Jennifer Wilson at the NYT:

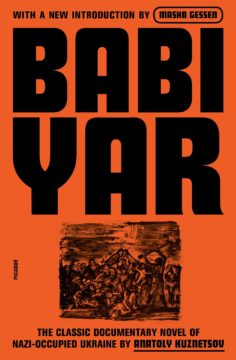

On Sept. 29 and 30, 1941, in a ravine just outside Kyiv called Babyn Yar (“Babi Yar” in Russian), Nazis executed nearly 34,000 Jews over the course of 36 hours. It was the deadliest mass execution in what came to be known as the “Holocaust by Bullets.” We were never supposed to know it happened. In 1943, as the Nazis fled Kyiv, they ordered the bodies in Babyn Yar to be dug up and burned, to erase all memory of what they’d done.

On Sept. 29 and 30, 1941, in a ravine just outside Kyiv called Babyn Yar (“Babi Yar” in Russian), Nazis executed nearly 34,000 Jews over the course of 36 hours. It was the deadliest mass execution in what came to be known as the “Holocaust by Bullets.” We were never supposed to know it happened. In 1943, as the Nazis fled Kyiv, they ordered the bodies in Babyn Yar to be dug up and burned, to erase all memory of what they’d done.

The Nazis planned to kill the workers they tasked with destroying the bodies. “But they didn’t succeed,” one declared proudly. The Ukrainian filmmaker Sergei Loznitsa included newsreel footage in his documentary “Babi Yar. Context” (2021) of one of the men giving an interview. He and 12 others (out of 300) escaped “and can now testify,” he tells the camera, “to the whole world and our motherland to the acts of barbarity committed by those fascist dogs in our beloved Kyiv.”

more here.

W

W

The specter of being trapped in a world of illusions has haunted humankind much longer than the specter of A.I. Soon we will finally come face to face with Descartes’s demon, with Plato’s cave, with the Buddhist Maya. A curtain of illusions could descend over the whole of humanity, and we might never again be able to tear that curtain away — or even realize it is there.

The specter of being trapped in a world of illusions has haunted humankind much longer than the specter of A.I. Soon we will finally come face to face with Descartes’s demon, with Plato’s cave, with the Buddhist Maya. A curtain of illusions could descend over the whole of humanity, and we might never again be able to tear that curtain away — or even realize it is there. Between 1910 and 1940, thousands of Chinese immigrants were detained—sometimes for months—in facilities on Angel Island, off the coast of San Francisco.

Between 1910 and 1940, thousands of Chinese immigrants were detained—sometimes for months—in facilities on Angel Island, off the coast of San Francisco. A record outbreak of

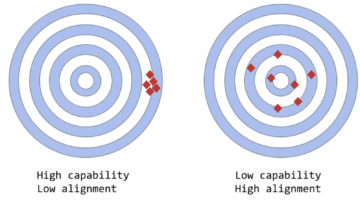

A record outbreak of  The very deepest worries center around the question of AGI, Artificial General Intelligence, and the question of the Singularity. AGI is a form of artificial intelligence so advanced that it could understand the world at least as well as a human being in every way that a human being can. It is not too far a step from such a possibility to the idea of AGIs that can produce AGIs and improve both upon themselves and further generations of AGI. This leads to the Singularity, a point at which this production of super-intelligence goes so far beyond that which humans are capable of imagining that, in essence, all bets are off. We can’t know what such beings would be like, nor what they would do. Which sets up the alignment problem. How do you possibly align the interests of super intelligent AGIs with those of puny humans? And as many have suggested, wouldn’t a super intelligent self-interested AGI be rather incentivized to get rid of us, since we are its most direct threat and/or inconvenience? And even if super AGIs did not want to exterminate humans, what is to ensure that they would care much what happens to us either way?

The very deepest worries center around the question of AGI, Artificial General Intelligence, and the question of the Singularity. AGI is a form of artificial intelligence so advanced that it could understand the world at least as well as a human being in every way that a human being can. It is not too far a step from such a possibility to the idea of AGIs that can produce AGIs and improve both upon themselves and further generations of AGI. This leads to the Singularity, a point at which this production of super-intelligence goes so far beyond that which humans are capable of imagining that, in essence, all bets are off. We can’t know what such beings would be like, nor what they would do. Which sets up the alignment problem. How do you possibly align the interests of super intelligent AGIs with those of puny humans? And as many have suggested, wouldn’t a super intelligent self-interested AGI be rather incentivized to get rid of us, since we are its most direct threat and/or inconvenience? And even if super AGIs did not want to exterminate humans, what is to ensure that they would care much what happens to us either way? There are certain sweet-smelling, sugarcoated lies current in the world which all politic men have apparently tacitly conspired together to support and perpetuate. One of these is that there is such a thing in the world as independence: independence of thought, independence of opinion, independence of action.

