Hannah Thomasy in The New York Times:

Ned and Sunny stretch out together on the warm sand. He rests his head on her back, and every so often he might give her an affectionate nudge with his nose. The pair is quiet and, like many long-term couples, they seem perfectly content just to be in each other’s presence.

Ned and Sunny stretch out together on the warm sand. He rests his head on her back, and every so often he might give her an affectionate nudge with his nose. The pair is quiet and, like many long-term couples, they seem perfectly content just to be in each other’s presence.

The couple are monogamous, which is quite rare in the animal kingdom. But Sunny and Ned are a bit scalier that your typical lifelong mates — they are shingleback lizards that live at Melbourne Museum in Australia. In the wild, shinglebacks regularly form long-term bonds, returning to the same partner during mating season year after year. One lizard couple in a long-term study had been pairing up for 27 years and were still going strong when the study ended. In this way, the reptiles are more like some of the animal kingdom’s most famous long-term couplers, such as albatrosses, prairie voles and owl monkeys, and they confound expectations many people have about the personalities of lizards. “There’s more socially going on with reptiles than we give them credit for,” said Sean Doody, a conservation biologist at the University of South Florida.

More here.

Annie Ernaux, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature last Thursday, was not on the other end of the telephone when the committee rang to deliver the news. Last year, she received a prank text telling her she had won the illustrious award, which might be one reason why her first response when the committee did get through to her was incredulous: “Are you sure?”

Annie Ernaux, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature last Thursday, was not on the other end of the telephone when the committee rang to deliver the news. Last year, she received a prank text telling her she had won the illustrious award, which might be one reason why her first response when the committee did get through to her was incredulous: “Are you sure?” Matrix multiplication, which

Matrix multiplication, which

Last year, according to data from the BP Statistical Review of World Energy, in both the US, and the world as a whole, the growth in hydrocarbons—oil, natural gas, and coal—far exceeded the growth of wind and solar by huge margins.

Last year, according to data from the BP Statistical Review of World Energy, in both the US, and the world as a whole, the growth in hydrocarbons—oil, natural gas, and coal—far exceeded the growth of wind and solar by huge margins. For nearly 150 years, a cloud has hung over the reputation of Geoffrey Chaucer, the author of “The Canterbury Tales,” long seen as the founder of the English literary canon.

For nearly 150 years, a cloud has hung over the reputation of Geoffrey Chaucer, the author of “The Canterbury Tales,” long seen as the founder of the English literary canon. I

I Kate Aronoff in The New Republic (Image: Ahmed Shurau/ Getty Images):

Kate Aronoff in The New Republic (Image: Ahmed Shurau/ Getty Images):

Tobias Hübinette in Boston Review:

Tobias Hübinette in Boston Review:

F

F It’s an anti-Trumper’s nightmare, but it could happen: 47 percent of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents want Trump to be the nominee in 2024, according to a recent Washington Post-ABC News

It’s an anti-Trumper’s nightmare, but it could happen: 47 percent of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents want Trump to be the nominee in 2024, according to a recent Washington Post-ABC News  O

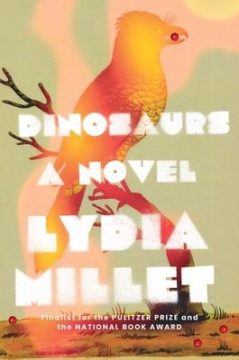

O The novelist Lydia Millet once told an interviewer that when she first moved to New York, in 1996, she was “amazed” by how people were “relentlessly interested in exclusively the human self.” This myopia—a sort of “inarticulate, ambient smugness about everything”—wasn’t her creed. Millet, who now lives near Tucson, has written more than a dozen books of fiction, one of which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, but she works at the Center for Biological Diversity and holds a master’s in environmental policy. As in life, so in art. Increasingly, fiction studies the “arc of the private individual,” Millet told another interviewer: “The personal struggles of a self and the ultimate triumph of that self over the obstacles in its path.” But Millet is energized, instead, by how feelings are “intermeshed with abstract thought,” with “our place in the wider landscape.” Why, her work demands, are we afraid to die? What are the ethics of wanting what we want?

The novelist Lydia Millet once told an interviewer that when she first moved to New York, in 1996, she was “amazed” by how people were “relentlessly interested in exclusively the human self.” This myopia—a sort of “inarticulate, ambient smugness about everything”—wasn’t her creed. Millet, who now lives near Tucson, has written more than a dozen books of fiction, one of which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, but she works at the Center for Biological Diversity and holds a master’s in environmental policy. As in life, so in art. Increasingly, fiction studies the “arc of the private individual,” Millet told another interviewer: “The personal struggles of a self and the ultimate triumph of that self over the obstacles in its path.” But Millet is energized, instead, by how feelings are “intermeshed with abstract thought,” with “our place in the wider landscape.” Why, her work demands, are we afraid to die? What are the ethics of wanting what we want?