From The Scientist:

The world may be at greater risk of infectious diseases that originate in wildlife because people are increasingly encroaching on natural habitats in the tropics to graze livestock and hunt wild animals. Devastating pandemics such as HIV/AIDS, Ebola, and COVID-19, all of which likely originated in wildlife, are reminders of how environmental destruction and infectious disease are intertwined. Tropical deforestation and overhunting are also at the root of global warming and mass species extinction.

The world may be at greater risk of infectious diseases that originate in wildlife because people are increasingly encroaching on natural habitats in the tropics to graze livestock and hunt wild animals. Devastating pandemics such as HIV/AIDS, Ebola, and COVID-19, all of which likely originated in wildlife, are reminders of how environmental destruction and infectious disease are intertwined. Tropical deforestation and overhunting are also at the root of global warming and mass species extinction.

All of these phenomena suggest that what we choose to eat has a fundamental impact on our health and that of the planet. We recently conducted a review of the scientific literature to explore how wildlife-origin diseases, global warming, and mass species extinction are linked to the global food system. Our second objective was to explore reparative actions that governments, NGOs, and each one of us can undertake. From the perspective of individual consumers, the global population needs to shift to diets low in livestock-sourced foods to stem human encroachment on tropical areas of wilderness. Second, there is a need to curb wildmeat demand in tropical cities.

More here.

In 2015, The New York Times Book Review posed the question “Whatever happened to the Novel of Ideas?” to the writers Pankaj Mishra and Benjamin Moser. On the question of “whether philosophical novels have gone the way of the dodo bird,” Mishra answered in the affirmative and—not a writer who shies away from generalizations—charged that the culprit was the MFA program. “America’s postwar creative-writing industry,” Mishra claimed, has “hindered literature from its customary reckoning with the acute problems of the modern epoch” and “boosted instead a cult of private experience.”

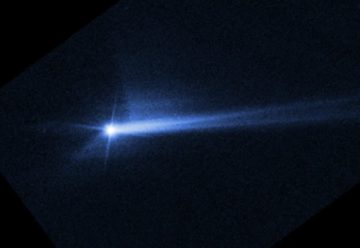

In 2015, The New York Times Book Review posed the question “Whatever happened to the Novel of Ideas?” to the writers Pankaj Mishra and Benjamin Moser. On the question of “whether philosophical novels have gone the way of the dodo bird,” Mishra answered in the affirmative and—not a writer who shies away from generalizations—charged that the culprit was the MFA program. “America’s postwar creative-writing industry,” Mishra claimed, has “hindered literature from its customary reckoning with the acute problems of the modern epoch” and “boosted instead a cult of private experience.” Humans have for the first time proved that they can change the path of a massive rock hurtling through space. NASA has announced that the spacecraft it slammed into an asteroid on 26 September succeeded in altering the space rock’s orbit around another asteroid — with better-than-expected results.

Humans have for the first time proved that they can change the path of a massive rock hurtling through space. NASA has announced that the spacecraft it slammed into an asteroid on 26 September succeeded in altering the space rock’s orbit around another asteroid — with better-than-expected results. A new paper,

A new paper,  As I write this I suddenly realize that All Souls’ Day, November 1, might have been a more timely date for the publication of this article, but alas, that is one of the (very few) inconveniences of not being a religious man. Life is life, however, and certain truths do not always dawn on us in a timely fashion; they come when they come. And in the end, there is so much more to be pondered in November, the month that Herman Melville always associated with melancholy, as he so succinctly expressed it at the beginning of Moby-Dick, through the voice of Ishmael, his narrator who said that “whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul… I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can,” since the sea was his “substitute for pistol and ball.”

As I write this I suddenly realize that All Souls’ Day, November 1, might have been a more timely date for the publication of this article, but alas, that is one of the (very few) inconveniences of not being a religious man. Life is life, however, and certain truths do not always dawn on us in a timely fashion; they come when they come. And in the end, there is so much more to be pondered in November, the month that Herman Melville always associated with melancholy, as he so succinctly expressed it at the beginning of Moby-Dick, through the voice of Ishmael, his narrator who said that “whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul… I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can,” since the sea was his “substitute for pistol and ball.” Filmmaking thrives in plenty of other cities in India, but “Bollywood” has become shorthand for Indian cinema as a whole, and for the thousand or so movies that the country releases annually. For nearly a century, Bollywood has also worn the warm, self-satisfied gloss of being a passion that unifies a country of divisions. Not only are its audiences as mixed as India itself, filmmakers will say, but Bollywood is a place where caste and religion don’t matter. The most piously presented proof of this is the fact that, in a Hindu-majority country, a Muslim man named Shah Rukh Khan has been the supreme box-office star for decades.

