Odd Lots interviews Jon Turek:

Category: Recommended Reading

Anti-Liberal

Terry Eagleton in Sidecar [h/t: Leonard Benardo]:

Terry Eagleton in Sidecar [h/t: Leonard Benardo]:

A well-known member of the British left once discovered to his surprise that several of his socialist friends, including myself, had all attended the same school. We weren’t, however, public schoolboys in flight from our privileged backgrounds; nor was the school the kind of place where you call the teachers Nick and Maggie and are encouraged to have sex on the floor of the assembly hall. It was a Roman Catholic grammar school in Manchester, run by an obscure order of clerics, and like most Catholic schools in Britain its pupils were almost all descendants of Irish working-class immigrants.

There have been a number of prominent Catholics on the British left, most of them what the church would call ‘lapsed’. To be lapsed is less a matter of ceasing to be a Catholic than a particular way of being one – a fairly honorific way, in fact, which includes such luminaries as Graham Greene and Seamus Heaney. The result is that nobody can ever leave the Catholic church; instead, they are simply shuttled from one category to another, rather as a retired Brigadier is still a Brigadier. The political philosopher Raymond Geuss confesses in his latest book, Not Thinking like a Liberal, that his religious upbringing failed to make him even a bad Catholic; yet bad Catholics are what the lapsed really are, often productively so. They can be heretics in the truth, to use John Milton’s phrase. Geuss may not go along with the church on such minor matters as the existence of God, but he insists that none of his fundamental attitudes have changes since his schooldays, which the clerics who taught him would no doubt be delighted to hear. As a staunch anti-liberal, he remains a bad Catholic to the end.

More here.

Humans Know a Lot, This Author Concedes, and Most of It Is Useless

Jennifer Szalai in The New York Times:

Gregg studies animal behavior and is an expert in dolphin communication. He shows how human cognition is extraordinarily complex, allowing us to paint pictures and write symphonies. We can share ideas with one another so that we don’t have to rely only on gut instinct or direct experience in order to learn. But this compulsion to learn can be superfluous, he says. We accumulate what the philosopher Ruth Garrett Millikan calls “dead facts” — knowledge about the world that is useless for daily living, like the distance to the moon, or what happened in the latest episode of “Succession.” Our collections of dead facts, Gregg writes, “help us to imagine an infinite number of solutions to whatever problems we encounter — for good or ill.”

Gregg studies animal behavior and is an expert in dolphin communication. He shows how human cognition is extraordinarily complex, allowing us to paint pictures and write symphonies. We can share ideas with one another so that we don’t have to rely only on gut instinct or direct experience in order to learn. But this compulsion to learn can be superfluous, he says. We accumulate what the philosopher Ruth Garrett Millikan calls “dead facts” — knowledge about the world that is useless for daily living, like the distance to the moon, or what happened in the latest episode of “Succession.” Our collections of dead facts, Gregg writes, “help us to imagine an infinite number of solutions to whatever problems we encounter — for good or ill.”

“If Nietzsche Were a Narwhal” is mostly fixated on the ill, or the way that humans insist they are improving things when they are ultimately mucking them up. There is already a stuffed shelf of books about how we aren’t as smart as we like to think we are, or how our smartness can lead us astray: David Robson’s “The Intelligence Trap,” Leonard Mlodinow’s “Emotional,” books in behavioral economics by Daniel Kahneman or Dan Ariely. But Gregg makes a bigger case about how human intelligence has deformed the planet as well. He explicitly ventures into the conflict between optimists like Steven Pinker and pessimists like the British philosopher John Gray.

More here.

