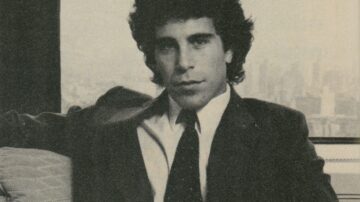

Brock Eldon at Salmagundi:

At dawn Hanoi is already awake. Motorbikes swarm beneath balconies before the light has quite broken, a mechanical chorus that carries the city into motion. From the window of my apartment overlooking Tây Hồ, the lake lies bruised with mist until the first glare of sun turns it to metal. On the street below, vendors set down baskets of fruit, incense burns outside a pagoda, and the smell of French bread mingles with diesel.

At dawn Hanoi is already awake. Motorbikes swarm beneath balconies before the light has quite broken, a mechanical chorus that carries the city into motion. From the window of my apartment overlooking Tây Hồ, the lake lies bruised with mist until the first glare of sun turns it to metal. On the street below, vendors set down baskets of fruit, incense burns outside a pagoda, and the smell of French bread mingles with diesel.

In the Vietnamese capital, even silence is crowded. Horns blare and drills hammer, and as, within the old, French-colonial styled cafés, students bend over notebooks, a young couple exchanges muted laughter, and one senses here a discipline of attention beneath the noise. Hanoi thrives on density, on each body finding rhythm within the mass of the whole.

This is not Ontario—not the Canada I was born into, where winter silences mean absence, where a child can walk for hours without encountering another soul, where a man can freeze to death just for being outside too long. Silence, in Hanoi, is suspension rather than vacancy: a pause inside intensity. To write and teach here is to live against a double register—abundance and estrangement, presence and dislocation.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

With the arrival of

With the arrival of  In Mexico City on 27 September 1842, a man was delivering an unusual eulogy. Fixing his eyes on what he called ‘the mutilated remains of an illustrious leader of independence’, the speaker was so moved that he felt he must ‘shed ardent tears over the remains of the hero’ before him. The occasion, however, was not quite as sad as he made out. For the hero, Antonio López de Santa Anna, a general and many times president of Mexico, was listening to the speech. What was being buried, for the second time, was a leg the general had lost in battle years earlier. Santa Anna was attached to his leg, even if it was no longer attached to him. Now president, he had organised for it to be disinterred, brought to Mexico City in a glass case like a holy relic and then reburied with pomp and ceremony beneath a lavish monument. Two years later, after a revolt toppled Santa Anna from power, the leg was exhumed again and dragged through the streets while people shouted, ‘Kill the lame bastard!’ and ‘Death to the cripple!’ Less than two years after that, in 1846, Santa Anna was president once more, charged with defending Mexico against US invasion. He was not up to the task, and soon the Stars and Stripes was unfurled over the magnificent central square in the capital city. The occupying US troops left only after Mexico was forced to sign away half its national territory, including present-day California.

In Mexico City on 27 September 1842, a man was delivering an unusual eulogy. Fixing his eyes on what he called ‘the mutilated remains of an illustrious leader of independence’, the speaker was so moved that he felt he must ‘shed ardent tears over the remains of the hero’ before him. The occasion, however, was not quite as sad as he made out. For the hero, Antonio López de Santa Anna, a general and many times president of Mexico, was listening to the speech. What was being buried, for the second time, was a leg the general had lost in battle years earlier. Santa Anna was attached to his leg, even if it was no longer attached to him. Now president, he had organised for it to be disinterred, brought to Mexico City in a glass case like a holy relic and then reburied with pomp and ceremony beneath a lavish monument. Two years later, after a revolt toppled Santa Anna from power, the leg was exhumed again and dragged through the streets while people shouted, ‘Kill the lame bastard!’ and ‘Death to the cripple!’ Less than two years after that, in 1846, Santa Anna was president once more, charged with defending Mexico against US invasion. He was not up to the task, and soon the Stars and Stripes was unfurled over the magnificent central square in the capital city. The occupying US troops left only after Mexico was forced to sign away half its national territory, including present-day California. Weeks ago, the sweet family across the street put up their festive holiday lights. The house on the corner followed, then three more houses, all before I had even managed to order a Thanksgiving turkey.

