Heidi Ledford in Nature:

On 12 September, Amgen announced that the latest trial of sotorasib found that it extended progression-free survival — a measure of the time elapsed without the cancer worsening — only by about one month longer than standard chemotherapy. Only 28% of the participants treated with sotorasib responded to it. That’s roughly twice the number who responded to the standard chemotherapy, but a sign nonetheless that most people who have KRAS-positive lung cancers will not be helped by the new drug.

On 12 September, Amgen announced that the latest trial of sotorasib found that it extended progression-free survival — a measure of the time elapsed without the cancer worsening — only by about one month longer than standard chemotherapy. Only 28% of the participants treated with sotorasib responded to it. That’s roughly twice the number who responded to the standard chemotherapy, but a sign nonetheless that most people who have KRAS-positive lung cancers will not be helped by the new drug.

Even so, the pace of KRAS research and the pursuit of KRAS-targeting drugs has never been so energized, says cancer biologist Channing Der at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. The first glimpse of success has shown that it is possible to drug the ‘undruggable’ KRAS, and now researchers in academia and industry are developing ways to improve their approach. “I have never seen this level of excitement and buzz in the entire history of the field,” he says. “The level now is insane.”

More here.

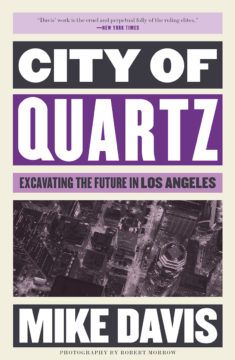

Mike Davis, author and activist, radical hero and family man, died October 25 after a long struggle with esophageal cancer; he was 76. He’s best known for his 1990 book about Los Angeles, City of Quartz. Marshall Berman, reviewing it for The Nation,

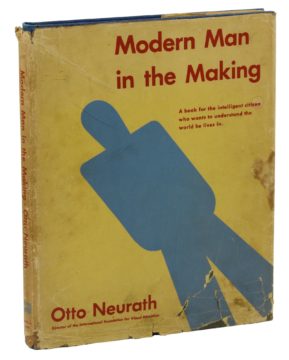

Mike Davis, author and activist, radical hero and family man, died October 25 after a long struggle with esophageal cancer; he was 76. He’s best known for his 1990 book about Los Angeles, City of Quartz. Marshall Berman, reviewing it for The Nation,  In 1939, the Viennese economist and sociologist Otto Neurath (1882–1945) released Modern Man in the Making to an American public. Published by Alfred A. Knopf, Neurath’s pictorial statistical history of human technological adaptation and social cooperation addressed a modern audience searching for optimistic narratives amid an economically, politically, and socially volatile era. If not actual members of the managerial class, readers of Neurath’s book were immersed in a “culture of management” that permeated many aspects of modern life. The concerns of the broader public were addressed by managerial commitments to profitable business and social betterment through the promotion of efficiency during the interwar years. Between 1917 and 1939 Neurath frequently referenced Scientific Management and its program for promoting cooperation through efficiency. Abandoning theology and enlightenment liberalism, he even went so far as to propose an ethics modeled on an extrapolation of Scientific Management which would take the form of the extension of convention and habit into new forms of life.

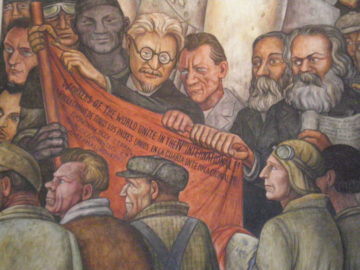

In 1939, the Viennese economist and sociologist Otto Neurath (1882–1945) released Modern Man in the Making to an American public. Published by Alfred A. Knopf, Neurath’s pictorial statistical history of human technological adaptation and social cooperation addressed a modern audience searching for optimistic narratives amid an economically, politically, and socially volatile era. If not actual members of the managerial class, readers of Neurath’s book were immersed in a “culture of management” that permeated many aspects of modern life. The concerns of the broader public were addressed by managerial commitments to profitable business and social betterment through the promotion of efficiency during the interwar years. Between 1917 and 1939 Neurath frequently referenced Scientific Management and its program for promoting cooperation through efficiency. Abandoning theology and enlightenment liberalism, he even went so far as to propose an ethics modeled on an extrapolation of Scientific Management which would take the form of the extension of convention and habit into new forms of life. Diego Rivera painted

