Aatish Taseer in The New York Times:

ON A MORNING of haunting heat in Seville, I sought out the tomb of Ferdinand III. There, in the Gothic cool, older Spaniards came and went, dropping to one knee and crossing themselves before the sepulcher of the Castilian monarch. There were men in staid tucked-in shirts, gray checked with yellow, and women with short-cropped hair and knee-length dresses, slim belts around their waists. They sat in pews under a coffered ceiling, dourly communing with El Santo, the patron saint of what would come to be called La Reconquista — the man under whom five and a half centuries of Muslim rule had in 1248 come to an end in this town: Seville, or Ishbiliya, as it was known then.

ON A MORNING of haunting heat in Seville, I sought out the tomb of Ferdinand III. There, in the Gothic cool, older Spaniards came and went, dropping to one knee and crossing themselves before the sepulcher of the Castilian monarch. There were men in staid tucked-in shirts, gray checked with yellow, and women with short-cropped hair and knee-length dresses, slim belts around their waists. They sat in pews under a coffered ceiling, dourly communing with El Santo, the patron saint of what would come to be called La Reconquista — the man under whom five and a half centuries of Muslim rule had in 1248 come to an end in this town: Seville, or Ishbiliya, as it was known then.

On a banner above the altar, silver letters against a crimson ground read, “Per Me Reges Regnant” (“By Me, Kings Reign”). The Virgin of Kings, dressed in orchid pink, gazed down at this scene of historical piety. Black-haired putti, prying and vaguely deviant, swarmed around her. The organ played. Latin chants filled the ribbed recesses of the largest Gothic church in Christendom, which retained as its belfry the fabled minaret (La Giralda, or “weather vane”) of the 12th-century mosque on whose bones it had been built.

More here.

MURAKAMI: When I was writing a novel on an island in Greece, I could see a flock of sheep right outside the window and I wrote the novel every day looking at them. It’s not like the sheep helped in any special way, but they might have encouraged me. The novel I was writing then was Norwegian Wood. Not a single sheep in the story.

MURAKAMI: When I was writing a novel on an island in Greece, I could see a flock of sheep right outside the window and I wrote the novel every day looking at them. It’s not like the sheep helped in any special way, but they might have encouraged me. The novel I was writing then was Norwegian Wood. Not a single sheep in the story. In the holiday resort of Sharm El Sheikh in Egypt, the stage is being set for COP27, the next round of UN climate talks, which kicks off on 6 November.

In the holiday resort of Sharm El Sheikh in Egypt, the stage is being set for COP27, the next round of UN climate talks, which kicks off on 6 November. Severe megathreats are imperiling our future – not just our jobs, incomes, wealth, and the global economy, but also the relative peace, prosperity, and progress achieved over the past 75 years. Many of these threats were not even on our radar during the prosperous post-World War II era. I grew up in the Middle East and Europe from the late 1950s to the early 1980s, and I never worried about climate change potentially destroying the planet. Most of us had barely even heard of the problem, and greenhouse-gas emissions were still relatively low, compared to where they would soon be.

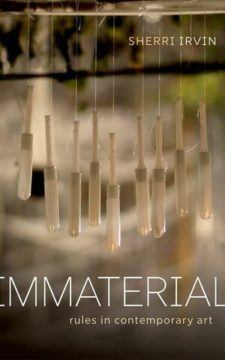

Severe megathreats are imperiling our future – not just our jobs, incomes, wealth, and the global economy, but also the relative peace, prosperity, and progress achieved over the past 75 years. Many of these threats were not even on our radar during the prosperous post-World War II era. I grew up in the Middle East and Europe from the late 1950s to the early 1980s, and I never worried about climate change potentially destroying the planet. Most of us had barely even heard of the problem, and greenhouse-gas emissions were still relatively low, compared to where they would soon be. All too often, philosophers of art (myself included) deal with art at a remove, at their desks, surrounded by books, countless tabs open in their browser windows. Reading Sherri Irvin’s book feels like you’re being led through a gallery that Irvin herself has carefully curated—indeed, led through the hidden corridors behind the gallery walls. Despite the title of this volume, Irvin makes the art she discusses feel material in a way that other philosophers just don’t—maybe can’t. Irvin makes me appreciate the art she discusses; she makes me love it.

All too often, philosophers of art (myself included) deal with art at a remove, at their desks, surrounded by books, countless tabs open in their browser windows. Reading Sherri Irvin’s book feels like you’re being led through a gallery that Irvin herself has carefully curated—indeed, led through the hidden corridors behind the gallery walls. Despite the title of this volume, Irvin makes the art she discusses feel material in a way that other philosophers just don’t—maybe can’t. Irvin makes me appreciate the art she discusses; she makes me love it. Maronite priest Antonio Fausto Naironi once claimed that the greatest of miracles happened in ninth-century Ethiopia. It was then and there, in the province of Oromia, that a young shepherd named Kaldi noticed that his goats were prone to running, leaping, and dancing after they had eaten blood-red berries from a mysterious bush. Kaldi chewed on a few beans himself, and suddenly he was awake. Gathering handfuls of them, he brought them to a local abbot. Disgusted with the very idea of such a shortcut to enlightenment, the monk threw the beans into a fire, but the other brothers smelled the delicious fragrance and gathered. Naironi is a bit scant on the details, but for some reason the grounds were filtered into water, and the first cup of coffee was brewed.

