Pranab Bardhan at his own Substack:

I had a visceral distaste for the country’s imperial hegemony and its support of oppressive regimes all over the world in the name of fighting the Cold War. The ongoing Vietnam War was an obvious irritant. At the same time, I knew that in the world of new ideas, entrepreneurial innovations and academic excellence, American pre-eminence was undeniable.

I had a visceral distaste for the country’s imperial hegemony and its support of oppressive regimes all over the world in the name of fighting the Cold War. The ongoing Vietnam War was an obvious irritant. At the same time, I knew that in the world of new ideas, entrepreneurial innovations and academic excellence, American pre-eminence was undeniable.

In fact, coming from an extremely hierarchical Indian society and then from the class snobbery that pervades in England, in some sense the American social scene was a bit of fresh air for me, somewhat contrary to what I had expected (and guessed from reading about the country’s dark history of racial oppression and discrimination). At MIT where Joe Stiglitz and I were hired as young economics assistant professors at the same time, our offices were close together, and both Joe and I used to work until quite late. Late evenings the janitors (mostly black) would come to sweep the floors and clean the bins and the toilets. Sometimes they’d sit down in our rooms and chat with us about the latest in sports, weather or politics. To Joe, this was routine; he did not realize how pleasantly out of the ordinary it was for me, coming from India. To this day in India, I have never seen a sweeper or a toilet cleaner daring to sit and chat with professors (or with students, for that matter). So that was a refreshing experience.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

THE PATERNITY OF Hicks McTaggart—defender of dames, dodger of bombs, twirler of spaghetti, the amiable behemoth hero of Thomas Pynchon’s Shadow Ticket who prowls the streets of Depression-era Milwaukee—is a question his author leaves open. His mother, Grace, and her sister, Peony, “grew up in the Driftless Area, a patch of Wisconsin never visited by glaciers, so that its terrain tends to be a little less flat and ground down than the rest of the state, free of the rubble, known as drift, that glaciers leave behind.” (Despite its charming name, the Driftless Area is a real place, not a Pynchonian invention.) Once old enough to hitchhike (“Soon as they could figure out how to bring their thumbs out of their mouths and into the wind”), Grace and Peony started consorting with circus performers wintering in Baraboo, a town at the Driftless Area’s northeastern edge, before making their way to Milwaukee to take ordinary jobs and marry ordinary men. Grace’s marriage to Eddie McTaggart was interrupted by the discovery of her ongoing affair with Max, a German elephant trainer back in Baraboo. Eddie skipped town and headed west, never to be heard from again. Of Max we are told: “When other boys got sentimental they talked about all the children you were going to have, with Max it was more likely to be elephants.”

THE PATERNITY OF Hicks McTaggart—defender of dames, dodger of bombs, twirler of spaghetti, the amiable behemoth hero of Thomas Pynchon’s Shadow Ticket who prowls the streets of Depression-era Milwaukee—is a question his author leaves open. His mother, Grace, and her sister, Peony, “grew up in the Driftless Area, a patch of Wisconsin never visited by glaciers, so that its terrain tends to be a little less flat and ground down than the rest of the state, free of the rubble, known as drift, that glaciers leave behind.” (Despite its charming name, the Driftless Area is a real place, not a Pynchonian invention.) Once old enough to hitchhike (“Soon as they could figure out how to bring their thumbs out of their mouths and into the wind”), Grace and Peony started consorting with circus performers wintering in Baraboo, a town at the Driftless Area’s northeastern edge, before making their way to Milwaukee to take ordinary jobs and marry ordinary men. Grace’s marriage to Eddie McTaggart was interrupted by the discovery of her ongoing affair with Max, a German elephant trainer back in Baraboo. Eddie skipped town and headed west, never to be heard from again. Of Max we are told: “When other boys got sentimental they talked about all the children you were going to have, with Max it was more likely to be elephants.” T

T Despite the fact nearly no one knows her true identity, Elena Ferrante needs perhaps no introduction. The prolific and reclusive Italian writer has been writing since 1992, but reached international fame with My Brilliant Friend, the first of the Neapolitan Quartet of novels. It was the skillful hand of translator Ann Goldstein who helped introduce the novels to an English-reading audience. Though she was an integral part of one of the most popular works of fiction in the 21st century, Goldstein tells me she became a translator “accidentally,” after having studied Italian while working in the copy editing department of the New Yorker.

Despite the fact nearly no one knows her true identity, Elena Ferrante needs perhaps no introduction. The prolific and reclusive Italian writer has been writing since 1992, but reached international fame with My Brilliant Friend, the first of the Neapolitan Quartet of novels. It was the skillful hand of translator Ann Goldstein who helped introduce the novels to an English-reading audience. Though she was an integral part of one of the most popular works of fiction in the 21st century, Goldstein tells me she became a translator “accidentally,” after having studied Italian while working in the copy editing department of the New Yorker. Are AIs capable of murder?

Are AIs capable of murder? As Jeff Chang puts it in “Water Mirror Echo,” his exuberant new book about Lee as both a celebrity and an Asian American, the restless actor oscillated between “follow-the-flow Zen surrender” and “sunset-chasing American ambition.” Chang gets his title from a portion of a Taoist classic, “The Liezi,” that Lee found striking enough to transcribe:

As Jeff Chang puts it in “Water Mirror Echo,” his exuberant new book about Lee as both a celebrity and an Asian American, the restless actor oscillated between “follow-the-flow Zen surrender” and “sunset-chasing American ambition.” Chang gets his title from a portion of a Taoist classic, “The Liezi,” that Lee found striking enough to transcribe: AI systems’ mastery of language may or may not portend a future of superintelligent AI minds, but it already provides a proof of concept for a revolution in gene editing. And though such a revolution promises to unlock transformative medical advancements, it also brings longstanding bioethical dilemmas to the fore: Should people of means be able to hardwire physical or cognitive advantages into their genomes, or their children’s? Where is the line between medical therapy and dehumanizing enhancements?

