From Phys.Org:

Pain has been long recognized as one of evolution’s most reliable tools to detect the presence of harm and signal that something is wrong—an alert system that tells us to pause and pay attention to our bodies. But what if pain is more than just a mere alarm bell? What if pain is in itself a form of protection? A new study led by researchers at Harvard Medical School suggests that may well be the case in mice. The research, published Oct. 14 in Cell, shows that pain neurons in the mouse gut regulate the presence of protective mucus under normal conditions and stimulate intestinal cells to release more mucus during states of inflammation.

Pain has been long recognized as one of evolution’s most reliable tools to detect the presence of harm and signal that something is wrong—an alert system that tells us to pause and pay attention to our bodies. But what if pain is more than just a mere alarm bell? What if pain is in itself a form of protection? A new study led by researchers at Harvard Medical School suggests that may well be the case in mice. The research, published Oct. 14 in Cell, shows that pain neurons in the mouse gut regulate the presence of protective mucus under normal conditions and stimulate intestinal cells to release more mucus during states of inflammation.

The work details the steps of a complex signaling cascade, showing that pain neurons engage in direct crosstalk with mucus-containing gut cells, known as goblet cells. “It turns out that pain may protect us in more direct ways than its classic job to detect potential harm and dispatch signals to the brain. Our work shows how pain-mediating nerves in the gut talk to nearby epithelial cells that line the intestines,” said study senior investigator Isaac Chiu, associate professor of immunobiology in the Blavatnik Institute at HMS. “This means that the nervous system has a major role in the gut beyond just giving us an unpleasant sensation and that it’s a key player in gut barrier maintenance and a protective mechanism during inflammation.”

More here.

Cihan Tugal in Sidecar:

Cihan Tugal in Sidecar: Samir Sonti and JW Mason in Phenomenal World:

Samir Sonti and JW Mason in Phenomenal World: Ingrid Robeyns in Crooked Timber:

Ingrid Robeyns in Crooked Timber: This is a song that does no favors for anyone, and casts doubt on everything.

This is a song that does no favors for anyone, and casts doubt on everything. In June 1794,

In June 1794,  Analytic philosophers avoided the subject of meaning in life till relatively recently. The standard explanation is that they associated it with the meaning of life question they considered bankrupt. But it’s surely also because the subject conflicts with some of the core tendencies of the analytic tradition. “What gives point to life?” is a sweeping question that invites the synoptic approach associated with continental philosophy, not the divide-and-conquer method favored by Anglo-Americans. The question also wears its angst on its sleeve, making it an awkward fit with the dispassionate mode employed in the mainstream academy.

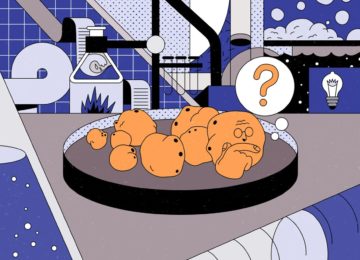

Analytic philosophers avoided the subject of meaning in life till relatively recently. The standard explanation is that they associated it with the meaning of life question they considered bankrupt. But it’s surely also because the subject conflicts with some of the core tendencies of the analytic tradition. “What gives point to life?” is a sweeping question that invites the synoptic approach associated with continental philosophy, not the divide-and-conquer method favored by Anglo-Americans. The question also wears its angst on its sleeve, making it an awkward fit with the dispassionate mode employed in the mainstream academy. In Alysson Muotri’s laboratory, hundreds of miniature human brains, the size of sesame seeds, float in Petri dishes, sparking with electrical activity.

In Alysson Muotri’s laboratory, hundreds of miniature human brains, the size of sesame seeds, float in Petri dishes, sparking with electrical activity. In November of 1660, at Gresham College in London, an invisible college of learned men held their first meeting after 20 years of informal collaboration. They chose their coat of arms: the royal crown’s three lions of England set against a white backdrop. Their motto: “Nullius in verba,” or “take no one’s word for it.” Three years later, they received a charter from King Charles II and became what was and remains the world’s preeminent scientific institution: the Royal Society.

In November of 1660, at Gresham College in London, an invisible college of learned men held their first meeting after 20 years of informal collaboration. They chose their coat of arms: the royal crown’s three lions of England set against a white backdrop. Their motto: “Nullius in verba,” or “take no one’s word for it.” Three years later, they received a charter from King Charles II and became what was and remains the world’s preeminent scientific institution: the Royal Society. Researchers who grew a brain cell culture in a lab claim that they taught the cells to play a version of

Researchers who grew a brain cell culture in a lab claim that they taught the cells to play a version of  The energy crisis incited by Russia’s war in Ukraine has triggered intense debates in many countries about whether the windfall profits that energy companies are now making should be taxed. While this question concerns all companies that produce coal, gas, or oil, the focus currently is on electricity producers. Since a high gas price is driving up electricity prices across the board, suppliers with power plants that use other fuels or renewables can reap extremely high profits. And the immense burden of rising electricity prices on consumers has ratcheted up political pressure to tax “unjustified” profits.

The energy crisis incited by Russia’s war in Ukraine has triggered intense debates in many countries about whether the windfall profits that energy companies are now making should be taxed. While this question concerns all companies that produce coal, gas, or oil, the focus currently is on electricity producers. Since a high gas price is driving up electricity prices across the board, suppliers with power plants that use other fuels or renewables can reap extremely high profits. And the immense burden of rising electricity prices on consumers has ratcheted up political pressure to tax “unjustified” profits. WOLFGANG TILLMANS HAS CREATED an image of contemporary Europe that a lot of people carry around in their heads. Not the Colosseum or the Arc de Triomphe or even the Eiffel Tower, but easyJet, English, Berghain. These keywords are both the technologies and the coordinates of Tillmans’s practice, the atmosphere and infrastructure that support his work, though they are not necessarily visible in his pictures. And yet he has created images—indeed, icons—that are somehow correlates for them, that use these things as scaffolding. I know this is a big claim to make about an artist, given that the profession today no longer has much to do with the way things look. The task of imaging has largely been left to the stylist, the executive, and the influencer. But by leveraging photography’s many lives (as art, as document, as fashion editorial, as reportage, and as publicity), Tillmans has been able to thread the needle through an increasingly vast network of image production, and its sites of display, in order to create a new kind of image—a moving image not simply in the affective sense, but in the circulatory one, too. His images get around, change shape. They are promiscuous. We can call them images in motion.

WOLFGANG TILLMANS HAS CREATED an image of contemporary Europe that a lot of people carry around in their heads. Not the Colosseum or the Arc de Triomphe or even the Eiffel Tower, but easyJet, English, Berghain. These keywords are both the technologies and the coordinates of Tillmans’s practice, the atmosphere and infrastructure that support his work, though they are not necessarily visible in his pictures. And yet he has created images—indeed, icons—that are somehow correlates for them, that use these things as scaffolding. I know this is a big claim to make about an artist, given that the profession today no longer has much to do with the way things look. The task of imaging has largely been left to the stylist, the executive, and the influencer. But by leveraging photography’s many lives (as art, as document, as fashion editorial, as reportage, and as publicity), Tillmans has been able to thread the needle through an increasingly vast network of image production, and its sites of display, in order to create a new kind of image—a moving image not simply in the affective sense, but in the circulatory one, too. His images get around, change shape. They are promiscuous. We can call them images in motion. ONE MAN ALONE

ONE MAN ALONE “You know you’re a nerd when you store DNA in your fridge.”

“You know you’re a nerd when you store DNA in your fridge.”