Michael Gross in The New York Times:

In talks leading up to the cease-fire deal between Hamas and Israel, President Trump said he told Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, “You’re going to be remembered for this” — ending the war in Gaza — “far more than if you kept this thing going, going, going, kill, kill, kill.” Kill, kill, kill: With those words, Mr. Trump evoked the large-scale loss of life in two years of fighting. Not since the smiting days of the Old Testament have Jews killed as many people as we have killed in Gaza. The number is staggering and may reach 100,000 civilians and combatants when the rubble is cleared. This is not an accusation. It’s just the plain truth.

In talks leading up to the cease-fire deal between Hamas and Israel, President Trump said he told Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, “You’re going to be remembered for this” — ending the war in Gaza — “far more than if you kept this thing going, going, going, kill, kill, kill.” Kill, kill, kill: With those words, Mr. Trump evoked the large-scale loss of life in two years of fighting. Not since the smiting days of the Old Testament have Jews killed as many people as we have killed in Gaza. The number is staggering and may reach 100,000 civilians and combatants when the rubble is cleared. This is not an accusation. It’s just the plain truth.

No matter how we explain, justify or name it, this fact remains, and it is one that Jews — whether they opposed or supported Israel’s conduct in the war — especially in Israel but also abroad, must reckon with if the Jewish community is ever to extricate itself from the trauma of this war, which began with the Oct. 7, 2023, attack by Hamas that left some 1,200 people in Israel dead. As a nation proud of its moral tradition, how do we do this?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

When it comes to fat loss, most of us need all the help we can get. With the modern American lifestyle being largely sedentary and characterized by easy access to highly palatable, energy-dense foods, it can be very difficult to maintain the calorie deficit necessary to lose fat and keep it off. Whether or not a calorie deficit is achieved is determined by the difference between total energy in and total energy out. Assessing the “energy in” side of the equation is straightforward—add up the energy content of all food consumed. However, the “energy out” side is more complicated and much more difficult to accurately measure, as it varies by body composition, activity level, age, sex, and various other factors.

When it comes to fat loss, most of us need all the help we can get. With the modern American lifestyle being largely sedentary and characterized by easy access to highly palatable, energy-dense foods, it can be very difficult to maintain the calorie deficit necessary to lose fat and keep it off. Whether or not a calorie deficit is achieved is determined by the difference between total energy in and total energy out. Assessing the “energy in” side of the equation is straightforward—add up the energy content of all food consumed. However, the “energy out” side is more complicated and much more difficult to accurately measure, as it varies by body composition, activity level, age, sex, and various other factors. Next to an abiding interest in biology, I also have a penchant for the gothic, and a version of the collected works of Edgar Allan Poe naturally can be found in my library. But beyond the author of The Raven, who was Poe? One man who can tell me is Richard Kopley, a Distinguished Professor of English, Emeritus, at the Penn State DuBois campus of Pennsylvania State University. When this biography was published back in March, I made a mental note to revisit it for Halloween. Though my background is in biology, Kopley fortunately wants to provide for a broad readership, including “the general reader, the aficionado, and the scholar”, the goal being to “get as close to Poe as I can for as many readers as I can” (p. 4). Thus, for the last 21 days, I have immersed myself in this detailed and deeply researched biography to read of a life that was both captivating and tragic.

Next to an abiding interest in biology, I also have a penchant for the gothic, and a version of the collected works of Edgar Allan Poe naturally can be found in my library. But beyond the author of The Raven, who was Poe? One man who can tell me is Richard Kopley, a Distinguished Professor of English, Emeritus, at the Penn State DuBois campus of Pennsylvania State University. When this biography was published back in March, I made a mental note to revisit it for Halloween. Though my background is in biology, Kopley fortunately wants to provide for a broad readership, including “the general reader, the aficionado, and the scholar”, the goal being to “get as close to Poe as I can for as many readers as I can” (p. 4). Thus, for the last 21 days, I have immersed myself in this detailed and deeply researched biography to read of a life that was both captivating and tragic. Have you ever asked an AI model what’s on its mind? Or to explain how it came up with its responses? Models will sometimes answer questions like these, but it’s hard to know what to make of their answers. Can AI systems really introspect—that is, can they consider their own thoughts? Or do they just make up plausible-sounding answers when they’re asked to do so?

Have you ever asked an AI model what’s on its mind? Or to explain how it came up with its responses? Models will sometimes answer questions like these, but it’s hard to know what to make of their answers. Can AI systems really introspect—that is, can they consider their own thoughts? Or do they just make up plausible-sounding answers when they’re asked to do so? As Benjamin wrote in 1928, in his sprawling and unfinished magnum opus

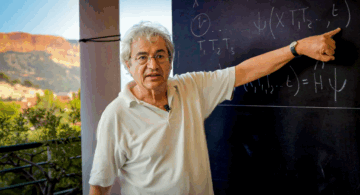

As Benjamin wrote in 1928, in his sprawling and unfinished magnum opus  Sitting outside a Catholic church on the French Riviera, Carlo Rovelli jutted his head forward and backward, imitating a pigeon trotting by. Pigeons bob their heads, he told me, not only to stabilize their vision but also to

Sitting outside a Catholic church on the French Riviera, Carlo Rovelli jutted his head forward and backward, imitating a pigeon trotting by. Pigeons bob their heads, he told me, not only to stabilize their vision but also to  G

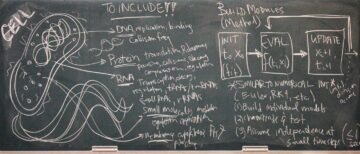

G A human cell swarms with trillions of molecules, including some 42 million proteins and a plethora of carbohydrates, lipids, and nucleic acids. Crowded with organelles and other structures, the cell boasts an intricate organization that makes baroque architecture seem plain. Its cytoplasm is a frenzied chemical lab, with molecules continuously reacting, rearranging, and reshaping. In the nucleus, thousands of genes are constantly switching on and off to turn the seeming chaos into concerted actions that help the cell survive and reproduce.

