Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

A Nobel for thinking about long-term growth

Noah Smith at Noahpinion:

Well, it’s time for my annual Economics Nobel post! If you like, you can also check out my posts for 2024, 2023, 2022, and 2021.

Well, it’s time for my annual Economics Nobel post! If you like, you can also check out my posts for 2024, 2023, 2022, and 2021.

Other than the tired old question of whether the Econ Nobel is a “real” Nobel prize,1 there are basically three things to talk about in these posts:

- The research that got the prize

- What the prize says about the economics profession

- What the prize says about politics and policy in the wider world

So first let’s briefly talk about the research. This year’s prize went to Joel Mokyr, for writing about culture and growth, and Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, for making models of technological innovation.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday Poem

Seeking Sleep

Hey — they turned the moon off!

……. gone by my window

………… once too often

I stick my arm out

and get a glassful of dark air.

O to pour

……. the night over my head!

O for a taste

……. of nothing!

……. Everything I’ve lost —

years gone into the past’s

shoes.

Now for the other life!

…………………….. the one

without mistakes.

I finally dream of you.

I’m like a mountain goat

searching for your window

as my crazy hooves

clack along the deserted

streets of town.

by Lou Lipsitz

from Seeking the Hook

Signal Books, 1997

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Water and Carbon Capture for Climate Resilience

Omar Yaghi, a Jordanian-American chemist at the University of California, Berkeley, was awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry today, sharing it with Richard Robson of the University of Melbourne, Australia, and Susumu Kitagawa of Kyoto University, Japan. The scientists were cited for creating “molecular constructions with large spaces through which gases and other chemicals can flow. These constructions, metal-organic frameworks, can be used to harvest water from desert air, capture carbon dioxide, store toxic gases or catalyze chemical reactions.”

More here.

The World’s First Climate Tipping Point Has Been Crossed, Scientists Say

Simmone Shah in Time Magazine:

The exact moment when Earth will reach its tipping points—moments at which human-induced climate change will trigger irreversible planetary changes—has long been a source of debate for scientists. But they might be closer than we think. A report published today says that the Earth has passed its first climate tipping point. The second “Global Tipping Points” report published by the University of Exeter found that warm-water coral reefs are passing their tipping point. Rising ocean temperatures, acidification, overfishing, and pollution are combining to cause coral bleaching and mortality, meaning that a large number of coral reefs will be lost unless the global temperature returns towards 1°C warming or below.

The exact moment when Earth will reach its tipping points—moments at which human-induced climate change will trigger irreversible planetary changes—has long been a source of debate for scientists. But they might be closer than we think. A report published today says that the Earth has passed its first climate tipping point. The second “Global Tipping Points” report published by the University of Exeter found that warm-water coral reefs are passing their tipping point. Rising ocean temperatures, acidification, overfishing, and pollution are combining to cause coral bleaching and mortality, meaning that a large number of coral reefs will be lost unless the global temperature returns towards 1°C warming or below.

“We’re in a new climate reality,” said Tim Lenton, founding director at the Global Systems Institute at the University of Exeter, who led the report. “We’ve crossed a tipping point in the climate system, and we’re now sure we’re going to carry on through 1.5°C of global warming above the prior industrial level, and that’s going to put us in the danger zone for crossing more climate tipping points.” The planet is predicted to cross the 1.5°C threshold within the next 5 years, according to a report from the World Meteorological Organization. Once that threshold is reached, the planet will see more frequent and intense extreme weather and strains on food production and water access—impacts many nations vulnerable to climate change are already seeing.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Monday, October 13, 2025

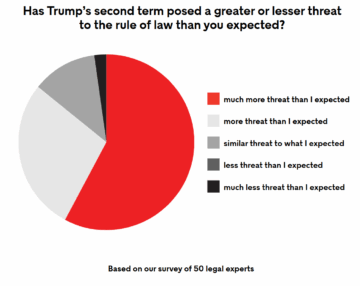

The NY Times: We Asked 50 Legal Experts About the Trump Presidency

Emily Bazelon in the New York Times:

Last year, in the months before the 2024 presidential election, the magazine surveyed 50 members of what might be called the Washington legal establishment about their expectations for the Justice Department and the rule of law if Donald Trump were re-elected. The group was evenly split between Democrats and Republicans. They had worked as high-level officials for every president since Ronald Reagan.

