Category: Recommended Reading

Jean-Luc Godard (1930 – 2022) Film Director

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gwOaQ4ekuqk&ab_channel=Film%2FMusic

Javier Marías (1951 – 2022) Novelist

Are soul mates real, according to science?

Amir Levine in The Washington Post:

In other words, soul mates are made possible for us because of the way our brain is wired. What’s fascinating to me is that we are all unique. Our DNA is unique. Our faces are unique. Our brains are unique. And yet we all have the brain neurocircuitry to see another person as more special than anyone else. What happens when we make someone special like that is they become more valuable than others. There’s a lot more at stake whether they call us or don’t call us.

More here.

The Real Warriors Behind ‘The Woman King’

Meilan Solly in The Smithsonian:

At its height in the 1840s, the West African kingdom of Dahomey boasted an army so fierce that its enemies spoke of its “prodigious bravery.” This 6,000-strong force, known as the Agojie, raided villages under cover of darkness, took captives and slashed off resisters’ heads to return to their king as trophies of war. Through these actions, the Agoije established Dahomey’s preeminence over neighboring kingdoms and became known by European visitors as “Amazons” due to their similarities to the warrior women of Greek myth.

At its height in the 1840s, the West African kingdom of Dahomey boasted an army so fierce that its enemies spoke of its “prodigious bravery.” This 6,000-strong force, known as the Agojie, raided villages under cover of darkness, took captives and slashed off resisters’ heads to return to their king as trophies of war. Through these actions, the Agoije established Dahomey’s preeminence over neighboring kingdoms and became known by European visitors as “Amazons” due to their similarities to the warrior women of Greek myth.

The Woman King, a new movie starring Viola Davis as a fictionalized leader of the Agojie, tells the story of this all-woman fighting force. Directed by Gina Prince-Bythewood, the film takes place as conflict engulfs the region, and the specter of European colonization looms ominously. It represents the first time that the American film industry has dramatized the compelling story.

More here.

Saturday, September 17, 2022

Privatized Universe

Marco D’Eramo in Sidecar:

Marco D’Eramo in Sidecar:

There is no limit to human megalomania. One recent example – which went largely unnoticed during this torrid and neurotic summer – was a bizarre exchange between NASA Administrator Bill Nelson and the Chinese authorities. ‘We must be very concerned that China is landing on the Moon and saying: “It’s ours now and you stay out”’, Nelson cautioned in an interview with Die Bild. A spokesman for the Chinese Foreign Ministry immediately hit back: ‘This is not the first time for the chief of NASA to lie through his teeth and smear China’.

Nelson’s accusation was strange, given that this December will mark fifty years since anyone has set foot on our natural satellite. Since then, moon exploration has been delegated to small, tracked vehicles which scuttle over its rocky outcrops. China has only deployed one such robot, which travelled to the moon’s ‘dark side’ in 2019. So the idea that it could establish sole dominion over an area the size of Asia, suspended in a vacuum at temperatures ranging from 120 degrees Celsius during the day to minus 130 degrees at night, exposed to cosmic radiation and more than 384,000 km from the closest supply base, was somewhat of a stretch.

The accusation was all the more outlandish given that it was the US, not China, that planned to launch a gargantuan rocket into space on 29 August, completing a few lunar orbits before returning to earth, all for the modest sum of $29bn. This would be the first leg of the Artemis mission – so-called after the Greek goddess of the moon and sister of the Sun-god Apollo – which eventually aims to establish a base worth $93bn on the moon by 2025. In theory, this lunar settlement will one day serve as a launch pad for a human expedition to Mars.

More here.

Britain and the US are poor societies with some very rich people

John Burn-Murdoch in the FT (image © Bloomberg):

John Burn-Murdoch in the FT (image © Bloomberg):

Where would you rather live? A society where the rich are extraordinarily rich and the poor are very poor, or one where the rich are merely very well off but even those on the lowest incomes also enjoy a decent standard of living?

For all but the most ardent free-market libertarians, the answer would be the latter. Research has consistently shown that while most people express a desire for some distance between top and bottom, they would rather live in considerably more equal societies than they do at present. Many would even opt for the more egalitarian society if the overall pie was smaller than in a less equal one.

On this basis, it follows that one good way to evaluate which countries are better places to live than others is to ask: is life good for everyone there, or is it only good for rich people?