There are certain sweet-smelling, sugarcoated lies current in the world which all politic men have apparently tacitly conspired together to support and perpetuate. One of these is that there is such a thing in the world as independence: independence of thought, independence of opinion, independence of action. Scientists who study happiness know that being kind to others

Scientists who study happiness know that being kind to others  It’s all wrong. The wrongness is pervasive; you could not, if asked, identify the it or the its that went wrong. Wrongness leaches into everything, like the microplastics you read about, which may or may not be reducing sperm count in men, which may or may not be good, in the long run—it’s something to do with the environment. Someone wanted you to feel one way or the other about it, but you can’t remember who or why or whether you agreed with him. Everyone speaks so authoritatively, whether it’s on the evening news or a podcast, in an Internet video or a book, or even in one of those Twitter threads that begins (irksomely, you once felt, but now you don’t notice) with the little picture of a spool. Authority makes them all sound the same; it crosses all their faces and leaves many of the same furrows. Only afterward, trying to add it all up, do you half-remember that none of them agreed with each other. But the wrongness you can be sure of. It is like God, undergirding all things.

It’s all wrong. The wrongness is pervasive; you could not, if asked, identify the it or the its that went wrong. Wrongness leaches into everything, like the microplastics you read about, which may or may not be reducing sperm count in men, which may or may not be good, in the long run—it’s something to do with the environment. Someone wanted you to feel one way or the other about it, but you can’t remember who or why or whether you agreed with him. Everyone speaks so authoritatively, whether it’s on the evening news or a podcast, in an Internet video or a book, or even in one of those Twitter threads that begins (irksomely, you once felt, but now you don’t notice) with the little picture of a spool. Authority makes them all sound the same; it crosses all their faces and leaves many of the same furrows. Only afterward, trying to add it all up, do you half-remember that none of them agreed with each other. But the wrongness you can be sure of. It is like God, undergirding all things. The creators have used a combination of both Supervised Learning and Reinforcement Learning to fine-tune ChatGPT, but it is the Reinforcement Learning component specifically that makes ChatGPT unique. The creators use a particular technique called Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), which uses human feedback in the training loop to minimize harmful, untruthful, and/or biased outputs.

The creators have used a combination of both Supervised Learning and Reinforcement Learning to fine-tune ChatGPT, but it is the Reinforcement Learning component specifically that makes ChatGPT unique. The creators use a particular technique called Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), which uses human feedback in the training loop to minimize harmful, untruthful, and/or biased outputs. For years, philanthropists have poured money into progressive climate groups, while

For years, philanthropists have poured money into progressive climate groups, while

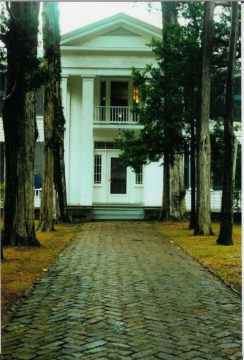

After I’d wandered the grounds, I spent the weekend in Oxford, a heady experience for a Northern fetishist of things Southern. I ate catfish and grits, drank whiskey in a bar on the outskirts of town where old men in hats played guitars. I visited Faulkner’s grave and his birthplace, drove around the Mississippi hill country, and ate okra with congenial strangers. I tried to understand why I felt drawn to this part of the world. To that end, I drank whiskey in a second bar, this one downtown, overlooking the statue of the Confederate soldier who gazed “with empty eyes,” in Faulkner’s phrase, at the square. I decided the reason was this. I grew up in Amherst, a mile down the road from Dickinson’s house, and Massachusetts is the Mississippi of the North, Mississippi the Massachusetts of the South. They’re on opposite sides of the American political spectrum, but they’re both places where the present is dwarfed and chastened by the past. In Massachusetts, a given location is known as the spot where the minutemen faced the redcoats on the green, or where Jonathan Edwards delivered his sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” or where the Mayflower landed, or where the whalers set sail, or where the tea was dumped in the harbor. In Mississippi, it’s the same: here’s where Grant’s army bivouacked; here’s where the formerly enslaved Union soldiers drove the Texans from the field; here’s where Elvis grew up; here’s where Emmett Till was murdered; here’s where the earliest blues music was performed. I’ve heard both Massachusetts and Mississippi maligned as boring, and I’ve tried to explain to the maligners: You need to stop living so much in the present.

After I’d wandered the grounds, I spent the weekend in Oxford, a heady experience for a Northern fetishist of things Southern. I ate catfish and grits, drank whiskey in a bar on the outskirts of town where old men in hats played guitars. I visited Faulkner’s grave and his birthplace, drove around the Mississippi hill country, and ate okra with congenial strangers. I tried to understand why I felt drawn to this part of the world. To that end, I drank whiskey in a second bar, this one downtown, overlooking the statue of the Confederate soldier who gazed “with empty eyes,” in Faulkner’s phrase, at the square. I decided the reason was this. I grew up in Amherst, a mile down the road from Dickinson’s house, and Massachusetts is the Mississippi of the North, Mississippi the Massachusetts of the South. They’re on opposite sides of the American political spectrum, but they’re both places where the present is dwarfed and chastened by the past. In Massachusetts, a given location is known as the spot where the minutemen faced the redcoats on the green, or where Jonathan Edwards delivered his sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” or where the Mayflower landed, or where the whalers set sail, or where the tea was dumped in the harbor. In Mississippi, it’s the same: here’s where Grant’s army bivouacked; here’s where the formerly enslaved Union soldiers drove the Texans from the field; here’s where Elvis grew up; here’s where Emmett Till was murdered; here’s where the earliest blues music was performed. I’ve heard both Massachusetts and Mississippi maligned as boring, and I’ve tried to explain to the maligners: You need to stop living so much in the present.