“You can’t write poems about the trees when the woods are full of policemen.”

…………………………………………………………………………………… —Bertolt Brecht

Broken Ghazal for Walter Scott

A video looping like a dirge on repeat, my soul—a psalm of bullets in my back.

I see you running, then drop, heavy hunted like prey with eight shots in the back.

Again, in my Facebook feed another black man dead, another fist in my throat.

You: prostrate on the green grass, handcuffed with your hands tied to your back.

Praises for the video, to the witness & his recording thumb, praises to YouTube

for taking the blindfold off Lady Justice, dipping her scales down with old weight

of strange fruit, to American eyeballs blinking & chewing the 24-hour news cycle:

another black body, another white cop. But let us go back to the broken tail light,

let’s find a man behind on his child support, let’s become his children, let’s call him

Papa. Let us chant Papa don’t run! Stay, stay back! Stay here with us. But Tiana—

you have got to stop watching this video. Walter is gone & he is not your daddy,

another story will come to your feed, stay back. But whisper—stay, once more,

with the denied breath of his absent CPR, praise his mother strumming Santana

with tiny hallelujahs up & down the harp of his back. Praise his mother hugging

the man who made her son a viral hit, a rerun to watch him die ad infintum, again

we go back, click replay at any moment. A video looping like a dirge on repeat—

by Tianna Clark

from I Can’t Talk About the Trees Without the Blood

University of Pittsburgh Press, 2018

Czech writer

Czech writer  There are a handful of topics that I almost force myself to not think about because the thoughts lead to a dead end. At the top of that list is climate change. It’s one of those problems that starts to overwhelm me when I consider the scale and the implications and all the barriers to tackling it.

There are a handful of topics that I almost force myself to not think about because the thoughts lead to a dead end. At the top of that list is climate change. It’s one of those problems that starts to overwhelm me when I consider the scale and the implications and all the barriers to tackling it. The Maharaja of Whereverstan sends his daughter to Harvard so that she appears meritorious. In exchange, Harvard gets the credibility boost of being the place the Maharaja of Whereverstan sent his daughter. And Harvard’s other students get the advantage of networking with the Princess Of Whereverstan. Twenty years later, when one of them is an oil executive and Whereverstan is handing out oil contracts, she puts in a word with her old college buddy the Princess and gets the deal. It’s obvious what the oil executive has gotten out of this, but what does the Princess get? I think she gets the right to say she went to Harvard, an honor which is known to go mostly to the meritorious.

The Maharaja of Whereverstan sends his daughter to Harvard so that she appears meritorious. In exchange, Harvard gets the credibility boost of being the place the Maharaja of Whereverstan sent his daughter. And Harvard’s other students get the advantage of networking with the Princess Of Whereverstan. Twenty years later, when one of them is an oil executive and Whereverstan is handing out oil contracts, she puts in a word with her old college buddy the Princess and gets the deal. It’s obvious what the oil executive has gotten out of this, but what does the Princess get? I think she gets the right to say she went to Harvard, an honor which is known to go mostly to the meritorious. In hindsight it seems inevitable: a single overarching internet is impossible. The worldviews of people are too fundamentally incompatible at their roots. Or to simplify and put it more bluntly: at least in the United States, there is no way to fit both major political parties onto the same platform and allow them to wield equal power over a perfectly centered Overton window. Blame whichever side you want, red or blue. I’m sure it’s the other side that’s more extreme (and hey, maybe you’re right). But if Twitter was supposed to be the “global town square,” I think Zuckerberg’s so-far successful introduction of its competitor, Threads, which rapidly feels like the other global town square, presages one of the last gasps of the united internet, and the end of an important, if uncomfortable, era. Yes, it was an era of half a billion people crammed into a single echoing room, all our faces smooshed against one another, and all you could taste was the spittle and there was ringing in your ears as the crowd surged. But it was also the time when you could say something and, just occasionally, the entire world would hear it.

In hindsight it seems inevitable: a single overarching internet is impossible. The worldviews of people are too fundamentally incompatible at their roots. Or to simplify and put it more bluntly: at least in the United States, there is no way to fit both major political parties onto the same platform and allow them to wield equal power over a perfectly centered Overton window. Blame whichever side you want, red or blue. I’m sure it’s the other side that’s more extreme (and hey, maybe you’re right). But if Twitter was supposed to be the “global town square,” I think Zuckerberg’s so-far successful introduction of its competitor, Threads, which rapidly feels like the other global town square, presages one of the last gasps of the united internet, and the end of an important, if uncomfortable, era. Yes, it was an era of half a billion people crammed into a single echoing room, all our faces smooshed against one another, and all you could taste was the spittle and there was ringing in your ears as the crowd surged. But it was also the time when you could say something and, just occasionally, the entire world would hear it. CHOMSKY: Von Humboldt was, first of all, a great linguist who recognized some fundamental principles of language which were rare at the time and are only beginning to be understood. But in the social and political domain, he was not only the founder of the modern research university, but also one of the founders of classical liberalism.

CHOMSKY: Von Humboldt was, first of all, a great linguist who recognized some fundamental principles of language which were rare at the time and are only beginning to be understood. But in the social and political domain, he was not only the founder of the modern research university, but also one of the founders of classical liberalism.

McCarthy’s writing is poetic. By that I mean that many of McCarthy’s sentences do not appear to exist to serve some purpose outside themselves: their language, the texture of the sounds, the relations (often ironic, in his case) between the words and their meanings—all this is the province of poetry.