To find the answer, we can look at how people at different points on the income distribution compare to their peers elsewhere. If you’re a proud Brit or American, you may want to look away now.

Starting at the top of the ladder, Britons enjoy very high living standards by virtually any benchmark. Last year the top-earning 3 per cent of UK households each took home about £84,000 after tax, equivalent to $125,000 after adjusting for price differences between countries. This puts Britain’s highest earners narrowly behind the wealthiest Germans and Norwegians and comfortably among the global elite.

So what happens when we move down the rungs?

More here.

Technocracy and Crisis

Lucio Baccaro in Phenomenal World:

On September 25, Italians will be called to elect a new Parliament. The snap election follows on the heels of the collapse of the government in late July and the resignation of former European Central Bank (ECB) President Mario Draghi. That the country would dismiss such an esteemed prime minister and hold early elections—while it remains lashed by the interconnected crises of Covid-19, the rise in energy prices, and an impending recession—has been a cause of consternation and confusion for many in the international press.

From the outside, Italian politics appears mystifying and convoluted. In reality, it is quite predictable: Patterns that occurred in previous decades reemerge and repeat themselves in a cyclical manner. For the past thirty years, Italy’s perpetual state of emergency has periodically necessitated the formation of expert-led national-emergency governments. In subsequent elections, disappointed voters shift their allegiance to individuals and organizations that can credibly present themselves as an alternative to the status quo. All the while, a new existential threat on the horizon compels the remaining “responsible” forces to empower a new cohort of technocrats.

Marx warned that history repeats itself—first as tragedy, then as farce—but he never elaborated what might come next. Perhaps more germane to the Italian situation is a paraphrase of Nietzsche: Italian politics is the eternal return of the same.

More here.

Postcritique; or, The Cultural Logic of Capitalist Realism

Robert Scott in the LA Review of Books:

Robert Scott in the LA Review of Books:

“IT IS EASIER to imagine the end of the world than it is to imagine the end of capitalism.” I feel ambivalent about this familiar saying, not because I disagree with it, but because it has been overused to the point of losing its force, its ability to help us grasp the devastating reality it describes. It has, in short, become a cliché, too catchy for its own good. Irritating too is the fact that the saying is nearly always quoted with reference to its apparently disputed attribution. Who came up with it first? Fredric Jameson? Slavoj Žižek? Mark Fisher? The simple — if rather boring — answer is that Jameson was paraphrased by Žižek, and then in turn both their expressions of the idea were synthesized by Fisher into the above pithy maxim describing his concept of “capitalist realism.” According to Fisher, capitalist realism is “the widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it.” If we’re honest, the phrase’s source isn’t really a mystery. But worrying over its putatively enigmatic origins has given it the sheen of a proverb, reliable yet banal.

This trajectory from devastating truth to conventional wisdom may, however, encapsulate something essential to capitalist realism itself. It is apt, if tragically ironic, that the phrase that best describes what Robert Tally Jr. calls the “enervation of our imagination” of an alternative world (and ultimately of an alternative to the end of the world) should devolve into a stock phrase. In 1980, Christopher Ricks commented that “the feeling lately has been that we live in an unprecedented inescapability from clichés.” The maxim of capitalist realism — that “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than it is to imagine the end of capitalism” — both describes and has become an example of this depressing fact. Even the critique of capitalist realism risks being grasped by what it seeks to grasp: our seemingly ever-increasing inability to imagine something genuinely new or different, in spite of the apocalyptic threat posed by “all that exists.”

More here.

Saturday Poem

A Modified Villanelle for My Childhood

— with some help from Ahmad

I wanna write lyrical, but all I got is magical.

My book needs a poem talkin bout I remember when

Something more autobiographical

Mi familia wanted to assimilate, nothing radical,

Each month was a struggle to pay our rent

With food stamps, so dust collects on the magical.

Each month it got a little less civil

Isolation is a learned defense

When all you wanna do is write lyrical.

None of us escaped being a criminal

Of the state, institutionalized when

They found out all we had was magical.

White room is white room, it’s all statistical—

Our calendars were divided by Sundays spent

In visiting hours. Cold metal chairs deny the lyrical.

I keep my genes in the sharp light of the celestial.

My history writes itself in sheets across my veins.