Last year, in the months before the 2024 presidential election, the magazine surveyed 50 members of what might be called the Washington legal establishment about their expectations for the Justice Department and the rule of law if Donald Trump were re-elected. The group was evenly split between Democrats and Republicans. They had worked as high-level officials for every president since Ronald Reagan.

A majority of our respondents told us they were alarmed about a potential second Trump term given the strain he put on the legal system the first time around. But several dissenters countered that those fears were overblown. One former Trump official predicted that the Justice Department would be led by lawyers like those in the first term — elite, conservative and independent. “It’s hard to be a bad-faith actor at the Justice Department,” he said at the time. “And the president likes the Ivy League and Supreme Court clerkships on résumés.”

Eight months into his second term, Trump has taken a wrecking ball to those beliefs. “What’s happening is anathema to everything we’ve ever stood for in the Department of Justice,” said another former official who served in both Democratic and Republican administrations, including Trump’s first term.

We recently returned to our group with a new survey and follow-up interviews about Trump’s impact on the rule of law since retaking office. The responses captured almost universal fear and anguish over the transformation of the Justice Department into a tool of the White House.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A Look into the Iberian Blackout

Deric Tilson at The Ecomodernist:

On April 28, 2025, at 12:33:24 CET, a blackout encompassed Spain, Portugal, and parts of southwest France, leaving over 50 million people without power. The loss of electricity cost Spain an estimated $1.82 billion in economic output and damages. When the Iberian grid collapsed, people who were going about their day moments before were now stuck in elevators, food in freezers and refrigerators began to thaw or spoil, and non-urgent medical needs were delayed as hospitals dealt with scarce backup power supplies.

On April 28, 2025, at 12:33:24 CET, a blackout encompassed Spain, Portugal, and parts of southwest France, leaving over 50 million people without power. The loss of electricity cost Spain an estimated $1.82 billion in economic output and damages. When the Iberian grid collapsed, people who were going about their day moments before were now stuck in elevators, food in freezers and refrigerators began to thaw or spoil, and non-urgent medical needs were delayed as hospitals dealt with scarce backup power supplies.

Quickly, pundits, experts, and posters on social media descended on the details of the blackout, grabbing what information they could, and spewing hot takes: “Solar is to blame.” “Why did the nuclear power plants go offline?” “Green energies and renewables did this.” “Aha, nuclear plants were in planned outage.” Schadenfreude abounds when systems begin to break, especially when aspects of those systems are politically charged.

Fifteen hours later, the transmission grids of Spain and Portugal were restored to full operation. Electrons once again flowed to people’s homes, charging their phones, illuminating their rooms, cooling their food, and providing them with modern comforts. The question of how the blackout happened remained.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Social engineering, malware, and the future of cybersecurity in AI

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

What Japan Taught Me About American Trains: Amtrak made an airplane without wings

Quico Toro at Persuasion:

Begin with the station layout. In New York, you wait for your train not on the platform, but in a ticketed waiting room, where you watch for gate announcements that explicitly mimic what you get at an airport.

Passengers then schlep to line up at the one escalator leading down to the tracks. This chokepoint is entirely of Amtrak’s choosing; nothing about the technology itself necessitates it. Airplanes have a single point of entry; lining up to board is inevitable. Trains obviate the need for this, but on the Acela you have to line up anyway. Before you’ve even boarded the train, Amtrak has already nullified one of its best advantages.

Another way trains are different from airplanes is that they run on tracks, so they don’t experience air turbulence. Without turbulence, luggage bins can be uncovered (as they are on the Shinkansen), which makes them much more visible and much more useful.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

An AI Council Just Aced the US Medical Licensing Exam

Edd Gent in Singularity Hub:

Despite their usefulness, large language models still have a reliability problem. A new study shows that a team of AIs working together can score up to 97 percent on US medical licensing exams, outperforming any single AI. While recent progress in large language models (LLMs) has led to systems capable of passing professional and academic tests, their performance remains inconsistent. They’re still prone to hallucinations—plausible sounding but incorrect statements—which has limited their use in high-stakes area like medicine and finance.

Despite their usefulness, large language models still have a reliability problem. A new study shows that a team of AIs working together can score up to 97 percent on US medical licensing exams, outperforming any single AI. While recent progress in large language models (LLMs) has led to systems capable of passing professional and academic tests, their performance remains inconsistent. They’re still prone to hallucinations—plausible sounding but incorrect statements—which has limited their use in high-stakes area like medicine and finance.

