Steve Nadis in Quanta:

In 1939, upon arriving late to his statistics course at the University of California, Berkeley, George Dantzig — a first-year graduate student — copied two problems off the blackboard, thinking they were a homework assignment. He found the homework “harder to do than usual,” he would later recount, and apologized to the professor for taking some extra days to complete it. A few weeks later, his professor told him that he had solved two famous open problems in statistics. Dantzig’s work would provide the basis for his doctoral dissertation and, decades later, inspiration for the film Good Will Hunting.

In 1939, upon arriving late to his statistics course at the University of California, Berkeley, George Dantzig — a first-year graduate student — copied two problems off the blackboard, thinking they were a homework assignment. He found the homework “harder to do than usual,” he would later recount, and apologized to the professor for taking some extra days to complete it. A few weeks later, his professor told him that he had solved two famous open problems in statistics. Dantzig’s work would provide the basis for his doctoral dissertation and, decades later, inspiration for the film Good Will Hunting.

Dantzig received his doctorate in 1946, just after World War II, and he soon became a mathematical adviser to the newly formed U.S. Air Force. As with all modern wars, World War II’s outcome depended on the prudent allocation of limited resources. But unlike previous wars, this conflict was truly global in scale, and it was won in large part through sheer industrial might. The U.S. could simply produce more tanks, aircraft carriers and bombers than its enemies. Knowing this, the military was intensely interested in optimization problems — that is, how to strategically allocate limited resources in situations that could involve hundreds or thousands of variables.

The Air Force tasked Dantzig with figuring out new ways to solve optimization problems such as these. In response, he invented the simplex method, an algorithm that drew on some of the mathematical techniques he had developed while solving his blackboard problems almost a decade before.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

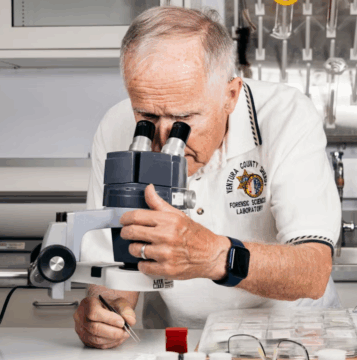

Trace evidence analysis is the most versatile of the crime scene disciplines, requiring a specialist to be ready for whatever comes through the door. Officially, a trace analyst handles anything that doesn’t fit into the other standard crime lab departments, which tend to include body fluids (also known as serology), fingerprints, and ballistics. In reality, it can include analyzing an absurd variety of materials. It could be flame accelerant, explosives, cosmetics, carpet fibers, tree bark, hairs, shoe prints, clothing, dirt, glass fragments, tape, glue, and, yes, glitter.

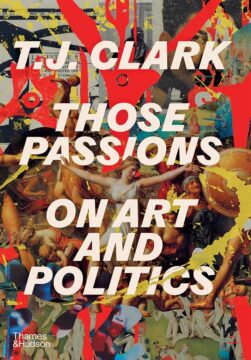

Trace evidence analysis is the most versatile of the crime scene disciplines, requiring a specialist to be ready for whatever comes through the door. Officially, a trace analyst handles anything that doesn’t fit into the other standard crime lab departments, which tend to include body fluids (also known as serology), fingerprints, and ballistics. In reality, it can include analyzing an absurd variety of materials. It could be flame accelerant, explosives, cosmetics, carpet fibers, tree bark, hairs, shoe prints, clothing, dirt, glass fragments, tape, glue, and, yes, glitter. What made Clark’s appearance in the guise of an art critic an event was not just his already existing eminence as an art historian. Nor was it the fact that Clark is one of the rare art historians who has forged a style for his writing, by which I mean that he is always himself, and always recognizably himself, in his prose. Rather, it was that he was contravening the conventional division of labor within art writing: Old art is the subject of history, new art is the subject of criticism. What was thrilling about Clark’s new enterprise was that he was writing about artists such as Bosch and Velázquez not as a historian but as a critic—and yet was doing so with a historian’s erudition and authority rather than with the more approachable fluency with which a belletristic critic such as Jed Perl or Peter Schjeldahl might do so. He was, in a sense, disproving (or at least providing an exception to) Marcel Duchamp’s cynical remark that “after a work has lived almost the life of a man…comes a period when that work of art, if it is still looked at by onlookers, is put in a museum. A new generation decides that it is all right. And those two ways of judging a work of art”—before and after it is consecrated by the museum—“certainly don’t have anything in common.” Clark, by contrast, was treating the art of the past as what it is or should be, something alive and challenging in the present, and not just as what it also is, an artifact.