My parents believed in prayer, I believed in magical

Well, at least I believed in curses, biblical

Or not, I believed in sharp fists,

Beat myself into lyrical.

But we were each born into this, anger so cosmical

Or so I thought, I wore ten chokers and a chain

Couldn’t see any significance, anger is magical.

Fists to scissors to drugs to pills to fists again

Did you know a poem can be both mythical and archeological?

I ignore the cataphysical, and I anoint my own clavicle.

by Suzi F. Garcia

from American Academy of Poets

In Our Time: Tang Era Poetry

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FS-e_Jhgsxo&ab_channel=InOurTime

‘Diaghilev’s Empire’ By Rupert Christiansen

Kathryn Hughes at The Guardian:

When young Serge Diaghilev set out to save an art form, ballet was not his first choice. The law student from the unpromising city of Perm in the Urals had started the 20th century by wanting to be a composer, until he showed his music to Rimsky-Korsakov, who was simply appalled. Then he switched to curating Russian avant-garde art, which was thrilling but had no international market. Finally, he worked his way around to ballet, which had struck him as silly when he first encountered it. Still, that was half the fun. As his friend Alexandre Benois said later: “He knew how to will a thing, he knew how to carry his will into practice.”

When young Serge Diaghilev set out to save an art form, ballet was not his first choice. The law student from the unpromising city of Perm in the Urals had started the 20th century by wanting to be a composer, until he showed his music to Rimsky-Korsakov, who was simply appalled. Then he switched to curating Russian avant-garde art, which was thrilling but had no international market. Finally, he worked his way around to ballet, which had struck him as silly when he first encountered it. Still, that was half the fun. As his friend Alexandre Benois said later: “He knew how to will a thing, he knew how to carry his will into practice.”

The will in this case involved taking an exhausted, despoiled art form and twisting it into such thrilling new shapes that the world could not help but sit up and take notice.

more here.

18th-century German Romantics: Brilliant, Petty

Jennifer Szalai at the NYT:

The grand title of Andrea Wulf’s new book is wonderfully sneaky — at least that’s how I chose to read it, considering that “Magnificent Rebels” happens to recount plenty of unmagnificent squabbling among a coterie of extremely fallible humans.

The grand title of Andrea Wulf’s new book is wonderfully sneaky — at least that’s how I chose to read it, considering that “Magnificent Rebels” happens to recount plenty of unmagnificent squabbling among a coterie of extremely fallible humans.

Wulf’s exuberant narrative spans a little more than a decade, when a group of poets and intellectuals clustered in the German university town of Jena in the last years of the 18th century and became known as the “Young Romantics.” This “Jena Set” undoubtedly saw themselves as magnificent rebels — gloriously free spirits bent on centering the self, in all of its sublime subjectivity, and throwing off the shackles of a stultifying, mechanistic order. But what gives Wulf’s book its heft and intrigue is how such lofty ideals could run aground on the stubborn persistence of petty rivalry and self-regard.

more here.