Nonetheless, LLMs have scored impressive results on medical exams, suggesting the technology could be useful in this area if their inconsistencies can be controlled. Now, researchers have shown that getting a “council” of five AI models to deliberate over their answers rather than working alone can lead to record-breaking scores in the US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE). “Our study shows that when multiple AIs deliberate together, they achieve the highest-ever performance on medical licensing exams,” Yahya Shaikh, from John Hopkins University, said in a press release. “This demonstrates the power of collaboration and dialogue between AI systems to reach more accurate and reliable answers.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Unintended chemotherapy consequences can drive drug resistance

From Nature:

The mission with cancer therapy is clear: eradicate as many tumour cells as possible. Traditional chemotherapy remains a mainstay, where patients are dosed with potent compounds that disrupt essential cellular functions, preventing tumour cells from proliferating and ultimately forcing them to self-destruct. However, new findings1 from a team led by Hongbo Gao and Keith Syson Chan at the Houston Methodist Academic Institute suggest that this approach might also release signals that promote drug resistance, which makes it harder to eliminate the tumour in the long run.

The mission with cancer therapy is clear: eradicate as many tumour cells as possible. Traditional chemotherapy remains a mainstay, where patients are dosed with potent compounds that disrupt essential cellular functions, preventing tumour cells from proliferating and ultimately forcing them to self-destruct. However, new findings1 from a team led by Hongbo Gao and Keith Syson Chan at the Houston Methodist Academic Institute suggest that this approach might also release signals that promote drug resistance, which makes it harder to eliminate the tumour in the long run.

Chan first became aware of this possibility a decade ago2. “We and others showed that the type of cell death the cancer cell undergoes also determines the therapeutic efficacy,” he says. His group demonstrated that, in some scenarios, chemo-induced cell death can lead to the dissemination of growth factors and other molecules, enabling surviving resistant cells to subsequently thrive and proliferate even during ongoing treatment. In their latest work, Chan and Gao focused on a mechanism known as pyroptosis, wherein tumour cells perish in a manner that leads to release of pro-inflammatory signals. This is generally thought to be a good outcome in the context of immunotherapy, as such an environment can amplify a patient’s anti-tumour immune response and put cancer cells on the defensive.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday, October 12, 2025

Reclaiming Europe’s Digital Sovereignty

Francesca Bria in Noema:

Geopolitical power once flowed through armies and treaties, but today it courses through silicon wafers, server farms and algorithmic systems. These invisible digital infrastructures and architectures shape every aspect of modern life. “The Stack” — interlocking layers of hardware, software, networks and data — has become the operating system of modern political and economic power.

The global race to control the Stack defines the emerging world order. The United States consolidates its dominance through initiatives like Stargate, which fuses AI development directly to proprietary chips and hyperscale data centers, creating insurmountable barriers to competition. China advances through systematic industrial policy and its Digital Silk Road, achieving unprecedented integration from chip design to AI deployment across Asia and beyond. These are deliberate strategies of technological imperialism.

Europe occupies a paradoxical position: a regulatory leader but infrastructurally dependent. We Europeans have set global standards through GDPR and the AI Act. Our research institutions remain world-class. Yet just 4% of global cloud infrastructure is European-owned. European governments, businesses and citizens depend entirely on systems controlled by Amazon, Microsoft and Google — companies subject to the U.S. CLOUD Act’s extraterritorial surveillance requirements. When we use “our” digital services, we’re actually using American infrastructure governed by American law for American interests.

This dependency isn’t abstract — it’s existential.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Defeated by reality

Branko Milanovic over at his substack Global Inequality and More 3.0:

Why did neoliberalism, in its domestic and international components, fail? I ask this question, in much more detail than I can do it in a short essay here, in my forthcoming The Great Global Transformation: National Market Liberalism in a Multipolar World. I am asking it for personal reasons too: some of my best friends are neoliberal. It was a generational project of Western baby-boomers which later got adopted by others, from Eastern Europe like myself, and Latin American and African elites. When nowadays I meet my aging baby-boomer friends, still displaying an almost undiminished zeal for neoliberalism, they seem like the ideological escapees from a world that has disappeared long time ago. They are not from Venus or Mars; they are from the Titanic.

When I say that neoliberalism was defeated I do not mean than it was intellectually defeated in the sense than there is an alternative ready-made project waiting in the wings to replace it. No: like communism, neoliberalism was defeated by reality. Real world simply refused to behave the way that liberals thought it should.