Republicans went crazy over the Trump search. Now they look idiotic

Max Boot in The Washington Post:

The more we learn about the FBI’s search of Mar-a-Lago, the sillier — and more sinister — the overcaffeinated Republican defenses of former president Donald Trump look. A genius-level spinmeister, Trump set the tone with a Monday evening statement announcing: “These are dark times for our Nation, as my beautiful home, Mar-A-Lago in Palm Beach, Florida, is currently under siege, raided, and occupied by a large group of FBI agents. Nothing like this has ever happened to a President of the United States before.” That description allowed his followers to imagine a scene straight out of a Hollywood action picture, with agents in FBI jackets busting down the doors and holding the former president and first lady at gunpoint while they ransacked the premises. Although Trump’s team had a copy of the search warrant, he gave no hint of why the FBI might have been there, claiming, “It is … an attack by Radical Left Democrats who desperately don’t want me to run for President in 2024.”

The more we learn about the FBI’s search of Mar-a-Lago, the sillier — and more sinister — the overcaffeinated Republican defenses of former president Donald Trump look. A genius-level spinmeister, Trump set the tone with a Monday evening statement announcing: “These are dark times for our Nation, as my beautiful home, Mar-A-Lago in Palm Beach, Florida, is currently under siege, raided, and occupied by a large group of FBI agents. Nothing like this has ever happened to a President of the United States before.” That description allowed his followers to imagine a scene straight out of a Hollywood action picture, with agents in FBI jackets busting down the doors and holding the former president and first lady at gunpoint while they ransacked the premises. Although Trump’s team had a copy of the search warrant, he gave no hint of why the FBI might have been there, claiming, “It is … an attack by Radical Left Democrats who desperately don’t want me to run for President in 2024.”

His followers — which means pretty much the whole of the Republican Party — took up the cry based on no more information than that. Fox News host Mark Levin called the search “the worst attack on this republic in modern history, period.” Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Tex.) called it “corrupt & an abuse of power.” Sen. Rick Scott (R-Fla.) compared the FBI to “the Gestapo.” Not to be outdone, former House speaker Newt Gingrich (R-Whackadoodle) said the FBI was the “American Stasi,” and compared its agents to wolves “who want to eat you.” “Today is war,” declared Steven Crowder, a podcaster with a YouTube audience of 5.6 million people. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) tweeted “DEFUND THE FBI!” Former Trump aide Stephen K. Bannon, among many others, suggested that the FBI and the Justice Department (“essentially lawless criminal organizations”) might have planted evidence.

…The New York Times, meanwhile, reported that the search was conducted by FBI agents “intentionally not wearing the blue wind breakers emblazoned with the agency’s logo usually worn during searches.” The club was closed, and Trump was not there. He was in New York, where he would plead the Fifth Amendment against self-incrimination more than 400 times during a deposition with the New York attorney general. But according to Trump’s lawyer, Trump and his family were able to watch the entire search on Mar-a-Lago’s closed-circuit security cameras. So much for the crackpot claim that the FBI could have planted evidence!

More here.

Saturday Poem

Always We Begin Again

Today you could wake up and say, It doesn’t have to be complicated—

life, that is, in the way a forest overtakes the scourge of the machine.

Eventually, the scar will be covered first by high grasses and flowering

weeds, then shoulder high pines that spine their way to the leaf ceiling.

Life, you could say, could be like that. A regrowth, something

the whole forest seems to agree upon, beginning the moment after

the metal teeth carve a wound. Life could be like that, and love.

Love—the way years from now you will look down the path

the machine took and never know that once this was the way

the humans went, blistering their way, metal teeth dripping sap.

by Aaron Brown

from the Ecotheo Review

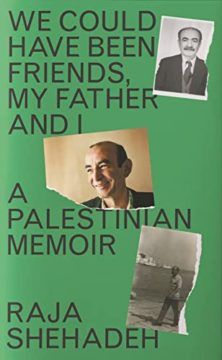

‘We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I’ by Raja Shehadeh

Ian Black at The Guardian:

Raja Shehadeh, the well-known Palestinian author, was born in 1951 in the West Bank town of Ramallah (under Jordanian rule), three years after Israel was founded. His father, Aziz, was born in Bethlehem in 1912 (then part of the Ottoman empire), five years before the Balfour declaration paved the way for the success of the Zionist movement and the Nakba – the Palestinian catastrophe caused by the creation of the Jewish state.

