d conjured up to help her get through the stress and loneliness of being a teenage caretaker. This first lover, her “shadow,” is not often recounted among the many others she later had, but Millay had various ways of making these exhausting days of her early adulthood endlessly charming and alive. In one note to her lover, she describes the chafing dish she served her siblings’ dinner on, which she called James, and jokes, “Why don’t you come over some evening and have something on ‘James’—doesn’t that sound dreadful—‘have something on James’!” In the U.S., public health agencies generally don’t test sewage for polio. Instead, they wait for people to show up sick in doctor’s offices or hospitals — a reactive strategy that can give this stealthy virus more time to circulate silently through the community before it is detected.

In the U.S., public health agencies generally don’t test sewage for polio. Instead, they wait for people to show up sick in doctor’s offices or hospitals — a reactive strategy that can give this stealthy virus more time to circulate silently through the community before it is detected. Many people have recognized the centrality of polarization and offered solutions for how to get out of it. Among these are: institutional changes, especially to our electoral laws, that would restructure the incentives under which politicians operate; the growth of a third, centrist party that grabs the middle ground from the extreme wings of the existing two; and grassroots movements to build moderation and understanding from the bottom up. All of these will be important components of depolarization, but none of them will be sufficient by themselves or take place soon enough to solve the problem.

Many people have recognized the centrality of polarization and offered solutions for how to get out of it. Among these are: institutional changes, especially to our electoral laws, that would restructure the incentives under which politicians operate; the growth of a third, centrist party that grabs the middle ground from the extreme wings of the existing two; and grassroots movements to build moderation and understanding from the bottom up. All of these will be important components of depolarization, but none of them will be sufficient by themselves or take place soon enough to solve the problem. I have worked in restaurants, lived on sustenance homesteads, volunteered for aquaponics and permaculture farms, and harvested at food forests from Hawaii to Texas. I invariably come home with a crate of spare cuttings and leftovers that no one else wants. My pockets are often full of uneaten complimentary bread.

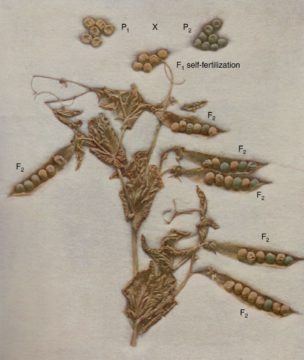

I have worked in restaurants, lived on sustenance homesteads, volunteered for aquaponics and permaculture farms, and harvested at food forests from Hawaii to Texas. I invariably come home with a crate of spare cuttings and leftovers that no one else wants. My pockets are often full of uneaten complimentary bread. There are few historical records concerning Gregor Johann Mendel and his work, so theories abound concerning his motivation. These theories range from Fisher’s view that Mendel was testing a fully formed previous theory of inheritance to Olby’s view that Mendel was not interested in inheritance at all, whereas textbooks often state his motivation was to understand inheritance. In this Perspective, we review current ideas about how Mendel arrived at his discoveries and then discuss an alternative scenario based on recently discovered historical sources that support the suggestion that Mendel’s fundamental research on the inheritance of traits emerged from an applied plant breeding program. Mendel recognized the importance of the new cell theory; understanding of the formation of reproductive cells and the process of fertilization explained his segregation ratios. This interest was probably encouraged by his friendship with Johann Nave, whose untimely death preceded Mendel’s first 1865 lecture by a few months. This year is the 200th anniversary of Mendel’s birth, presenting a timely opportunity to revisit the events in his life that led him to undertake his seminal research. We review existing ideas on how Mendel made his discoveries, before presenting more recent evidence.