We need first to acknowledge that the project had many attractive sides. It was ideologically and generationally linked to the rebellious generation of the 1960s, so its pedigree was non-conformist. It promoted racial, gender and sexual equality. By its emphasis on globalization, it has to be credited by helping along the greatest reduction in global poverty ever and for helping many countries find the path to prosperity.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Lea Ypi’s Reckoning With Family and the Legacy of Revolution

Lily Lynch in Jacobin:

Earlier this summer, an Albanian friend in Istanbul told me a story. During the Cold War, Albanians fleeing Enver Hoxha’s People’s Socialist Republic of Albania would cross Lake Shkodra in boats. If they were lucky, and they weren’t captured by government patrol, drowned, or shot by guards, they would disembark on the shores of my friend’s lakeside village in Montenegro, then part of Yugoslavia. The two countries occupied diametrically opposed poles in the communist world: Albania was the most isolated, while Yugoslavia — separate from the Eastern Bloc since Josip Broz Tito’s split with Joseph Stalin in 1948 — was the most open. (The red Yugoslav passport, the source of much boomer Yugonostalgia, allowed visa-free travel to more than a hundred countries.)

Albania’s litany of eccentricities is well known. In the words of one observer, the world’s first officially atheist state banned “bearded visitors, Americans, and God.” Fleeing the country was considered treason; those caught were lucky to get away with hard labor. As remote as it all sounds today, my friend’s story about the boats bound for Montenegro made me think of contemporary headline news: the recent wave of small-boat migration of Albanians to the United Kingdom.

In 2022 alone, 12,300 Albanians crossed the English Channel aboard rickety rubber dinghies, risking death to get to Britain’s shores. Why was it that I didn’t immediately associate that journey with a cruel ideology? Certainly global capitalism and inequality played a big part. But why don’t we blame them in the same way we do the autarkic communism of Uncle Enver’s Albania?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

When celebrities break up, everyone’s a forensic expert

From The Washington Post:

The clues that Nicole Kidman and Keith Urban’s nearly 20-year marriage was cracking up were everywhere, according to an internet full of sleuths.

The clues that Nicole Kidman and Keith Urban’s nearly 20-year marriage was cracking up were everywhere, according to an internet full of sleuths.

You could tell when Urban refused to talk about the actress in a newspaper interview last September, a full year before Kidman filed to divorce him. Or that time he changed a love song’s lyrics mid-concert, swapping “baby” for “Maggie” in a shout-out to his guitarist. Maybe it was Kidman’s sexy scenes in “Babygirl” that splintered their union. Or maybe it was Urban’s feet. “You can tell everything about a short man by his shoes,” a TikToker declared, analyzing a red-carpet photo of the couple, in which Kidman towered over her husband despite his chunky platform boots. “Keith Urban’s insecurity in relationship to Nicole’s starts from the bottom.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday Poem

Ice Dance

jason said it was all just light from windows

just light that had fallen and had stained the ground,

ground which would go away said jason

stains on the ground through windows

just light he said

…………………………………… just jason, standing

with his government name and identification badge

and memorized numerals and credentials he did not give

but allowed to swirl as suggestions,

proof in the negative sticking to him

like any other stain are you who

you say you are

……………………….. jason,

……………….. now nameless, behind the mask

face now jasonless,

………………………………………….. still with hands

former flipper of burgers and player of ball

now catch ave marias, detain them in the dugout

of some sunny afternoon in Chicago

jason jayson jay jameson joshua john

john jean juan johnny jack jason we are glued

to you like a dancer on ice, gliding on

around the ring of the rest of our life

now extended, watching you receive

and enact an increasingly worrying set

of orders and inside of us another arena,

with equal chill, where we stretch, imagine

running, the inevitable fall, imagine doing

the dance, either part, the silence from the risers

of uncalled upon names, mute power

of all those lap-held hands.

by Ingrid Jacobsen

from Rattle Magazine

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Kafka Challenge: Translating the Inimitable

Paul Reitter in The Hedgehog Review:

When I taught German in graduate school back in the late 1990s, my fellow instructors and I often used a line from Franz Kafka’s novel The Trial to illustrate a point about grammar that was also a point about untranslatability.1 In German, as in English, the regular subjunctive form goes mainly with wishes, counterfactual conditions, statements, and questions, as well as with polite requests. But the German form has an additional function: It can mark speculation—or, really, ambiguity—in a way that’s hard to match in English. Kafka’s line evokes a vivid sense of this gap, which, in the first place, is why we turned to it here. However, we had further reasons for doing that, starting with the fact that untranslatability is one of Kafka’s great themes.