Raja Shehadeh, the well-known Palestinian author, was born in 1951 in the West Bank town of Ramallah (under Jordanian rule), three years after Israel was founded. His father, Aziz, was born in Bethlehem in 1912 (then part of the Ottoman empire), five years before the Balfour declaration paved the way for the success of the Zionist movement and the Nakba – the Palestinian catastrophe caused by the creation of the Jewish state.

Dates, birthplaces and governments matter a lot in this story. It is about the strained relationship between a father and his son, told by the son, against the background of one of the most intractable and divisive conflicts on earth. They were both intelligent and successful lawyers, so the account and the documentation are impressively comprehensive.

more here.

Raja Shehadeh On Britain And Palestine, A Family History

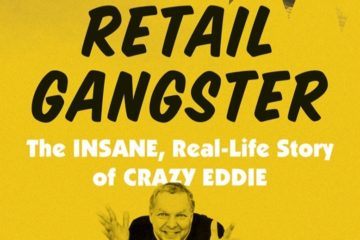

RETAIL GANGSTER: The Insane, Real-Life Story of Crazy Eddie

Alexandra Jacobs at the NYT:

The most famous TV ad in the Orwellian year of 1984, carefully themed to the novel named for this year, was for the Apple Macintosh desktop computer. The most infamous were those for Crazy Eddie, a chain of discount electronics stores in the New York metropolitan area.

The most famous TV ad in the Orwellian year of 1984, carefully themed to the novel named for this year, was for the Apple Macintosh desktop computer. The most infamous were those for Crazy Eddie, a chain of discount electronics stores in the New York metropolitan area.

Gesticulating wildly in a variety of costumes or just a gray turtleneck and a dark blazer, the actor Jerry Carroll, often mistaken for the mysterious Eddie, would rattle off a sales pitch ending with the vibrating, bug-eyed assurance: “His prices are INSANE!”

People hated those commercials, the journalist Gary Weiss reminds us in “Retail Gangster,” a compact and appealing account of Crazy Eddie’s artificially inflated rise and slow-mo collapse. But they worked — the company went public, with the inauspicious stock symbol CRZY — and also worked their way into punch lines of popular culture.

more here.

Friday, August 12, 2022

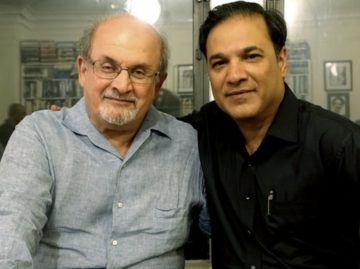

From Rushdie’s friend: “Always support free speech, especially speech we hate. Otherwise there’s no hope at all.”

Note: Salman is a closer friend of my sister Azra, but I know I also speak for her when I say that we are devastated by the terrible news we have received this evening and hope for his speedy and complete recovery.

Cynthia Haven in The Book Haven:

For most of us, Salman Rushdie is only a name in the news, a man famous for his books and his marriages. To some of my friends, including Abbas Raza, founder of 3QuarksDaily (we’ve written about it here), he is more than that. He is a personal friend, and a friend of his extended Pakistani family.

For most of us, Salman Rushdie is only a name in the news, a man famous for his books and his marriages. To some of my friends, including Abbas Raza, founder of 3QuarksDaily (we’ve written about it here), he is more than that. He is a personal friend, and a friend of his extended Pakistani family.

Hence, Karachi-born Abbas Raza wrote on Facebook today, after the attempted murder of Rushdie: “He is in critical condition with much blood loss. Apparently an artery in his neck was severed. I hope he comes back from this roaring. Let us all, in this dangerous moment, renew our commitment to always supporting free speech, especially speech we hate. Otherwise there’s no hope at all.”

More here.

The Case for Shorttermism

Robert Wright in Nonzero Newsletter:

Effective altruism—EA for short—is a pretty straightforward extension of utilitarian moral philosophy and drew much of its founding inspiration from the most famous living utilitarian philosopher, Peter Singer. The basic idea is that you should maximize the amount of increased human welfare per dollar of philanthropic donation or per hour of charitable work. A classic EA expenditure is on mosquito nets: You can actually count the lives you’re theoretically saving from the ravages of malaria and compare that with the number of lives you could have saved by, say, funding a water purification project.

