Brendan O’Neill in Spiked:

‘Decolonise the curriculum’ is a movement that wants university courses to focus less on dead white European males and more on writers of colour. Its argument is that black students need texts that speak directly to them. They need books by authors who look like them. They need books about experiences and ideas they can more readily relate to than they can the stuff written about in ‘high white culture’. Black students must be able to recognise themselves in what they study, we’re told, or else they’ll feel cheated and demeaned.

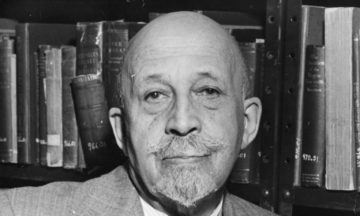

I was surprised to find that one of the leading decolonise movements, at the University of Edinburgh, was arguing for WEB Du Bois’ 1903 book, The Souls of Black Folk, to be included on the English curriculum. The activists said it was unreasonable to expect black students to engage with so many white authors. They also need to engage with people like Du Bois, in whose work they might ‘recognise themselves’. I was surprised, not because I think The Souls of Black Folk shouldn’t be on more university courses – absolutely it should. No, it’s because The Souls of Black Folk runs so fantastically counter to the entire ideology of ‘decolonise’. It made me wonder if these activists have even read it. Du Bois’ book contains some of the finest arguments you will ever read against the idea that high culture is a white thing that others cannot connect with.

More here.

Remo Verdickt and Emiel Roothooft in LA Review of Books:

Remo Verdickt and Emiel Roothooft in LA Review of Books: On 22 February1946, George Kennan, an American diplomat stationed in Moscow, dictated a 5,000-word cable to Washington. In this famous telegram, Kennan warned that the Soviet Union’s commitment to communism meant that it was inherently expansionist, and urged the US government to resist any attempts by the Soviets to increase their influence. This strategy quickly became known as “containment” – and defined American foreign policy for the next 40 years.

On 22 February1946, George Kennan, an American diplomat stationed in Moscow, dictated a 5,000-word cable to Washington. In this famous telegram, Kennan warned that the Soviet Union’s commitment to communism meant that it was inherently expansionist, and urged the US government to resist any attempts by the Soviets to increase their influence. This strategy quickly became known as “containment” – and defined American foreign policy for the next 40 years. For Julian Huxley, science was spiritual. The biologist, brother of the novelist Aldous Huxley and grandson of “Darwin’s Bulldog”

For Julian Huxley, science was spiritual. The biologist, brother of the novelist Aldous Huxley and grandson of “Darwin’s Bulldog”  Writing is a solitary practice;

Writing is a solitary practice; Quantum computers have long promised to solve certain problems faster than any ordinary, or classical, computer can. In fact, Google delivered on this promise in 2019, when it

Quantum computers have long promised to solve certain problems faster than any ordinary, or classical, computer can. In fact, Google delivered on this promise in 2019, when it  In November, the United Kingdom will host a high-profile international summit on the governance of artificial intelligence. With the agenda and list of invitees still being finalized, the biggest decision facing UK officials is whether to invite China or host a more exclusive gathering for the G7 and other countries that want to safeguard liberal democracy as the foundation for a digital society.

In November, the United Kingdom will host a high-profile international summit on the governance of artificial intelligence. With the agenda and list of invitees still being finalized, the biggest decision facing UK officials is whether to invite China or host a more exclusive gathering for the G7 and other countries that want to safeguard liberal democracy as the foundation for a digital society. On a 95-degree evening in Austin last fall, I ran into a curator from the University of Texas’ Blanton Museum of Art at a gallery reception across town. We briefly chatted about the Blanton’s then recently opened “Ellsworth Kelly: Postcards” exhibition, which had been organized by the Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College. I mentioned I was covering the show for Salmagundi and that I was very much looking forward to seeing the presentation—a departure from the artist’s much larger monochromatic works—up close and personal, and possibly with a pair of reading glasses.

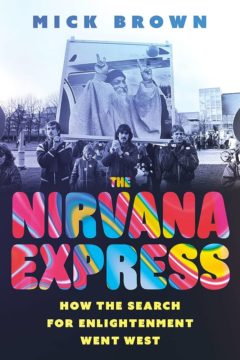

On a 95-degree evening in Austin last fall, I ran into a curator from the University of Texas’ Blanton Museum of Art at a gallery reception across town. We briefly chatted about the Blanton’s then recently opened “Ellsworth Kelly: Postcards” exhibition, which had been organized by the Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College. I mentioned I was covering the show for Salmagundi and that I was very much looking forward to seeing the presentation—a departure from the artist’s much larger monochromatic works—up close and personal, and possibly with a pair of reading glasses. Not so long ago, India’s greatest export to the West, people aside, was spirituality. Mick Brown’s The Nirvana Express is an engaging history of India’s spiritual influence on the West between 1893, when Swami Vivekananda was the surprise star at the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago, and 1990, when the multimillionaire cult leader and tax dodger Bhagwan Rajneesh popped his sandals. The economic reforms that began the transformation of India’s economy started a year after Rajneesh’s death. The subsequent changes make the history described in Nirvana Express feel almost ancient.

Not so long ago, India’s greatest export to the West, people aside, was spirituality. Mick Brown’s The Nirvana Express is an engaging history of India’s spiritual influence on the West between 1893, when Swami Vivekananda was the surprise star at the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago, and 1990, when the multimillionaire cult leader and tax dodger Bhagwan Rajneesh popped his sandals. The economic reforms that began the transformation of India’s economy started a year after Rajneesh’s death. The subsequent changes make the history described in Nirvana Express feel almost ancient. FRANZ KAFKA’S LAST STORYwas a fable about art and labor. “Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse Folk” is a tale told by a mouse who, with marked erudition and fair-mindedness, reflects on an extraordinary community member, the singer Josephine. At times of danger or emergency, the news will spread that she plans to sing. The community assembles, and Josephine, delicate and frail, stands before them in song, her arms spread wide, her throat stretched high. The tones emanating from that delicate throat are, according to some, not singing at all but rather ordinary piping—if anything, weaker and thinner than the sounds all mice make. It is peculiar, the narrator considers, that “here is someone making a ceremonial performance out of doing the usual thing.” But her art has a strange hold on all who listen. It turns the ordinary materials of speech into something transcendent.

FRANZ KAFKA’S LAST STORYwas a fable about art and labor. “Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse Folk” is a tale told by a mouse who, with marked erudition and fair-mindedness, reflects on an extraordinary community member, the singer Josephine. At times of danger or emergency, the news will spread that she plans to sing. The community assembles, and Josephine, delicate and frail, stands before them in song, her arms spread wide, her throat stretched high. The tones emanating from that delicate throat are, according to some, not singing at all but rather ordinary piping—if anything, weaker and thinner than the sounds all mice make. It is peculiar, the narrator considers, that “here is someone making a ceremonial performance out of doing the usual thing.” But her art has a strange hold on all who listen. It turns the ordinary materials of speech into something transcendent. Pakistan has introduced measures against modern slavery with mixed success. Climate change, however, is reinforcing the most egregious abuses due to mounting personal debt, and the economic relationship between sharecroppers and small farmers on the one hand, and landlords and local merchants on the other.

Pakistan has introduced measures against modern slavery with mixed success. Climate change, however, is reinforcing the most egregious abuses due to mounting personal debt, and the economic relationship between sharecroppers and small farmers on the one hand, and landlords and local merchants on the other.