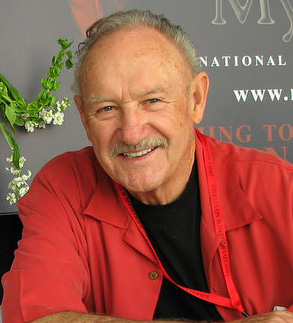

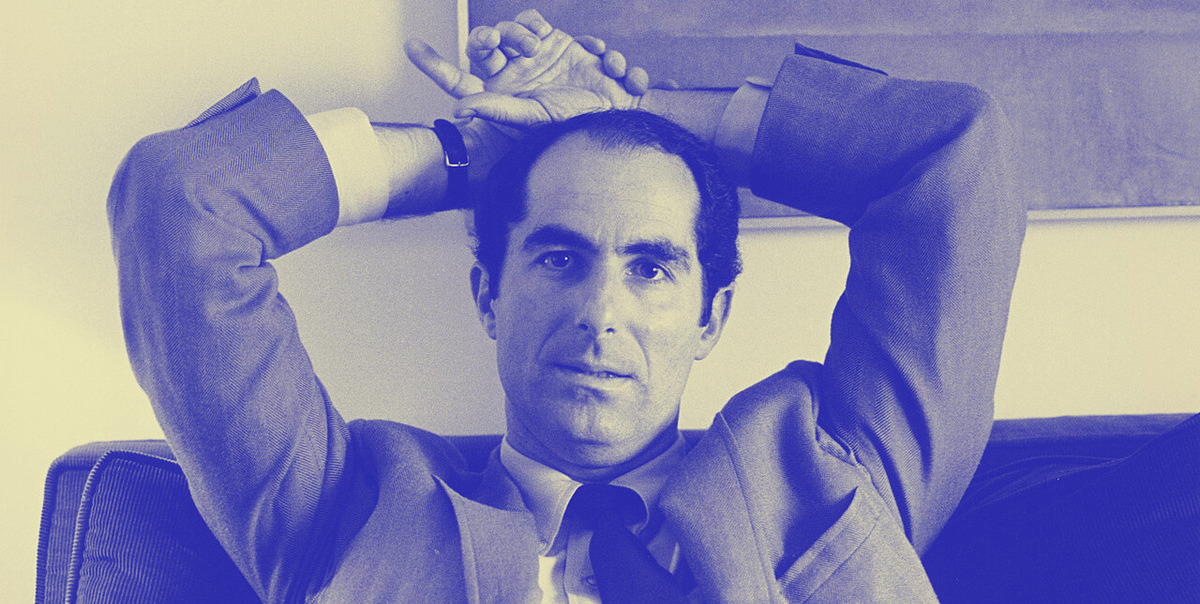

A human cell swarms with trillions of molecules, including some 42 million proteins and a plethora of carbohydrates, lipids, and nucleic acids. Crowded with organelles and other structures, the cell boasts an intricate organization that makes baroque architecture seem plain. Its cytoplasm is a frenzied chemical lab, with molecules continuously reacting, rearranging, and reshaping. In the nucleus, thousands of genes are constantly switching on and off to turn the seeming chaos into concerted actions that help the cell survive and reproduce. Already in 1967, the same year When She Was Good came out, the first samples of Portnoy’s Complaint were issued in wide-circulation magazines like Esquire and Sport, as well as the highbrow Partisan Review. Indeed, it was there, in that mainstay of the New York intelligentsia, that Roth signaled his departure from the magazine’s austere norms with the chapter entitled “Whacking Off.” Solotaroff’s new paperback journal New American Review ran two excerpted chapters of the novel, the first almost two years before the book’s appearance, the second numbering no fewer than twenty-eight thousand words.

Already in 1967, the same year When She Was Good came out, the first samples of Portnoy’s Complaint were issued in wide-circulation magazines like Esquire and Sport, as well as the highbrow Partisan Review. Indeed, it was there, in that mainstay of the New York intelligentsia, that Roth signaled his departure from the magazine’s austere norms with the chapter entitled “Whacking Off.” Solotaroff’s new paperback journal New American Review ran two excerpted chapters of the novel, the first almost two years before the book’s appearance, the second numbering no fewer than twenty-eight thousand words. The potential for AI to improve weather forecasting and climate modelling (which also takes a long time and uses a lot of energy)

The potential for AI to improve weather forecasting and climate modelling (which also takes a long time and uses a lot of energy)  As someone who has spent decades studying the evolution of nuclear energy, I’ve seen its emergence as a promising transformative technology, its stagnation as a consequence of dramatic accidents and its current re-emergence as a potential solution to the challenges of global warming.

As someone who has spent decades studying the evolution of nuclear energy, I’ve seen its emergence as a promising transformative technology, its stagnation as a consequence of dramatic accidents and its current re-emergence as a potential solution to the challenges of global warming. The central insight that these disparate thinkers took from Kant is that the world isn’t simply a thing, or a collection of things, given to us to perceive. Rather, our minds help create the reality we experience. In particular, Kant argued that time, space, and causality, which we ordinarily take for granted as the most basic aspects of the world, are better understood as forms imposed on the world by the human mind.

The central insight that these disparate thinkers took from Kant is that the world isn’t simply a thing, or a collection of things, given to us to perceive. Rather, our minds help create the reality we experience. In particular, Kant argued that time, space, and causality, which we ordinarily take for granted as the most basic aspects of the world, are better understood as forms imposed on the world by the human mind.