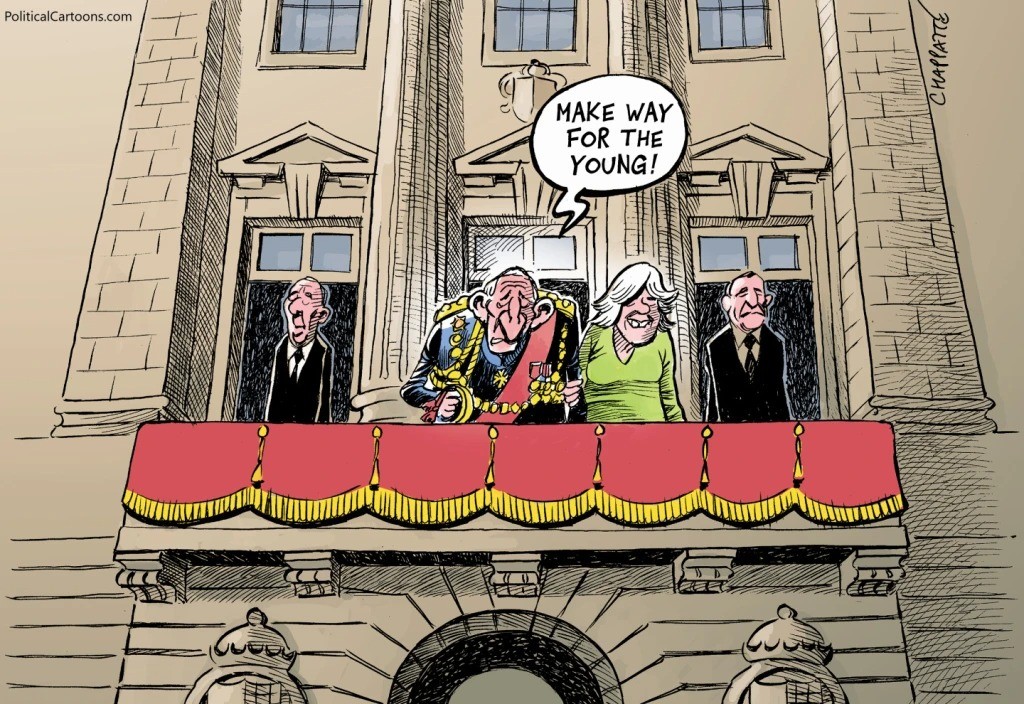

Cartoonist’s take: Sept. 11, 2022: King Charles III

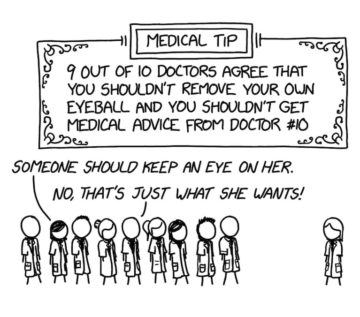

The world’s funniest former NASA roboticist will take your questions

Michael Cavna in The Washington Post:

Imagining such a hypothetical sparks the ever-curious mind of Randall Munroe, the brain behind the webcomic “xkcd” — beloved by math and science geeks the unpainted globe over — who also answers readers’ bizarre and quirky queries on his blog. His replies yielded the best-selling 2014 book “What If?: Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions.” This week, the Massachusetts-based author follows that up with the equally entertaining “What If? 2: Additional Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions,” which combines Munroe’s true research and truly funny prose with his signature stick-figure illustrations.

More here.

Friday, September 16, 2022

Is the avant-garde still avant-garde?

Stefan Collini in The Nation:

The idea of an “avant-garde” tends to inspire complex emotions, oscillating between excitement at its glamour and scorn at its pretensions. The term carries an association of being daring, experimental, unconventional; the main body of practice or opinion that it is in “advance” of is usually figured as a monolith of dull orthodoxy. But the label also easily attracts a lightly ironical coating, in which those so designated are held to be exhibiting an excess of self-consciousness or even self-congratulation, pluming themselves on innovations that others suspect are merely willful or modish. An avant-garde likes to present itself as insurgent and radical, yet the logic of the metaphor suggests that a new group will soon be coming along to replace it. Today’s avant-garde is always liable to congeal into tomorrow’s orthodoxy.

The idea of an “avant-garde” tends to inspire complex emotions, oscillating between excitement at its glamour and scorn at its pretensions. The term carries an association of being daring, experimental, unconventional; the main body of practice or opinion that it is in “advance” of is usually figured as a monolith of dull orthodoxy. But the label also easily attracts a lightly ironical coating, in which those so designated are held to be exhibiting an excess of self-consciousness or even self-congratulation, pluming themselves on innovations that others suspect are merely willful or modish. An avant-garde likes to present itself as insurgent and radical, yet the logic of the metaphor suggests that a new group will soon be coming along to replace it. Today’s avant-garde is always liable to congeal into tomorrow’s orthodoxy.

More here.

Why are some people mosquito magnets and others unbothered?

Jonathan Day in The Conversation:

As a medical entomologist who’s worked with mosquitoes for more than 40 years, I’m often asked why some people seem to be mosquito magnets while others are oblivious to these blood-feeding pests buzzing all around them.

As a medical entomologist who’s worked with mosquitoes for more than 40 years, I’m often asked why some people seem to be mosquito magnets while others are oblivious to these blood-feeding pests buzzing all around them.

Most mosquito species, along with a host of other arthropods – including ticks, fleas, bedbugs, blackflies, horseflies and biting midges – require the protein in blood to develop a batch of eggs. Only the female mosquito feeds on blood. Males feed on plant nectar, which they convert to energy for flight.