Effective altruism—EA for short—is a pretty straightforward extension of utilitarian moral philosophy and drew much of its founding inspiration from the most famous living utilitarian philosopher, Peter Singer. The basic idea is that you should maximize the amount of increased human welfare per dollar of philanthropic donation or per hour of charitable work. A classic EA expenditure is on mosquito nets: You can actually count the lives you’re theoretically saving from the ravages of malaria and compare that with the number of lives you could have saved by, say, funding a water purification project.

Longtermism, by adding all generations yet unborn to the utilitarian calculus, vastly expands the horizons of effective altruists. Instead of just scanning Earth in search of people who can be efficiently helped, they can scan eternity. That may sound like a nebulous enterprise, but it has at least one clear effect that I applaud: It can get effective altruists focused on the problem of “existential threats”—things that could conceivably wipe out the whole human species.

More here.

Of Craft and Matter

Antonio Muñoz Molina at Hudson Review:

The foreground of the most looked-at painting in the museum is partly taken up by a painting seen from the back. Everything in Las Meninas seems overt and at the same time is deceptive. The mystery of what may or may not be painted on the canvas is counterpoised by the concrete evidence of its reverse, and along with it, by the irreducible material nature of the art of painting, emphasized by the scale of that enormous object made of stiff, rough cloth and wooden bars locked together firmly enough for the contraption to stand upright. Velázquez devotes as much attention to those carefully cut pieces of wood—their knots, their volume, the way the light shows them in relief, the rough texture of the cloth—as to the blond, dazzled hair of the infanta or to the butterfly, perhaps of silver filigree, that the maid María Agustina Sarmiento wears in her hair, as distinct as a piece of jewelry when seen from a distance, though it dissolves into small abstract patches of color when seen up close. Velázquez had “brushes . . . furnished with long handles,” says Palomino, “which he employed sometimes to paint from a greater distance and more boldly, so it all seemed meaningless from up close, and proved a miracle from afar.”

The foreground of the most looked-at painting in the museum is partly taken up by a painting seen from the back. Everything in Las Meninas seems overt and at the same time is deceptive. The mystery of what may or may not be painted on the canvas is counterpoised by the concrete evidence of its reverse, and along with it, by the irreducible material nature of the art of painting, emphasized by the scale of that enormous object made of stiff, rough cloth and wooden bars locked together firmly enough for the contraption to stand upright. Velázquez devotes as much attention to those carefully cut pieces of wood—their knots, their volume, the way the light shows them in relief, the rough texture of the cloth—as to the blond, dazzled hair of the infanta or to the butterfly, perhaps of silver filigree, that the maid María Agustina Sarmiento wears in her hair, as distinct as a piece of jewelry when seen from a distance, though it dissolves into small abstract patches of color when seen up close. Velázquez had “brushes . . . furnished with long handles,” says Palomino, “which he employed sometimes to paint from a greater distance and more boldly, so it all seemed meaningless from up close, and proved a miracle from afar.”

more here.

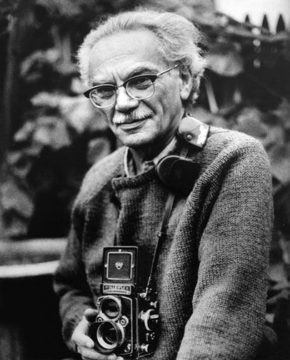

A Buffalo Photographer’s Dignified Look at the Passage of Time

Richard Brody at The New Yorker:

In the early nineties, I worked briefly as an assistant editor at Aperture, a job that involved considering unsolicited submissions of photographs. It was my good fortune that one such set of submissions was delivered to the office by the photographer himself, Milton Rogovin, and his wife, Anne, a writer and teacher. They lived in Buffalo, Anne’s home town, where Milton, a Jewish New York City native, born in 1909, was once a practicing optometrist and had long been photographing residents of his adoptive city’s relatively poor neighborhoods. The Rogovins brought a batch of his recent photos, from Buffalo’s Lower West Side, near where he had an optometry practice; some of his earlier work had been published by Aperture, and I hoped the same would happen with these newer images. It didn’t happen, but a spate of books from other publishers nonetheless followed, starting in 1994, showcasing an extraordinary body of work and with it an extraordinary couple—Milton wielded the camera, but the life project that his images embodied was a joint venture of his and Anne’s.