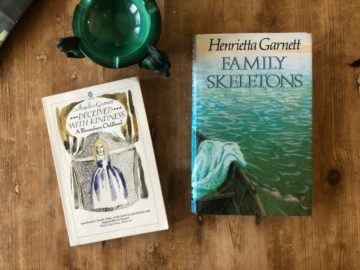

Filmmaking thrives in plenty of other cities in India, but “Bollywood” has become shorthand for Indian cinema as a whole, and for the thousand or so movies that the country releases annually. For nearly a century, Bollywood has also worn the warm, self-satisfied gloss of being a passion that unifies a country of divisions. Not only are its audiences as mixed as India itself, filmmakers will say, but Bollywood is a place where caste and religion don’t matter. The most piously presented proof of this is the fact that, in a Hindu-majority country, a Muslim man named Shah Rukh Khan has been the supreme box-office star for decades. Henrietta Garnett was forty-one when her first and last novel, Family Skeletons, was published in 1986. She knew that her debut, a tragic gothic romance revolving around a complex constellation of family secrets, would face an unusual degree of public scrutiny: Henrietta was English literary royalty, the direct descendant of the Bloomsbury Group on both sides of her family tree. Her father was the novelist David “Bunny” Garnett, author of the James Tait Black Memorial Prize–winning Lady into Fox (1922), a book so highly regarded it was on the British high school syllabus when his daughter was a teenager in the late fifties and early sixties. Henrietta’s mother was Angelica Garnett, née Bell, daughter of Virginia Woolf’s sister, the painter Vanessa Bell. “I had been putting off trying to get anything published,” Henrietta confessed when an interviewer asked about her famous relations, “because I couldn’t help thinking that whatever I did it would never be as good as anything they’ve achieved.” Family Skeletons is a strange and singular creation: melodramatic in plot but elegant in tone, written in a cool and fluent prose that is utterly Henrietta’s own. The novel bears no resemblance to either Bunny’s or Woolf’s fiction; nevertheless, the story does contain more psychological traces of her family’s legacy—namely, of the uniquely disturbing personal dramas that shaped the lives of those who raised her and the public perception of the Bloomsbury Group.

Henrietta Garnett was forty-one when her first and last novel, Family Skeletons, was published in 1986. She knew that her debut, a tragic gothic romance revolving around a complex constellation of family secrets, would face an unusual degree of public scrutiny: Henrietta was English literary royalty, the direct descendant of the Bloomsbury Group on both sides of her family tree. Her father was the novelist David “Bunny” Garnett, author of the James Tait Black Memorial Prize–winning Lady into Fox (1922), a book so highly regarded it was on the British high school syllabus when his daughter was a teenager in the late fifties and early sixties. Henrietta’s mother was Angelica Garnett, née Bell, daughter of Virginia Woolf’s sister, the painter Vanessa Bell. “I had been putting off trying to get anything published,” Henrietta confessed when an interviewer asked about her famous relations, “because I couldn’t help thinking that whatever I did it would never be as good as anything they’ve achieved.” Family Skeletons is a strange and singular creation: melodramatic in plot but elegant in tone, written in a cool and fluent prose that is utterly Henrietta’s own. The novel bears no resemblance to either Bunny’s or Woolf’s fiction; nevertheless, the story does contain more psychological traces of her family’s legacy—namely, of the uniquely disturbing personal dramas that shaped the lives of those who raised her and the public perception of the Bloomsbury Group. If rock and roll has, in fact, become an invalidated form, a “niche product,” encrusted with its political difficulties, and, perhaps, exhausted as a way of thinking about popular music, one of the chief problems, perhaps, is that it has failed to find new ways to use the guitar. Since the high period of guitar innovation—the period in which we had Sonic Youth and their tunings, James “Blood” Ulmer and his unison strings, and the pieces for a hundred guitars of Rhys Chatham and Glenn Branca—there just hasn’t been as much innovation in the guitar as in the years prior (rare exceptions: left-field employment of guitar synthesizers in, e.g., the work of Robert Fripp, or: the beautiful jazz-flavored modulations of Marc Ribot, or: almost everything played by Nels Cline). So it’s striking and, well, thrilling, when a contemporary player appears, rises up from out of the surface noise, and seems to have his ears fixed mightily on the history of the guitar, and with it the potential for rock and roll to speak anew to an audience. Chris Forsyth is one such contemporary player. His point of origin is (arguably) New York punk of the Dolls, Television, Patti Smith group variety, but he also mixes in a kind of jam-oriented approach that would have been somewhat verboten in the orthodox punk days.

