John-Baptiste Oduor in The Nation:

The philosopher Stanley Cavell, who was the author of some 19 books, passed away in 2018. Fifteen years earlier, he had turned his attention to his death in Little Did I Know, a memoir occasioned by the discovery of his own declining health. There, as in much of his work, he was comfortable writing in the retrospective mode, reflecting again and again on his most famous collection of essays, Must We Mean What We Say? (1969), and the arguments, ideas, and distinctive style he developed there. The latter would be described by his critics as self-indulgent and by his defenders as profound. The reality was somewhere between these judgments, although often closer to the former than the latter.

The philosopher Stanley Cavell, who was the author of some 19 books, passed away in 2018. Fifteen years earlier, he had turned his attention to his death in Little Did I Know, a memoir occasioned by the discovery of his own declining health. There, as in much of his work, he was comfortable writing in the retrospective mode, reflecting again and again on his most famous collection of essays, Must We Mean What We Say? (1969), and the arguments, ideas, and distinctive style he developed there. The latter would be described by his critics as self-indulgent and by his defenders as profound. The reality was somewhere between these judgments, although often closer to the former than the latter.

Like his mother, Fannie Goldstein, Cavell began and then abandoned a career in music. Although she gave up music to work occasionally in her husband Irving’s pawnshop in Atlanta, Cavell would leave the arts for philosophy and at 16 would change his name to an anglicized version of Kavelieruskii, the name his father had exchanged for Goldstein on arriving in America from Poland.

More here.

As an evolutionary biologist, I am quite used to attempts to censor research and suppress knowledge. But for most of my career, that kind of behavior came from the right. In the old days, most students and administrators were actually on our side; we were aligned against creationists. Now, the threat comes mainly from the left.

As an evolutionary biologist, I am quite used to attempts to censor research and suppress knowledge. But for most of my career, that kind of behavior came from the right. In the old days, most students and administrators were actually on our side; we were aligned against creationists. Now, the threat comes mainly from the left. It isn’t just pundits and commentators who are annoyed with the state of macro; economists in other fields often join in the criticism. For example, here’s

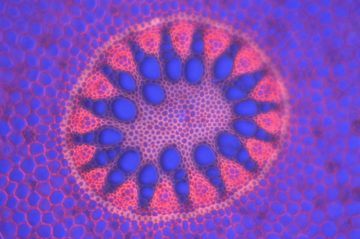

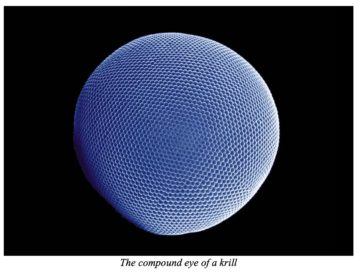

It isn’t just pundits and commentators who are annoyed with the state of macro; economists in other fields often join in the criticism. For example, here’s  One of the last flashes of creativity I saw before I deactivated my Twitter account (more on that below, and on its significance for this Substack project), was a question launched by another user (whom I can’t locate now, without Twitter, but to whom I say “thanks”). “Are there,” this user asked, “more eyes or legs in the world?”

One of the last flashes of creativity I saw before I deactivated my Twitter account (more on that below, and on its significance for this Substack project), was a question launched by another user (whom I can’t locate now, without Twitter, but to whom I say “thanks”). “Are there,” this user asked, “more eyes or legs in the world?” Moving to daylight saving time permanently could prevent 36,550 deer deaths, 33 human deaths and $1.19 billion in costs annually in the US.

Moving to daylight saving time permanently could prevent 36,550 deer deaths, 33 human deaths and $1.19 billion in costs annually in the US. People have a complicated relationship to mathematics. We all use it in our everyday lives, from calculating a tip at a restaurant to estimating the probability of some future event. But many people find the subject intimidating, if not off-putting. John Allen Paulos has long been working to make mathematics more approachable and encourage people to become more numerate. We talk about how people think about math, what kinds of math they should know, and the role of stories and narrative to make math come alive.

People have a complicated relationship to mathematics. We all use it in our everyday lives, from calculating a tip at a restaurant to estimating the probability of some future event. But many people find the subject intimidating, if not off-putting. John Allen Paulos has long been working to make mathematics more approachable and encourage people to become more numerate. We talk about how people think about math, what kinds of math they should know, and the role of stories and narrative to make math come alive. So can we find final value in the world? I believe that we can, so long as we are attuned to aesthetic value. Aesthetic value is a catch-all term that encompasses the beautiful, the ugly, the sublime, the dramatic, the comic, the cute, the kitsch, the uncanny, and many other related concepts. It is a well-worn cliché that the practical person scorns aesthetic value. But there’s reason to think that it is the only way in which we can draw final positive value from the entire world. Thus, to the extent that we care whether or not we live in a good world, we must be aesthetically sensitive.

So can we find final value in the world? I believe that we can, so long as we are attuned to aesthetic value. Aesthetic value is a catch-all term that encompasses the beautiful, the ugly, the sublime, the dramatic, the comic, the cute, the kitsch, the uncanny, and many other related concepts. It is a well-worn cliché that the practical person scorns aesthetic value. But there’s reason to think that it is the only way in which we can draw final positive value from the entire world. Thus, to the extent that we care whether or not we live in a good world, we must be aesthetically sensitive. BEING A TRUTH-TELLING

BEING A TRUTH-TELLING “Undine Spragg—how can you?” her mother wailed, raising a prematurely-wrinkled hand heavy with rings to defend the note which a languid “bell-boy” had just brought in.

“Undine Spragg—how can you?” her mother wailed, raising a prematurely-wrinkled hand heavy with rings to defend the note which a languid “bell-boy” had just brought in. T

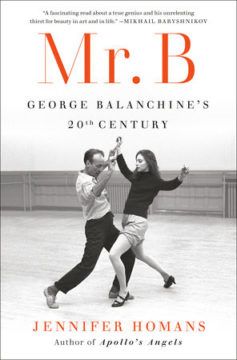

T Opera is all about saying goodbye, Virgil Thomson is reputed to have said, and ballet is all about saying hello.

Opera is all about saying goodbye, Virgil Thomson is reputed to have said, and ballet is all about saying hello. F

F