Amir Arian in The Baffler:

“THIS TIME THERE IS NO WAY BACK,” Hamid said. “People have imagined life without them.”

“THIS TIME THERE IS NO WAY BACK,” Hamid said. “People have imagined life without them.”

He had to yell these words into his phone to record the WhatsApp voice message he sent me, or else the background din would have drowned him out. He was standing on a street in Tehran, in the thick of a protest on an early autumn afternoon. Around him, people were chanting in one moment and stampeding the next while cars roared and honked, paintballs hissed, and police sirens shrieked. He was forced to run for safety before he could finish speaking, so his last words were interrupted by panting. Despite the danger, his voice was loaded with excitement.

Hamid and I have been friends for nearly twenty years. We regularly met to talk politics while I was in Iran and stayed in touch after I left. The last time I heard him speak so excitedly was in June 2009, during the early days of the Green Movement, which rose in protest of the result of the presidential elections.

I listened to his message in my home in a small town in upstate New York.

More here.

Friday’s

Friday’s  Liza Batkin in the New York Review of Books:

Liza Batkin in the New York Review of Books: Alberto Toscano in Sidecar:

Alberto Toscano in Sidecar: Nubar Hovsepian and

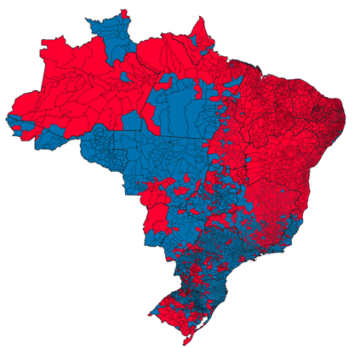

Nubar Hovsepian and  Pedro Mendes Loureiro in Phenomenal World:

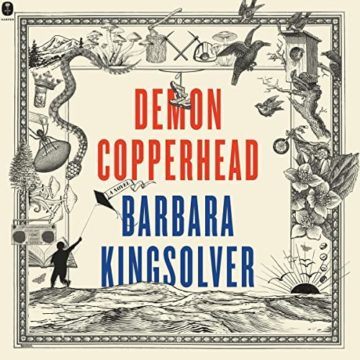

Pedro Mendes Loureiro in Phenomenal World: It’s barely Halloween. The ball won’t drop in Times Square for another two full months, and more good books will surely appear before the year ends. But I already know: My favorite novel of 2022 is Barbara Kingsolver’s “

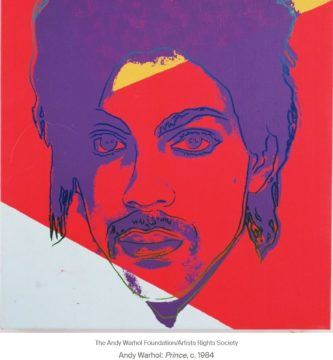

It’s barely Halloween. The ball won’t drop in Times Square for another two full months, and more good books will surely appear before the year ends. But I already know: My favorite novel of 2022 is Barbara Kingsolver’s “ The K stands for “Kindred.” It was a family name, but if there’s anyone who can forgive a fanciful imputation of significance, it is Philip K. Dick. How lovely that a poet of alienation would come into existence bearing that word.

The K stands for “Kindred.” It was a family name, but if there’s anyone who can forgive a fanciful imputation of significance, it is Philip K. Dick. How lovely that a poet of alienation would come into existence bearing that word. In his new book, “The Song of the Cell,” Siddhartha Mukherjee has taken on a subject that is enormous and minuscule at once. Even though cells are typically so tiny that you need a microscope to see them, they also happen to be implicated in almost anything to do with medicine — and therefore almost anything to do with life. Guided by Mukherjee’s granular narration (“As you keep swimming through the cell’s protoplasm …”), I was repeatedly dazzled by his pointillist scenes, the enthusiasm of his explanations, the immediacy of his metaphors. But I also found myself wondering where we were going. What kind of organism might these smaller units add up to? What was the shape of the story he set out to tell?