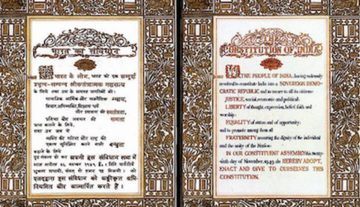

There are few historical records concerning Gregor Johann Mendel and his work, so theories abound concerning his motivation. These theories range from Fisher’s view that Mendel was testing a fully formed previous theory of inheritance to Olby’s view that Mendel was not interested in inheritance at all, whereas textbooks often state his motivation was to understand inheritance. In this Perspective, we review current ideas about how Mendel arrived at his discoveries and then discuss an alternative scenario based on recently discovered historical sources that support the suggestion that Mendel’s fundamental research on the inheritance of traits emerged from an applied plant breeding program. Mendel recognized the importance of the new cell theory; understanding of the formation of reproductive cells and the process of fertilization explained his segregation ratios. This interest was probably encouraged by his friendship with Johann Nave, whose untimely death preceded Mendel’s first 1865 lecture by a few months. This year is the 200th anniversary of Mendel’s birth, presenting a timely opportunity to revisit the events in his life that led him to undertake his seminal research. We review existing ideas on how Mendel made his discoveries, before presenting more recent evidence. AS SOMEONE WHO grew up in India in the early 2000s, after the once-colonized country had opened itself to the global economy, one thing was clear to me. Aspiration and English were synonymous. Both were essential. This lesson was drilled into me at my missionary-run English-medium high school in New Delhi. Whether we dreamed of becoming doctors or engineers or corporate hotshots, we were repeatedly told that we needed to have English. Students were penalized for speaking in any language other than English, and our pronunciations were disciplined in preparation for roles no one doubted we would take on. Away from the institutional ear, my peers and I still cherished our other languages, to varying degrees. But, for the most part, we learned to joke, dream, rebel, and obey in English.

AS SOMEONE WHO grew up in India in the early 2000s, after the once-colonized country had opened itself to the global economy, one thing was clear to me. Aspiration and English were synonymous. Both were essential. This lesson was drilled into me at my missionary-run English-medium high school in New Delhi. Whether we dreamed of becoming doctors or engineers or corporate hotshots, we were repeatedly told that we needed to have English. Students were penalized for speaking in any language other than English, and our pronunciations were disciplined in preparation for roles no one doubted we would take on. Away from the institutional ear, my peers and I still cherished our other languages, to varying degrees. But, for the most part, we learned to joke, dream, rebel, and obey in English. In the late afternoon of September 21, 2018, I exited my New York apartment building carrying a folding table and a big sign reading GRAMMAR TABLE. I crossed Broadway to a little park called Verdi Square, found a spot at the northern entrance to the Seventy-Second Street subway station, propped up my sign, and prepared to answer grammar questions from passersby.

In the late afternoon of September 21, 2018, I exited my New York apartment building carrying a folding table and a big sign reading GRAMMAR TABLE. I crossed Broadway to a little park called Verdi Square, found a spot at the northern entrance to the Seventy-Second Street subway station, propped up my sign, and prepared to answer grammar questions from passersby. INTERPRETING ANCIENT DNA

INTERPRETING ANCIENT DNA I remember all too well that day early in the pandemic when we first received the “stay at home” order. My attitude quickly shifted from feeling like I got a “snow day” to feeling like a bird in a cage. Being a person who is both extraverted by nature and not one who enjoys being told what to do, the transition was pretty rough.

I remember all too well that day early in the pandemic when we first received the “stay at home” order. My attitude quickly shifted from feeling like I got a “snow day” to feeling like a bird in a cage. Being a person who is both extraverted by nature and not one who enjoys being told what to do, the transition was pretty rough. “O

“O An injectable drug that protects people at high risk of HIV infection has been recommended for use by the World Health Organization (WHO). Cabotegravir (also known as CAB-LA), which is given every two months, was initially approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in December 2021.

An injectable drug that protects people at high risk of HIV infection has been recommended for use by the World Health Organization (WHO). Cabotegravir (also known as CAB-LA), which is given every two months, was initially approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in December 2021. Care work — tending to the sick, the very young or the very old — has long been denied the kind of recognition (and remuneration) that

Care work — tending to the sick, the very young or the very old — has long been denied the kind of recognition (and remuneration) that