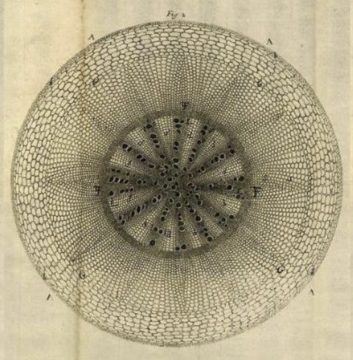

Diego Rivera painted  Modern genetics was launched by the practice of agriculture: the Moravian monk Gregor Mendel discovered genes by cross-pollinating peas with a paintbrush in his monastery garden in Brno. The Russian geneticist Nikolai Vavilov was inspired by crop selection. Even the English naturalist Charles Darwin had noted the extreme changes in animal forms created by selective breeding. Cell biology, too, was instigated by an unassuming, practical technology. Highbrow science was born from lowbrow tinkering.

Modern genetics was launched by the practice of agriculture: the Moravian monk Gregor Mendel discovered genes by cross-pollinating peas with a paintbrush in his monastery garden in Brno. The Russian geneticist Nikolai Vavilov was inspired by crop selection. Even the English naturalist Charles Darwin had noted the extreme changes in animal forms created by selective breeding. Cell biology, too, was instigated by an unassuming, practical technology. Highbrow science was born from lowbrow tinkering. In his classic book from 1990, Three Rival Versions of Moral Inquiry, the Marxist-turned-Catholic-Thomist philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre discusses three basic modern and postmodern approaches to philosophical inquiry: encyclopedia, genealogy, and tradition. The genealogical method, pioneered by Friedrich Nietzsche and elaborated by Michel Foucault, presents a historical narrative in which ideas develop and grow over time. According to this thinking, being and truth are conditioned by history (historicized) and thus develop in tandem with the twists and turns of science, technology, economics, language, and culture.

In his classic book from 1990, Three Rival Versions of Moral Inquiry, the Marxist-turned-Catholic-Thomist philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre discusses three basic modern and postmodern approaches to philosophical inquiry: encyclopedia, genealogy, and tradition. The genealogical method, pioneered by Friedrich Nietzsche and elaborated by Michel Foucault, presents a historical narrative in which ideas develop and grow over time. According to this thinking, being and truth are conditioned by history (historicized) and thus develop in tandem with the twists and turns of science, technology, economics, language, and culture. At the end of my sophomore year of college, I found myself at a career crossroads. The pandemic hit a few months earlier and like most students across the country, I was kicked off campus and sent back home. As I spent the remainder of the school year sitting idly in my childhood bedroom, I had no choice but to wrestle with the ever-looming question: What do I really want to do with my life?

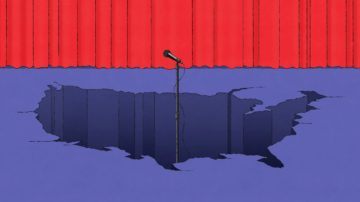

At the end of my sophomore year of college, I found myself at a career crossroads. The pandemic hit a few months earlier and like most students across the country, I was kicked off campus and sent back home. As I spent the remainder of the school year sitting idly in my childhood bedroom, I had no choice but to wrestle with the ever-looming question: What do I really want to do with my life? Tours have always been good for getting me out of my bubble, this one even more so. Driving across the Midwest, I saw one Trump 2024 sign after another—this while the election was an entire three years away. “You know you’re in a place that’s inhospitable to liberals when you see fireworks stores,” Adam said in rural Indiana as we passed one powder keg after another.