Weeks ago, the sweet family across the street put up their festive holiday lights. The house on the corner followed, then three more houses, all before I had even managed to order a Thanksgiving turkey. M

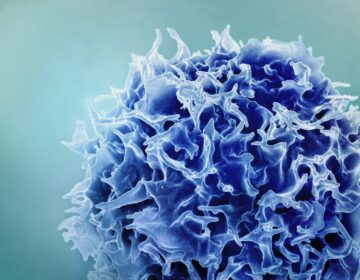

M With just a single injection, a new treatment transforms immune cells in cancer patients into efficient tumor-killing machines. Now equipped with homing beacons, the cells rapidly track down and destroy their cancerous foes.

With just a single injection, a new treatment transforms immune cells in cancer patients into efficient tumor-killing machines. Now equipped with homing beacons, the cells rapidly track down and destroy their cancerous foes. When Allen Levi, a musician who had written scores of songs over his career, began writing his first novel, his plan was to finish it and stick it in a drawer. “I just wanted to see if I had the muscle to write a piece of long fiction,” he said. The resulting book, “Theo of Golden,” is about an older man who moves to a city in Georgia and begins buying 92 pencil portraits off a coffee shop wall to return them to their subjects and “rightful owners.” After a group of Levi’s friends read the novel and encouraged him not to let the manuscript molder, he self-published it through Amazon in the fall of 2023.

When Allen Levi, a musician who had written scores of songs over his career, began writing his first novel, his plan was to finish it and stick it in a drawer. “I just wanted to see if I had the muscle to write a piece of long fiction,” he said. The resulting book, “Theo of Golden,” is about an older man who moves to a city in Georgia and begins buying 92 pencil portraits off a coffee shop wall to return them to their subjects and “rightful owners.” After a group of Levi’s friends read the novel and encouraged him not to let the manuscript molder, he self-published it through Amazon in the fall of 2023. O

O

Waymo’s co-CEO Tekedra Mawakana made a striking prediction this week:

Waymo’s co-CEO Tekedra Mawakana made a striking prediction this week: This has been a year in which terrible ideas buried and forgotten rose from the dead and ate many brains.

This has been a year in which terrible ideas buried and forgotten rose from the dead and ate many brains. John J. Lennon is, at the moment, probably this country’s foremost imprisoned journalist. This title won’t be taken from him any time soon, not because there aren’t many talented and inquisitive people in prison but because the barriers to entry are so nearly impassible. A journalist’s life is a daunting prospect these days even to a person with freedom of movement, a real computer, the ability to make phone calls in private. Lennon’s new book, The Tragedy of True Crime, concludes with an author’s note that describes the makeshifts that he and his supporters have had to adopt so he can fulfill the most basic parts of an author’s job:

John J. Lennon is, at the moment, probably this country’s foremost imprisoned journalist. This title won’t be taken from him any time soon, not because there aren’t many talented and inquisitive people in prison but because the barriers to entry are so nearly impassible. A journalist’s life is a daunting prospect these days even to a person with freedom of movement, a real computer, the ability to make phone calls in private. Lennon’s new book, The Tragedy of True Crime, concludes with an author’s note that describes the makeshifts that he and his supporters have had to adopt so he can fulfill the most basic parts of an author’s job: In January this year, an announcement from China rocked the world of artificial intelligence. The firm DeepSeek released its

In January this year, an announcement from China rocked the world of artificial intelligence. The firm DeepSeek released its  One evening in early 1976, a bushy-haired Jeffrey Epstein showed up for an event at an art gallery in Midtown Manhattan. Epstein was a math and physics teacher at the city’s prestigious Dalton School, and the father of one of his students had invited him. Epstein initially demurred, saying he didn’t go out much, but eventually relented. It would turn out to be one of the best decisions he ever made.

One evening in early 1976, a bushy-haired Jeffrey Epstein showed up for an event at an art gallery in Midtown Manhattan. Epstein was a math and physics teacher at the city’s prestigious Dalton School, and the father of one of his students had invited him. Epstein initially demurred, saying he didn’t go out much, but eventually relented. It would turn out to be one of the best decisions he ever made. In the winter

In the winter