AI systems’ mastery of language may or may not portend a future of superintelligent AI minds, but it already provides a proof of concept for a revolution in gene editing. And though such a revolution promises to unlock transformative medical advancements, it also brings longstanding bioethical dilemmas to the fore: Should people of means be able to hardwire physical or cognitive advantages into their genomes, or their children’s? Where is the line between medical therapy and dehumanizing enhancements? W

W A

A According to the philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, the 20th century’s form of life also began with the air. Sloterdijk puts the moment at 6 p.m. on April 22, 1915, near Ypres, when a German regiment under the command of Col. Max Peterson unleashed chlorine gas in warfare for the first time. Previously, violence in war had been directed at the human body; this attack targeted the “living organism’s immersion in a breathable milieu,” as Sloterdijk writes in “

According to the philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, the 20th century’s form of life also began with the air. Sloterdijk puts the moment at 6 p.m. on April 22, 1915, near Ypres, when a German regiment under the command of Col. Max Peterson unleashed chlorine gas in warfare for the first time. Previously, violence in war had been directed at the human body; this attack targeted the “living organism’s immersion in a breathable milieu,” as Sloterdijk writes in “ The drug discovery and development landscape is plagued by inefficiency, risk and astronomical cost. Clinical success rates languish below 10%, convoluted in- and out-licensing workflows erode precious patent life, and industry estimates suggest that biopharma companies write off some $15 billion every year on deprioritized candidates. At the same time, more than 90% of oncology drugs—and a significant proportion of all therapeutics—will lose patent exclusivity within the next five years, creating a looming innovation shortfall. Partex is here to bridge that gap. As the world’s largest artificial intelligence (AI)-driven drug-asset manager, Partex supercharges pipelines, resurrects shelved compounds and slashes development time to clinic—revolutionizing discovery and development at every step.

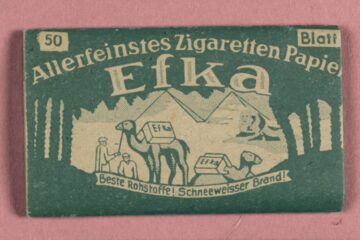

The drug discovery and development landscape is plagued by inefficiency, risk and astronomical cost. Clinical success rates languish below 10%, convoluted in- and out-licensing workflows erode precious patent life, and industry estimates suggest that biopharma companies write off some $15 billion every year on deprioritized candidates. At the same time, more than 90% of oncology drugs—and a significant proportion of all therapeutics—will lose patent exclusivity within the next five years, creating a looming innovation shortfall. Partex is here to bridge that gap. As the world’s largest artificial intelligence (AI)-driven drug-asset manager, Partex supercharges pipelines, resurrects shelved compounds and slashes development time to clinic—revolutionizing discovery and development at every step. Open one of the drawers in a collections cabinet at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and you’ll find a small booklet of Efka cigarette papers. The papers are part of a broader story the museum tells about Nazism, corporate collaboration, and wartime propaganda.

Open one of the drawers in a collections cabinet at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and you’ll find a small booklet of Efka cigarette papers. The papers are part of a broader story the museum tells about Nazism, corporate collaboration, and wartime propaganda. Italy is not always the salvation of English-speaking people—but it does often seem that way. In film, in literature, in food, it’s the place where you go to find yourself. The real you, the one whose blazing depths have been obscured by the cold crust of convention. In The Enchanted April—the 1922 bestseller that turned Positano into a tourist destination—Elizabeth von Arnim suggested that the Mediterranean climate could burn off the impurities of the English soul, as if by a kind of Italian alchemy. English travelers from Byron to E. M. Forster advanced a similar sort of travel magic as a means for getting in touch with one’s soul. Keats, wracked with tuberculosis, went to Italy hoping to save his life.

Italy is not always the salvation of English-speaking people—but it does often seem that way. In film, in literature, in food, it’s the place where you go to find yourself. The real you, the one whose blazing depths have been obscured by the cold crust of convention. In The Enchanted April—the 1922 bestseller that turned Positano into a tourist destination—Elizabeth von Arnim suggested that the Mediterranean climate could burn off the impurities of the English soul, as if by a kind of Italian alchemy. English travelers from Byron to E. M. Forster advanced a similar sort of travel magic as a means for getting in touch with one’s soul. Keats, wracked with tuberculosis, went to Italy hoping to save his life. Super Agers, by clinician Eric Topol, has just been published, but it was almost surreal for me as a US scientist to read the book now, with its optimistic take on the state of the medical field. Despite their extreme promise, many of the lines of research that Topol describes have been subject to

Super Agers, by clinician Eric Topol, has just been published, but it was almost surreal for me as a US scientist to read the book now, with its optimistic take on the state of the medical field. Despite their extreme promise, many of the lines of research that Topol describes have been subject to  I meet a lot of people who don’t like their jobs, and when I ask them what they’d rather do instead, about 75% say something like, “Oh, I dunno, I’d really love to run a little coffee shop.” If I’m feeling mischievous that day, I ask them one question: “Where would you get the coffee beans?”

I meet a lot of people who don’t like their jobs, and when I ask them what they’d rather do instead, about 75% say something like, “Oh, I dunno, I’d really love to run a little coffee shop.” If I’m feeling mischievous that day, I ask them one question: “Where would you get the coffee beans?”