When I taught German in graduate school back in the late 1990s, my fellow instructors and I often used a line from Franz Kafka’s novel The Trial to illustrate a point about grammar that was also a point about untranslatability.1 In German, as in English, the regular subjunctive form goes mainly with wishes, counterfactual conditions, statements, and questions, as well as with polite requests. But the German form has an additional function: It can mark speculation—or, really, ambiguity—in a way that’s hard to match in English. Kafka’s line evokes a vivid sense of this gap, which, in the first place, is why we turned to it here. However, we had further reasons for doing that, starting with the fact that untranslatability is one of Kafka’s great themes.

Untranslatability is also one of George Steiner’s great themes—and one of his central concerns in his commentary on Kafka. It would be hard to think of a literary scholar or critic who has done more to draw attention to this aspect of Kafka’s work, to reveal it as a guiding principle. In his essay “K,” for instance, Steiner cites, at length, a previously underexamined diary entry in which Kafka discusses how for him the German words Mutter and Vater fail “to approximate to” Jewish mothers and fathers. Kafka suggests that his psychic life was shaped by this linguistic misalignment; as a result of it, he “did not always love” his mother as “she deserved” to be loved and as he was capable of loving her. Steiner goes on to read “The Burrow,” one of Kafka’s last stories, as “a parable” of “the artist unhoused in his language,” a point he makes to explain nothing less than “the fantastic nakedness and economy” of Kafka’s prose.2

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, October 10, 2025

I’ve Gone to Look for America

Masha Hamilton at Atavist:

The sky is dark. The highway hums beneath our tires. We’ve covered a lot of miles today, and the night is pressing us off the road, toward a Virginia rest stop where, years ago, a man was murdered in a bathroom. I want to see the door he pushed open, stand where he stood, feel how quickly ordinary moments can turn.

The sky is dark. The highway hums beneath our tires. We’ve covered a lot of miles today, and the night is pressing us off the road, toward a Virginia rest stop where, years ago, a man was murdered in a bathroom. I want to see the door he pushed open, stand where he stood, feel how quickly ordinary moments can turn.

But more than anything right now, I want to stop. Stretch out in the back of Cheney’s car, let the wash of highway noise lull us for a few hours. It’s been another long day of catching strangers mid-journey, asking one personal question and then another.

We’re on the road, my oldest son and I, traveling nearly 2,000 miles on Interstate 95 from Miami to Maine, and pausing at virtually every rest stop. Our project is simple and vast at once: to ask fellow travelers where they’re headed, and where they think America is going too. I take notes. Cheney takes photos.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

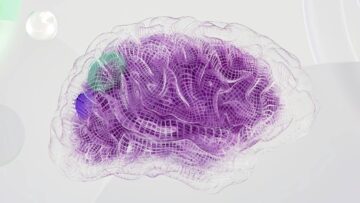

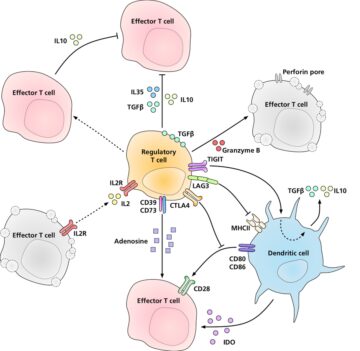

How does your immune system stay balanced? A Nobel Prize-winning answer

Aimee Pugh Bernard in The Conversation:

Every day, your immune system performs a delicate balancing act, defending you from thousands of pathogens that cause disease while sparing your body’s own healthy cells. This careful equilibrium is so seamless that most people don’t think about it until something goes wrong.

Every day, your immune system performs a delicate balancing act, defending you from thousands of pathogens that cause disease while sparing your body’s own healthy cells. This careful equilibrium is so seamless that most people don’t think about it until something goes wrong.

Autoimmune diseases such as Type 1 diabetes, lupus and rheumatoid arthritis are stark reminders of what happens when the immune system mistakes your own cells as threats it needs to attack. But how does your immune system distinguish between “self” and “nonself”?

The 2025 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine honors three scientists – Shimon Sakaguchi, Mary Brunkow and Fred Ramsdell – whose groundbreaking discoveries revealed how your immune system maintains this delicate balance. Their work on two key components of immune tolerance – regulatory T cells and the FOXP3 gene – transformed how researchers like me understand the immune system, opening new doors for treating autoimmune diseases and cancer.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Iain McGilchrist – Idealism: Arguing Pro and Con

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.