Maronite priest Antonio Fausto Naironi once claimed that the greatest of miracles happened in ninth-century Ethiopia. It was then and there, in the province of Oromia, that a young shepherd named Kaldi noticed that his goats were prone to running, leaping, and dancing after they had eaten blood-red berries from a mysterious bush. Kaldi chewed on a few beans himself, and suddenly he was awake. Gathering handfuls of them, he brought them to a local abbot. Disgusted with the very idea of such a shortcut to enlightenment, the monk threw the beans into a fire, but the other brothers smelled the delicious fragrance and gathered. Naironi is a bit scant on the details, but for some reason the grounds were filtered into water, and the first cup of coffee was brewed. “SOMETIMES I THINK

“SOMETIMES I THINK L

L The crop of Republican candidates running in the midterms has taken immorality to a whole new level. Arizona gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake has

The crop of Republican candidates running in the midterms has taken immorality to a whole new level. Arizona gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake has Newton began his quantitative derivation of Earth’s figure in 1686, after learning about work by the French physicist Jean Richer. In 1671, Richer had traveled to Cayenne, the capital of French Guiana in South America, and experimented with a pendulum clock. Richer found that the clock, calibrated to Parisian astronomical time (48°40’ latitude), lost an average of 2.5 minutes per day in Cayenne (5° latitude). This was surprising, but it could be explained by the theory of centrifugal motion, recently developed by Christian Huygens: The theory suggested that the centrifugal effect is strongest at the equator, so the net effective surface gravity would decrease as you moved from Paris to Cayenne[

Newton began his quantitative derivation of Earth’s figure in 1686, after learning about work by the French physicist Jean Richer. In 1671, Richer had traveled to Cayenne, the capital of French Guiana in South America, and experimented with a pendulum clock. Richer found that the clock, calibrated to Parisian astronomical time (48°40’ latitude), lost an average of 2.5 minutes per day in Cayenne (5° latitude). This was surprising, but it could be explained by the theory of centrifugal motion, recently developed by Christian Huygens: The theory suggested that the centrifugal effect is strongest at the equator, so the net effective surface gravity would decrease as you moved from Paris to Cayenne[ From street demonstrations to song, dance, film, and poetry, women are advancing a long legacy of struggle against authoritarianism in Iran.

From street demonstrations to song, dance, film, and poetry, women are advancing a long legacy of struggle against authoritarianism in Iran. Everyone has a type they can’t resist. For the writer Kazuo Ishiguro, it’s old men. Old men secretly worried they’ve spent entire lives on the wrong side of history. Old men born in a world of certainty, transplanted to a different, more dubious one. Old men asking themselves, as so many of us will do (if we haven’t already): ‘What was it all for?’

Everyone has a type they can’t resist. For the writer Kazuo Ishiguro, it’s old men. Old men secretly worried they’ve spent entire lives on the wrong side of history. Old men born in a world of certainty, transplanted to a different, more dubious one. Old men asking themselves, as so many of us will do (if we haven’t already): ‘What was it all for?’ I have a suggestion: Forget London. Forget, for now, the nineteenth century, forget the whole assertion that the value of the “late” or “mature,” Dickens—a construction whose first evidence is usually located by commentators here, in Dombey and Son—rests on his placement of his sentimental melodramas and grotesques in an increasingly deliberate and nuanced social portrait of his times, of his city. Forget institutions, forget reform. Please indulge me, and forget for the moment any questions of psycho-biographical excavation, of self-portraiture, despite Dombey’s being the book which preceded that great dam-bursting of the autobiographical impulse, David Copperfield (and, in fact, Dombey contains a tiny leak in that dam in the form of Mrs. Pipchin, the first character avowed by Dickens to have been drawn from a figure from his life). Forget Where’s Charles Dickens in all this fabulous contradictory stew of story and rhetoric? What does the guy want from us? What does he really think and believe? Forget it all, and then forgive what will surely seem a diminishing suggestion from me, which is that you abandon all context, ye who enter here, and read Dombey and Son as though it were a book about animals.

I have a suggestion: Forget London. Forget, for now, the nineteenth century, forget the whole assertion that the value of the “late” or “mature,” Dickens—a construction whose first evidence is usually located by commentators here, in Dombey and Son—rests on his placement of his sentimental melodramas and grotesques in an increasingly deliberate and nuanced social portrait of his times, of his city. Forget institutions, forget reform. Please indulge me, and forget for the moment any questions of psycho-biographical excavation, of self-portraiture, despite Dombey’s being the book which preceded that great dam-bursting of the autobiographical impulse, David Copperfield (and, in fact, Dombey contains a tiny leak in that dam in the form of Mrs. Pipchin, the first character avowed by Dickens to have been drawn from a figure from his life). Forget Where’s Charles Dickens in all this fabulous contradictory stew of story and rhetoric? What does the guy want from us? What does he really think and believe? Forget it all, and then forgive what will surely seem a diminishing suggestion from me, which is that you abandon all context, ye who enter here, and read Dombey and Son as though it were a book about animals. In 1665, the British polymath Robert Hooke published an unexpectedly popular picture book, “Micrographia.” It featured drawings of household objects and inhabitants that were normally barely visible—pests in particular. But they were presented at enormous magnification, having been detected by means of the cutting-edge technology of the day: a compound, two-lens microscope.

In 1665, the British polymath Robert Hooke published an unexpectedly popular picture book, “Micrographia.” It featured drawings of household objects and inhabitants that were normally barely visible—pests in particular. But they were presented at enormous magnification, having been detected by means of the cutting-edge technology of the day: a compound, two-lens microscope.