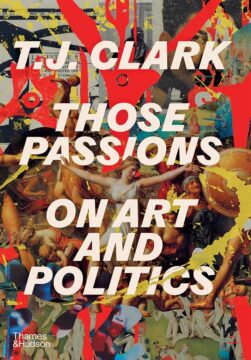

Barry Schwabsky at The Nation:

What made Clark’s appearance in the guise of an art critic an event was not just his already existing eminence as an art historian. Nor was it the fact that Clark is one of the rare art historians who has forged a style for his writing, by which I mean that he is always himself, and always recognizably himself, in his prose. Rather, it was that he was contravening the conventional division of labor within art writing: Old art is the subject of history, new art is the subject of criticism. What was thrilling about Clark’s new enterprise was that he was writing about artists such as Bosch and Velázquez not as a historian but as a critic—and yet was doing so with a historian’s erudition and authority rather than with the more approachable fluency with which a belletristic critic such as Jed Perl or Peter Schjeldahl might do so. He was, in a sense, disproving (or at least providing an exception to) Marcel Duchamp’s cynical remark that “after a work has lived almost the life of a man…comes a period when that work of art, if it is still looked at by onlookers, is put in a museum. A new generation decides that it is all right. And those two ways of judging a work of art”—before and after it is consecrated by the museum—“certainly don’t have anything in common.” Clark, by contrast, was treating the art of the past as what it is or should be, something alive and challenging in the present, and not just as what it also is, an artifact.

What made Clark’s appearance in the guise of an art critic an event was not just his already existing eminence as an art historian. Nor was it the fact that Clark is one of the rare art historians who has forged a style for his writing, by which I mean that he is always himself, and always recognizably himself, in his prose. Rather, it was that he was contravening the conventional division of labor within art writing: Old art is the subject of history, new art is the subject of criticism. What was thrilling about Clark’s new enterprise was that he was writing about artists such as Bosch and Velázquez not as a historian but as a critic—and yet was doing so with a historian’s erudition and authority rather than with the more approachable fluency with which a belletristic critic such as Jed Perl or Peter Schjeldahl might do so. He was, in a sense, disproving (or at least providing an exception to) Marcel Duchamp’s cynical remark that “after a work has lived almost the life of a man…comes a period when that work of art, if it is still looked at by onlookers, is put in a museum. A new generation decides that it is all right. And those two ways of judging a work of art”—before and after it is consecrated by the museum—“certainly don’t have anything in common.” Clark, by contrast, was treating the art of the past as what it is or should be, something alive and challenging in the present, and not just as what it also is, an artifact.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.