If rock and roll has, in fact, become an invalidated form, a “niche product,” encrusted with its political difficulties, and, perhaps, exhausted as a way of thinking about popular music, one of the chief problems, perhaps, is that it has failed to find new ways to use the guitar. Since the high period of guitar innovation—the period in which we had Sonic Youth and their tunings, James “Blood” Ulmer and his unison strings, and the pieces for a hundred guitars of Rhys Chatham and Glenn Branca—there just hasn’t been as much innovation in the guitar as in the years prior (rare exceptions: left-field employment of guitar synthesizers in, e.g., the work of Robert Fripp, or: the beautiful jazz-flavored modulations of Marc Ribot, or: almost everything played by Nels Cline). So it’s striking and, well, thrilling, when a contemporary player appears, rises up from out of the surface noise, and seems to have his ears fixed mightily on the history of the guitar, and with it the potential for rock and roll to speak anew to an audience. Chris Forsyth is one such contemporary player. His point of origin is (arguably) New York punk of the Dolls, Television, Patti Smith group variety, but he also mixes in a kind of jam-oriented approach that would have been somewhat verboten in the orthodox punk days. What, exactly, is David Bentley Hart’s deal? One asks the question in awe. How does he produce so many books—as of this writing, eighteen of them, spanning theology, cultural criticism, and fiction, not counting his translation of the New Testament, his co-translation with John R. Betz of Erich Przywara’s Analogia Entis, his uncollected articles (there must still be a few) and his Substack posts? When did he have time to learn so many languages, that he can refer familiarly to the literatures of Europe, China, Japan, India, and the Americas, and to fine details of theological controversy in several faiths? Where does he find a moment to floss, to do housework, to keep up with his beloved Baltimore Orioles?

What, exactly, is David Bentley Hart’s deal? One asks the question in awe. How does he produce so many books—as of this writing, eighteen of them, spanning theology, cultural criticism, and fiction, not counting his translation of the New Testament, his co-translation with John R. Betz of Erich Przywara’s Analogia Entis, his uncollected articles (there must still be a few) and his Substack posts? When did he have time to learn so many languages, that he can refer familiarly to the literatures of Europe, China, Japan, India, and the Americas, and to fine details of theological controversy in several faiths? Where does he find a moment to floss, to do housework, to keep up with his beloved Baltimore Orioles? My house is isolated, up on the tip of a hill overlooking the Mediterranean Sea, but daybreak sounds rise and reach my window, where I sit reading your book. Someone heckles from a road below to someone else, whom I imagine is trudging uphill. I recognize the Arabic words individually, but strung together, they are senseless to me. I write them down, a small digitalized scribble, on the concluding page of your book, and I mouth them repeatedly, as I do with any new word or phrase in this place, which is also new to me, to cast them in memory. Later, I’ll find someone kind enough to attempt a translation. You would know, Noor, that street calls show for nothing in the online Arabic-to-English dictionary — and that there is a particular kind of angst, a wanting and waiting, at the periphery of a language.

My house is isolated, up on the tip of a hill overlooking the Mediterranean Sea, but daybreak sounds rise and reach my window, where I sit reading your book. Someone heckles from a road below to someone else, whom I imagine is trudging uphill. I recognize the Arabic words individually, but strung together, they are senseless to me. I write them down, a small digitalized scribble, on the concluding page of your book, and I mouth them repeatedly, as I do with any new word or phrase in this place, which is also new to me, to cast them in memory. Later, I’ll find someone kind enough to attempt a translation. You would know, Noor, that street calls show for nothing in the online Arabic-to-English dictionary — and that there is a particular kind of angst, a wanting and waiting, at the periphery of a language. Recently, after a week in which

Recently, after a week in which  Thousands of Egyptians are demanding the repatriation of the Rosetta Stone from the British Museum back to its home country. The iconic artifact, which helped scientists finally decode Egyptian hieroglyphs almost exactly 200 years ago, has been in English hands since Napoleon gave it up – as well as 16 other artifacts – as part of the Treaty of Alexandria in 1801. The latest campaign to reclaim the antiquities has gathered more than 2,500 signatures in an

Thousands of Egyptians are demanding the repatriation of the Rosetta Stone from the British Museum back to its home country. The iconic artifact, which helped scientists finally decode Egyptian hieroglyphs almost exactly 200 years ago, has been in English hands since Napoleon gave it up – as well as 16 other artifacts – as part of the Treaty of Alexandria in 1801. The latest campaign to reclaim the antiquities has gathered more than 2,500 signatures in an  The brain’s lifeline, its network of blood vessels, is like a tree, says Mathieu Pernot, deputy director of the Physics for Medicine Paris Lab. The trunk begins in the neck with the carotid arteries, a pair of broad channels that then split into branches that climb into the various lobes of the brain. These channels fork endlessly into a web of tiny vessels that form a kind of canopy. The narrowest of these vessels are only wide enough for a single red blood cell to pass through, and in one important sense these vessels are akin to the tree’s leaves.

The brain’s lifeline, its network of blood vessels, is like a tree, says Mathieu Pernot, deputy director of the Physics for Medicine Paris Lab. The trunk begins in the neck with the carotid arteries, a pair of broad channels that then split into branches that climb into the various lobes of the brain. These channels fork endlessly into a web of tiny vessels that form a kind of canopy. The narrowest of these vessels are only wide enough for a single red blood cell to pass through, and in one important sense these vessels are akin to the tree’s leaves.