In the early nineties, I worked briefly as an assistant editor at Aperture, a job that involved considering unsolicited submissions of photographs. It was my good fortune that one such set of submissions was delivered to the office by the photographer himself, Milton Rogovin, and his wife, Anne, a writer and teacher. They lived in Buffalo, Anne’s home town, where Milton, a Jewish New York City native, born in 1909, was once a practicing optometrist and had long been photographing residents of his adoptive city’s relatively poor neighborhoods. The Rogovins brought a batch of his recent photos, from Buffalo’s Lower West Side, near where he had an optometry practice; some of his earlier work had been published by Aperture, and I hoped the same would happen with these newer images. It didn’t happen, but a spate of books from other publishers nonetheless followed, starting in 1994, showcasing an extraordinary body of work and with it an extraordinary couple—Milton wielded the camera, but the life project that his images embodied was a joint venture of his and Anne’s.

more here.

Milton Rogovin: The Forgotten Ones

How effective altruism went from a niche movement to a billion-dollar force

Dylan Matthews in Vox:

It’s safe to say that effective altruism is no longer the small, eclectic club of philosophers, charity researchers, and do-gooders it was just a decade ago. It’s an idea, and group of people, with roughly $26.6 billion in resources behind them, real and growing political power, and an increasing ability to noticeably change the world.

It’s safe to say that effective altruism is no longer the small, eclectic club of philosophers, charity researchers, and do-gooders it was just a decade ago. It’s an idea, and group of people, with roughly $26.6 billion in resources behind them, real and growing political power, and an increasing ability to noticeably change the world.

EA, as a subculture, has always been categorized by relentless, sometimes navel-gazing self-criticism and questioning of assumptions, so this development has prompted no small amount of internal consternation. A frequent lament in EA circles these days is that there’s just too much money, and not enough effective causes to spend it on. Bankman-Fried, who got interested in EA as an undergrad at MIT, “earned to give” through crypto trading so hard that he’s now worth about $12.8 billion as of this writing, almost all of which he has said he plans to give away to EA-aligned causes. (Disclosure: Future Perfect, which is partly supported through philanthropic giving, received a project grant from Building a Stronger Future, Bankman-Fried’s philanthropic arm.)

Along with the size of its collective bank account, EA’s priorities have also changed.

More here.

Huw Price: Risk and Reputation

Friday Poem

Origin of Violence

There is a hole.

In the hole is everything

people will do

to each other.

The hole goes down and down.

It has many rooms

like graves and like graves

they are all connected.

Roots hang from the dirt

in craggy chandeliers.

It’s not clear

where the hole stops

beginning and where

it starts to end.

It’s warm and dark down there.

The passages multiply.

There are ballrooms.

There are dead ends.

The air smells of iron and

crushed flowers.

People will do anything.

They will cut the hands off children.

Children will do anything

by Jenny George

from Smith College Poetry Center

Against the Pursuit of Happiness

Shayla Love in Vice Media:

In the last week of December 1999, a group of researchers emailed their friends, colleagues, and various listservs to ask about their plans for New Year’s Eve. They recorded how big a party a person planned to attend, how much fun they expected to have, and how much time and money they would dedicate to their festivities. This survey was not, as it may seem, an endeavor to find the most raucous and decadent New Year’s Eve party—but an attempt to capture the fleeting nature of pleasure and happiness. Of the 475 people who responded in their field study, 83 percent felt disappointed with their night. How much of a good time they expected to have, along with how much time they had spent preparing, predicted their disappointment.

