Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack Newsletter:

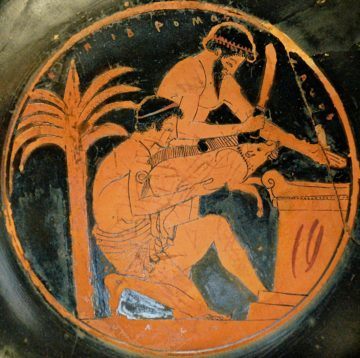

In her influential 1971 article, “A Defense of Abortion”,[1] the philosopher Judith Jarvis Thomson deploys a number of outlandish thought experiments. Among them is the story of a woman much like herself who gets kidnapped and, on awakening, finds she is attached by complicated life-support apparatuses to a great violinist. Her kidnappers explain when she awakens that she happens to be just so physiologically constituted as to be necessary for the violinist’s survival, and surely she agrees it is important to keep this rare musician alive, does she not? If she gets up and walks away, he will die; if she stays attached to him for nine months, they will both live. But, they acknowledge, she is of course free to go.

In her influential 1971 article, “A Defense of Abortion”,[1] the philosopher Judith Jarvis Thomson deploys a number of outlandish thought experiments. Among them is the story of a woman much like herself who gets kidnapped and, on awakening, finds she is attached by complicated life-support apparatuses to a great violinist. Her kidnappers explain when she awakens that she happens to be just so physiologically constituted as to be necessary for the violinist’s survival, and surely she agrees it is important to keep this rare musician alive, does she not? If she gets up and walks away, he will die; if she stays attached to him for nine months, they will both live. But, they acknowledge, she is of course free to go.

This particular scenario is one that Thomson only invokes in the course of making another point about another category of human beings than frail adult violinists, and yet it is a passing remark about his dependency on her that has preoccupied me the longest and most profoundly: we all agree, she reasons, that the person attached to the violinist is free to get up and leave, but she is not free to slit the violinist’s throat before going. Why not? The effect is the same in both cases —the violinist dies— and indeed a case could be made that killing him swiftly is more merciful than letting him die slowly.

More here.