Tours have always been good for getting me out of my bubble, this one even more so. Driving across the Midwest, I saw one Trump 2024 sign after another—this while the election was an entire three years away. “You know you’re in a place that’s inhospitable to liberals when you see fireworks stores,” Adam said in rural Indiana as we passed one powder keg after another. W

W According to poetry scholar John Timberman Newcomb, Millay is “

According to poetry scholar John Timberman Newcomb, Millay is “ The founders of statistical mechanics in the 19th century faced an uphill battle to convince their fellow physicists that the laws of thermodynamics could be derived from the random motions of microscopic atoms. This insight turns out to be even more important than they realized: the emergence of patterns characterizing our macroscopic world relies crucially on the increase of entropy over time. Barry Loewer has (in collaboration with David Albert) been developing a theory of the

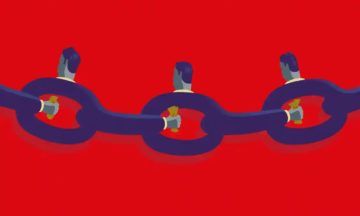

The founders of statistical mechanics in the 19th century faced an uphill battle to convince their fellow physicists that the laws of thermodynamics could be derived from the random motions of microscopic atoms. This insight turns out to be even more important than they realized: the emergence of patterns characterizing our macroscopic world relies crucially on the increase of entropy over time. Barry Loewer has (in collaboration with David Albert) been developing a theory of the  Nothing destroys progress like conflict. Fighting massacres soldiers, ravages civilians, starves cities, plunders stores, disrupts trade, demolishes industry, and bankrupts governments. It undermines economic growth in indirect ways too. Most people and business won’t do the basic activities that lead to development when they expect bombings, ethnic cleansing, or arbitrary justice; they won’t specialize in tasks, trade, invest their wealth, or develop new ideas. These costs of war incentivize rivals to steer clear from prolonged and intense violence.

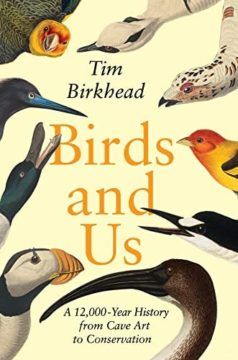

Nothing destroys progress like conflict. Fighting massacres soldiers, ravages civilians, starves cities, plunders stores, disrupts trade, demolishes industry, and bankrupts governments. It undermines economic growth in indirect ways too. Most people and business won’t do the basic activities that lead to development when they expect bombings, ethnic cleansing, or arbitrary justice; they won’t specialize in tasks, trade, invest their wealth, or develop new ideas. These costs of war incentivize rivals to steer clear from prolonged and intense violence. Relationships between ancient humans and birds had a deeply religious element. Birkhead locates the “ground zero” of an early human civilization built around animal worship in ancient Egypt. Within the catacombs at Tuna el-Gebel in Egypt, there are four million mummified birds contained in jars and coffins. In addition to mummifying ibises, ancient Egyptians preserved a variety of creatures in cemeteries throughout the Nile Valley. Birds, however, are among the most prominent animals. Clearly, the lovingly embalmed birds were considered sacred; and ancient Egypt was a civilization in which humans and birds lived in harmony.

Relationships between ancient humans and birds had a deeply religious element. Birkhead locates the “ground zero” of an early human civilization built around animal worship in ancient Egypt. Within the catacombs at Tuna el-Gebel in Egypt, there are four million mummified birds contained in jars and coffins. In addition to mummifying ibises, ancient Egyptians preserved a variety of creatures in cemeteries throughout the Nile Valley. Birds, however, are among the most prominent animals. Clearly, the lovingly embalmed birds were considered sacred; and ancient Egypt was a civilization in which humans and birds lived in harmony. Protests enter their second week. I’m waiting on the street for the taxi to arrive when I see an old religious man coming towards me. At first, I’m afraid he wants to mention I’m not wearing a hijab. All of a sudden, he brings his phone in front of me and shows me Mahsa Amini’s photo, saying, “Can you believe it, ma’am? They killed someone’s daughter. I myself have a daughter. I swear to God, I haven’t slept for a week.”

Protests enter their second week. I’m waiting on the street for the taxi to arrive when I see an old religious man coming towards me. At first, I’m afraid he wants to mention I’m not wearing a hijab. All of a sudden, he brings his phone in front of me and shows me Mahsa Amini’s photo, saying, “Can you believe it, ma’am? They killed someone’s daughter. I myself have a daughter. I swear to God, I haven’t slept for a week.”