What made Clark’s appearance in the guise of an art critic an event was not just his already existing eminence as an art historian. Nor was it the fact that Clark is one of the rare art historians who has forged a style for his writing, by which I mean that he is always himself, and always recognizably himself, in his prose. Rather, it was that he was contravening the conventional division of labor within art writing: Old art is the subject of history, new art is the subject of criticism. What was thrilling about Clark’s new enterprise was that he was writing about artists such as Bosch and Velázquez not as a historian but as a critic—and yet was doing so with a historian’s erudition and authority rather than with the more approachable fluency with which a belletristic critic such as Jed Perl or Peter Schjeldahl might do so. He was, in a sense, disproving (or at least providing an exception to) Marcel Duchamp’s cynical remark that “after a work has lived almost the life of a man…comes a period when that work of art, if it is still looked at by onlookers, is put in a museum. A new generation decides that it is all right. And those two ways of judging a work of art”—before and after it is consecrated by the museum—“certainly don’t have anything in common.” Clark, by contrast, was treating the art of the past as what it is or should be, something alive and challenging in the present, and not just as what it also is, an artifact. L

L Michael Hurley,

Michael Hurley, How can we stay happy in an age gone mad? It often feels as though all is unstable at the moment. Uncertainty dominates the economy. Our politics and planet are a mess. Scientific experts and government workers have been cast aside.

How can we stay happy in an age gone mad? It often feels as though all is unstable at the moment. Uncertainty dominates the economy. Our politics and planet are a mess. Scientific experts and government workers have been cast aside.  Imagine that you are a cook, and you just made a cake in your kitchen. You’ve made a delicious cake, and you’d like to start a business making 1,000 of them a day. So you replicate your kitchen 1,000 times over—you buy 1,000 residential ovens, 1,000 standard mixing bowls, 1,000 bags of flour. And you hire 1,000 humans to follow your recipe, each making their own cake in the various kitchens you’ve built.

Imagine that you are a cook, and you just made a cake in your kitchen. You’ve made a delicious cake, and you’d like to start a business making 1,000 of them a day. So you replicate your kitchen 1,000 times over—you buy 1,000 residential ovens, 1,000 standard mixing bowls, 1,000 bags of flour. And you hire 1,000 humans to follow your recipe, each making their own cake in the various kitchens you’ve built. With their bladed paws, wielded by a rippling mass of pure muscle, sharp eyes, agile reflexes, and crushing fanged jaws, lions are certainly not a predator most animals have any interest in messing with. Especially seeing as they also have the smarts to hunt in packs.

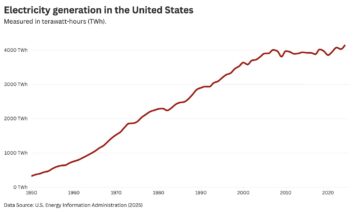

With their bladed paws, wielded by a rippling mass of pure muscle, sharp eyes, agile reflexes, and crushing fanged jaws, lions are certainly not a predator most animals have any interest in messing with. Especially seeing as they also have the smarts to hunt in packs. I often hear about “skyrocketing” demand for electricity in countries like the United States (here’s

I often hear about “skyrocketing” demand for electricity in countries like the United States (here’s

First came the

First came the  A

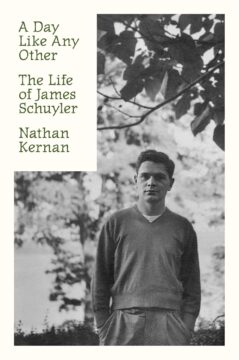

A A MAN LOOKS OVER A FENCE, SPYING. He notes the arrival of a Buick hardtop convertible. Parked now, the driver rolls the top down, using a new automatic mechanism, exposing the interior leather to the elements right at the wrong moment. The camera at first shows a magnificent three, who spill out as from a clown car: Jane Freilicher, Frank O’Hara, and John Ashbery. Then it lands on Jimmy Schuyler in the back, who, doubling as a porter, carries the luggage.

A MAN LOOKS OVER A FENCE, SPYING. He notes the arrival of a Buick hardtop convertible. Parked now, the driver rolls the top down, using a new automatic mechanism, exposing the interior leather to the elements right at the wrong moment. The camera at first shows a magnificent three, who spill out as from a clown car: Jane Freilicher, Frank O’Hara, and John Ashbery. Then it lands on Jimmy Schuyler in the back, who, doubling as a porter, carries the luggage.