McCarthy’s writing is poetic. By that I mean that many of McCarthy’s sentences do not appear to exist to serve some purpose outside themselves: their language, the texture of the sounds, the relations (often ironic, in his case) between the words and their meanings—all this is the province of poetry. The hush at the end of the musical performance. The pause in a dramatic speech. The muted moment when you turn off the car. What is it that we hear when we hear nothing at all? Are we detecting silence? Or are we just hearing nothing and interpreting that absence as silence?

The hush at the end of the musical performance. The pause in a dramatic speech. The muted moment when you turn off the car. What is it that we hear when we hear nothing at all? Are we detecting silence? Or are we just hearing nothing and interpreting that absence as silence? In 1988, the great Lutheran scholar Robert Jenson published a book called America’s Theologian, conferring that honor on the formidable eighteenth-century Calvinist divine Jonathan Edwards. Jenson did not mean that Edwards is the greatest American theologian, though he probably is, but rather “that Edwards’s theology meets precisely the problems and opportunities of specifically American Christianity and of the nation molded thereby, and that it does so with the profundity and inventive élan that belong only to the very greatest thinkers.”

In 1988, the great Lutheran scholar Robert Jenson published a book called America’s Theologian, conferring that honor on the formidable eighteenth-century Calvinist divine Jonathan Edwards. Jenson did not mean that Edwards is the greatest American theologian, though he probably is, but rather “that Edwards’s theology meets precisely the problems and opportunities of specifically American Christianity and of the nation molded thereby, and that it does so with the profundity and inventive élan that belong only to the very greatest thinkers.” In 2019, Christian Szegedy, a computer scientist formerly at Google and now at a start-up in the Bay Area, predicted that a computer system would match or exceed the problem-solving ability of the best human mathematicians within a decade. Last year he revised the target date to 2026.

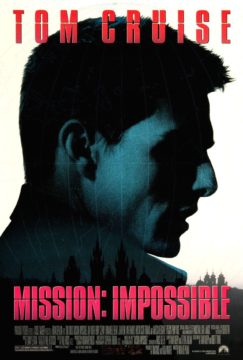

In 2019, Christian Szegedy, a computer scientist formerly at Google and now at a start-up in the Bay Area, predicted that a computer system would match or exceed the problem-solving ability of the best human mathematicians within a decade. Last year he revised the target date to 2026. Over time, Ethan Hunt and his geopolitical exploits have remained a rare cultural constant through a time of real-world geopolitical upheaval. Mission: Impossible’s six installments have been with the United States across three recessions, five presidents, at least two wars, and a global pandemic. That’s the kind of longevity that transforms a franchise from a series of ephemeral blockbusters with loosely connected plots into a quasi-reliable witness to history who has stuck around long enough to recall a few important things, even if its memories are a little hazy, and for some reason all involve Ving Rhames wearing a fedora.

Over time, Ethan Hunt and his geopolitical exploits have remained a rare cultural constant through a time of real-world geopolitical upheaval. Mission: Impossible’s six installments have been with the United States across three recessions, five presidents, at least two wars, and a global pandemic. That’s the kind of longevity that transforms a franchise from a series of ephemeral blockbusters with loosely connected plots into a quasi-reliable witness to history who has stuck around long enough to recall a few important things, even if its memories are a little hazy, and for some reason all involve Ving Rhames wearing a fedora. First, the physical effort of driving a race car is much greater than that of driving your family car.

First, the physical effort of driving a race car is much greater than that of driving your family car. Eyes follow you from behind a slit in a translucent sheet. A tear, loosely sewn, cuts across an image. A nose emerges, and elsewhere faces float in repose, softened and semi-hidden. Overlays, cuts, and stitches in the smoky surface create a game of hide and seek. Perhaps we’ve caught someone mid-dream, but who? The person in the portrait or the artist herself?

Eyes follow you from behind a slit in a translucent sheet. A tear, loosely sewn, cuts across an image. A nose emerges, and elsewhere faces float in repose, softened and semi-hidden. Overlays, cuts, and stitches in the smoky surface create a game of hide and seek. Perhaps we’ve caught someone mid-dream, but who? The person in the portrait or the artist herself? There I was, sitting in a New Jersey Burger King, while the restaurant manager I was on a date shouted the lyrics to Rule, Britannia! at the top of his lungs. I had just started eating my Whopper meal when he started belting it out, his arms firmly placed on my shoulders. “She’s British! She’s British,” he shouted at the various people who were just getting on with their day, but were clearly wondering what on earth was going on. Well, this is going to be fantastic, I thought. I was in my mid-40s at the time, and had no real plan other than which states I would be visiting, placing newspaper adverts in New York, New Jersey, Los Angeles, Miami, and Philadelphia claiming to be a single woman looking for love.

There I was, sitting in a New Jersey Burger King, while the restaurant manager I was on a date shouted the lyrics to Rule, Britannia! at the top of his lungs. I had just started eating my Whopper meal when he started belting it out, his arms firmly placed on my shoulders. “She’s British! She’s British,” he shouted at the various people who were just getting on with their day, but were clearly wondering what on earth was going on. Well, this is going to be fantastic, I thought. I was in my mid-40s at the time, and had no real plan other than which states I would be visiting, placing newspaper adverts in New York, New Jersey, Los Angeles, Miami, and Philadelphia claiming to be a single woman looking for love.