In his new book, “The Song of the Cell,” Siddhartha Mukherjee has taken on a subject that is enormous and minuscule at once. Even though cells are typically so tiny that you need a microscope to see them, they also happen to be implicated in almost anything to do with medicine — and therefore almost anything to do with life. Guided by Mukherjee’s granular narration (“As you keep swimming through the cell’s protoplasm …”), I was repeatedly dazzled by his pointillist scenes, the enthusiasm of his explanations, the immediacy of his metaphors. But I also found myself wondering where we were going. What kind of organism might these smaller units add up to? What was the shape of the story he set out to tell? Now comes news of a maniac breaking into a house in the middle of the night, bludgeoning an 82-year-old man in the head with a hammer while demanding to know where his famous wife was. Perfect Halloween movie fare. Except it actually happened. One of the most macabre stories to come out of the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol and democracy, ginned up by Donald Trump, was when the mob roamed the halls, pounding the speaker’s door with bloodcurdling taunts of “Where’s Nancy?” Speaker Pelosi was not there, thank God. She was huddling with other top officials in a secure bunker, placing call after call for help that was slow to arrive.

Now comes news of a maniac breaking into a house in the middle of the night, bludgeoning an 82-year-old man in the head with a hammer while demanding to know where his famous wife was. Perfect Halloween movie fare. Except it actually happened. One of the most macabre stories to come out of the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol and democracy, ginned up by Donald Trump, was when the mob roamed the halls, pounding the speaker’s door with bloodcurdling taunts of “Where’s Nancy?” Speaker Pelosi was not there, thank God. She was huddling with other top officials in a secure bunker, placing call after call for help that was slow to arrive. Imagine taking in an orphaned baby bird, giving it food and shelter so that it could grow, and then one day it swoops down and attacks the family hamster.

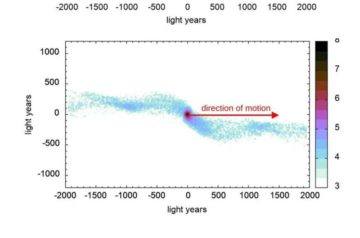

Imagine taking in an orphaned baby bird, giving it food and shelter so that it could grow, and then one day it swoops down and attacks the family hamster. An international team of astrophysicists has made a puzzling discovery while analyzing certain star clusters. The finding challenges Newton’s laws of gravity, the researchers write in their publication. Instead, the observations are consistent with the predictions of an alternative theory of gravity. However, this is controversial among experts. The results have now been published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

An international team of astrophysicists has made a puzzling discovery while analyzing certain star clusters. The finding challenges Newton’s laws of gravity, the researchers write in their publication. Instead, the observations are consistent with the predictions of an alternative theory of gravity. However, this is controversial among experts. The results have now been published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. Homo sapiens have existed on the planet for

Homo sapiens have existed on the planet for  The astounding influence that Chinese poetry in translation has had on the English language throughout the 20th century—from the Modernist, Imagist revolution of

The astounding influence that Chinese poetry in translation has had on the English language throughout the 20th century—from the Modernist, Imagist revolution of  What counts as resurrection? A general rising of the dead, a return from the afterworld at the end of time in some physical embodiment, is specific to a small group of monotheistic religions: Zoroastrianism, Islam, Judaism, Christianity. Irksome sympathizers say that the dead person will “live” in memory. Reincarnation, especially prevalent in the belief systems collected under Hinduism, is an expansive view of resurrection. The “undead”—whether zombies or ghosts—cluster at the threshold of living again. Science fiction and the superrich try to upload the self to a mechanical container. Some physicists propose the eventuality of a quantum resurrection out there in this universe or another. The corpse fertilizes the cemetery grass. What I began seeking, though, was a straight-up rewinding, my own Lazarus, selfsame.

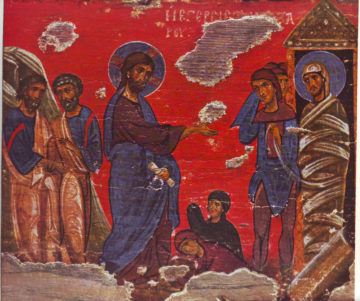

What counts as resurrection? A general rising of the dead, a return from the afterworld at the end of time in some physical embodiment, is specific to a small group of monotheistic religions: Zoroastrianism, Islam, Judaism, Christianity. Irksome sympathizers say that the dead person will “live” in memory. Reincarnation, especially prevalent in the belief systems collected under Hinduism, is an expansive view of resurrection. The “undead”—whether zombies or ghosts—cluster at the threshold of living again. Science fiction and the superrich try to upload the self to a mechanical container. Some physicists propose the eventuality of a quantum resurrection out there in this universe or another. The corpse fertilizes the cemetery grass. What I began seeking, though, was a straight-up rewinding, my own Lazarus, selfsame.