In the last week of December 1999, a group of researchers emailed their friends, colleagues, and various listservs to ask about their plans for New Year’s Eve. They recorded how big a party a person planned to attend, how much fun they expected to have, and how much time and money they would dedicate to their festivities. This survey was not, as it may seem, an endeavor to find the most raucous and decadent New Year’s Eve party—but an attempt to capture the fleeting nature of pleasure and happiness. Of the 475 people who responded in their field study, 83 percent felt disappointed with their night. How much of a good time they expected to have, along with how much time they had spent preparing, predicted their disappointment.

Anyone who has looked forward to special days like birthdays, vacations, holidays, or, say, “hotvax summers,” knows these anticipated delights can be a letdown. The happiness, pleasure, and fun we expect to have doesn’t measure up to reality. This phenomenon has a name: the paradox of hedonism, or, sometimes, the paradox of happiness. It’s the strange but persistent observation that pleasure often vanishes when you try to pursue it directly. Simply put, if you try too hard at happiness, the result is unhappiness.

More here.

The big idea: are we living in a simulation?

Steven Poole in The Guardian:

Elon Musk thinks you don’t exist. But it’s nothing personal: he thinks he doesn’t exist either. At least, not in the normal sense of existing. Instead we are just immaterial software constructs running on a gigantic alien computer simulation. Musk has stated that the odds are billions to one that we are actually living in “base reality”, ie the physical universe. At the end of last year, he responded to a tweet about the anniversary of the crude tennis video game Pong (1972) by writing: “49 years later, games are photo-realistic 3D worlds. What does that trend continuing imply about our reality?”

Elon Musk thinks you don’t exist. But it’s nothing personal: he thinks he doesn’t exist either. At least, not in the normal sense of existing. Instead we are just immaterial software constructs running on a gigantic alien computer simulation. Musk has stated that the odds are billions to one that we are actually living in “base reality”, ie the physical universe. At the end of last year, he responded to a tweet about the anniversary of the crude tennis video game Pong (1972) by writing: “49 years later, games are photo-realistic 3D worlds. What does that trend continuing imply about our reality?”

This idea is surprisingly popular among philosophers and even some scientists. Its modern version is based on a seminal 2003 paper, Are We Living in a Computer Simulation? by the Swedish philosopher Nick Bostrom. Assume, he says, that in the far future, civilisations hugely more technically advanced than ours will be interested in running “ancestor simulations” of the sentient beings in their distant galactic past. If so, there will one day be many more simulated minds than real minds. Therefore you should be very surprised if you are actually one of the few real minds in existence rather than one of the trillions of simulated minds.

More here.

Thursday, August 11, 2022

Deleuze, Kierkegaard and the Ethics of Selfhood

Henry Somers-Hall at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews:

While there are references to Kierkegaard scattered through Gilles Louis René Deleuze’s work, these references have largely been overshadowed by the more pronounced (and less overtly ambivalent) influence of Nietzsche on Deleuze’s thought. For both, opposition to Hegel is a central theme in their thought, which for both leads to an attempt as Deleuze writes, ‘to escape the element of reflection’ (Deleuze 1994: 8). Similarly, both emphasise the importance of philosophical style, and move to indirect communication as a way of avoiding what they see as a tendency to conflate the representation of movement or becoming with becoming itself in traditional philosophical discourse. Nonetheless, there is an obvious difference between Deleuze and Kierkegaard, with Deleuze being a thoroughgoing atheist, and Kierkegaard a major theological thinker. In this book, Andrew Jampol-Petzinger focuses on the normative dimensions of both philosophers’ work, arguing that such a reading can diffuse some of the tensions between the theological positions of the two philosophers, as well as providing a corrective to some of the readings of Deleuze’s thought that emphasise the self-destructive aspect of the Deleuzian ethical project. Jampol-Petzinger addresses this through a focus on the account of the self that both philosophers develop, one that rejects a unified model of the self in favour of an account that draws out the consequences of Kant’s fracturing of the self in his paralogisms.