Blood-feeding is an incredibly important part of the mosquito’s reproductive cycle. Because of this, a tremendous amount of evolutionary pressure has been placed on female mosquitoes to identify potential sources of blood, quickly and efficiently get a full blood meal, and then stealthily depart the unlucky victim.

More here.

How Modernity Swallowed Islamism

Shadi Hamid in First Things:

The Middle East was ahead of its time—and certainly ahead of the West—on at least one thing: existential debates over culture, identity, and religion. During the heady, sometimes frightening days of the Arab Spring, the region was struggling over some of the same questions Americans are contending with today. What does it mean to be a nation? What do citizens need to agree on in order to be or become a people? Must the “people” be united, or can they be divided?

The Middle East was ahead of its time—and certainly ahead of the West—on at least one thing: existential debates over culture, identity, and religion. During the heady, sometimes frightening days of the Arab Spring, the region was struggling over some of the same questions Americans are contending with today. What does it mean to be a nation? What do citizens need to agree on in order to be or become a people? Must the “people” be united, or can they be divided?

The fall of stagnant Arab autocracies opened up a divide over religion, illiberalism, and the relationship between Islam and the state. Liberalism—with its emphasis on nonnegotiable freedoms, individual autonomy, and minority rights—faced an uphill battle. Liberalism requires liberals, and there simply weren’t enough of them.

In the Middle East, Muslims went further, because they could. In the absence of a preexisting liberal consensus, alternatives to liberalism—in the form of Islamism—weren’t merely considered; they were voted into power.

More here.

Your Mass is NOT From the Higgs Boson

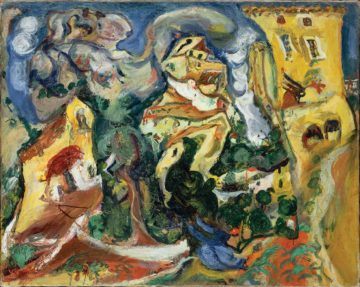

History’s Painter: Benjamin H.D. Buchloh’s “Gerhard Richter”

Daniel Spaulding at Art In America:

In criticism as in war, the law of proportionate response enjoys only occasional observance. Gerhard Richter: Painting after the Subject of History is the fruit of what its author, art historian Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, calls the “nearly unfathomable duration” of his engagement with the most influential German painter since World War II. “Unfathomable” is an overstatement, but only just. Buchloh has been thinking about Richter for half a century. The result is a book that comes in at just over 650 pages divvied up between no fewer than 20 chapters, most of which began as independent essays published between the 1980s and the present.

In criticism as in war, the law of proportionate response enjoys only occasional observance. Gerhard Richter: Painting after the Subject of History is the fruit of what its author, art historian Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, calls the “nearly unfathomable duration” of his engagement with the most influential German painter since World War II. “Unfathomable” is an overstatement, but only just. Buchloh has been thinking about Richter for half a century. The result is a book that comes in at just over 650 pages divvied up between no fewer than 20 chapters, most of which began as independent essays published between the 1980s and the present.

Curiously, given that Richter is by all evidence Buchloh’s favorite artist (or at any rate, the one who sustains the biggest share of his attention), their relationship has been marked from the beginning by profound differences of approach.

more here.

For humans, biologically speaking, soul mates are entirely real. But just like all relationships, soul mates can be complicated. Of course, there isn’t a scientifically agreed-upon definition for “soul mate.” But humans are in a small club in the animal kingdom that can form long-term relationships. I’m not talking about sexual monogamy. Humans evolved with the neurocircuitry to see another person as special. We have the capacity to single someone out from the crowd, elevate them above all others and then spend decades with them.

For humans, biologically speaking, soul mates are entirely real. But just like all relationships, soul mates can be complicated. Of course, there isn’t a scientifically agreed-upon definition for “soul mate.” But humans are in a small club in the animal kingdom that can form long-term relationships. I’m not talking about sexual monogamy. Humans evolved with the neurocircuitry to see another person as special. We have the capacity to single someone out from the crowd, elevate them above all others and then spend decades with them.

Several decades ago, it took a stand-up comedian like Steven Wright to work in shades of the brilliantly surreal when

Several decades ago, it took a stand-up comedian like Steven Wright to work in shades of the brilliantly surreal when