While there are references to Kierkegaard scattered through Gilles Louis René Deleuze’s work, these references have largely been overshadowed by the more pronounced (and less overtly ambivalent) influence of Nietzsche on Deleuze’s thought. For both, opposition to Hegel is a central theme in their thought, which for both leads to an attempt as Deleuze writes, ‘to escape the element of reflection’ (Deleuze 1994: 8). Similarly, both emphasise the importance of philosophical style, and move to indirect communication as a way of avoiding what they see as a tendency to conflate the representation of movement or becoming with becoming itself in traditional philosophical discourse. Nonetheless, there is an obvious difference between Deleuze and Kierkegaard, with Deleuze being a thoroughgoing atheist, and Kierkegaard a major theological thinker. In this book, Andrew Jampol-Petzinger focuses on the normative dimensions of both philosophers’ work, arguing that such a reading can diffuse some of the tensions between the theological positions of the two philosophers, as well as providing a corrective to some of the readings of Deleuze’s thought that emphasise the self-destructive aspect of the Deleuzian ethical project. Jampol-Petzinger addresses this through a focus on the account of the self that both philosophers develop, one that rejects a unified model of the self in favour of an account that draws out the consequences of Kant’s fracturing of the self in his paralogisms.

more here.

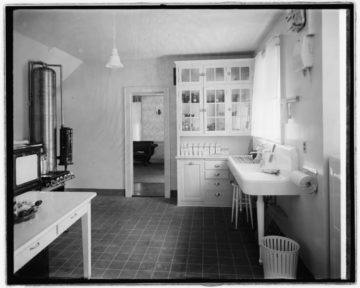

The Choreography Of Chicken Soup

Editors at The Paris Review:

The seventies and eighties were a high point in American dance, and consequently, dance on television. As video technologies advanced, one-off performances inaccessible to most could be seamlessly captured and broadcast to the masses. Like all art forms, dance at this time was also influenced aesthetically by this new medium, as cinematic techniques permeated the choreographic (and vice versa). Today, many of these dance films are archived on YouTube. My favorite is a recording of avant-garde choreographer Blondell Cummings’s Chicken Soup, a one-woman monologue in dance that aired in 1988 on a TV program called Alive from Off Center. The piece is set to a minimalist score Cummings composed with Brian Eno and Meredith Monk. Over the music, a soft feminine voice narrates: “Coming through the open-window kitchen, all summer they drank iced coffee. With milk in it.” Cummings repeats a series of gestures: sipping coffee, threading a needle, and rocking a child. She glances with an exaggerated tilt of the head at an imaginary companion and mouths small talk—what Glenn Phillips of the Getty Museum calls her signature “facial choreography.” Her movements are sharp and distinct, creating the illusion that she is under a strobe light, or caught on slowly projected 35 mm film. She sways back and forth like a metronome, keeping time with her gestures.

The seventies and eighties were a high point in American dance, and consequently, dance on television. As video technologies advanced, one-off performances inaccessible to most could be seamlessly captured and broadcast to the masses. Like all art forms, dance at this time was also influenced aesthetically by this new medium, as cinematic techniques permeated the choreographic (and vice versa). Today, many of these dance films are archived on YouTube. My favorite is a recording of avant-garde choreographer Blondell Cummings’s Chicken Soup, a one-woman monologue in dance that aired in 1988 on a TV program called Alive from Off Center. The piece is set to a minimalist score Cummings composed with Brian Eno and Meredith Monk. Over the music, a soft feminine voice narrates: “Coming through the open-window kitchen, all summer they drank iced coffee. With milk in it.” Cummings repeats a series of gestures: sipping coffee, threading a needle, and rocking a child. She glances with an exaggerated tilt of the head at an imaginary companion and mouths small talk—what Glenn Phillips of the Getty Museum calls her signature “facial choreography.” Her movements are sharp and distinct, creating the illusion that she is under a strobe light, or caught on slowly projected 35 mm film. She sways back and forth like a metronome, keeping time with her gestures.

more here.