Cedric Durand in Sidecar:

In a 1977 lecture at the Collège de France, later published in How to Live Together, Roland Barthes explored a ‘fantasy of a life, a regime, a lifestyle’ that was neither reclusive nor communal: ‘Something like solitude with regular interruptions’. Inspired by the monks of Mount Athos, Barthes proposed to call this mode of living together idiorrhythmy, from the Greek idios (one’s own) and rythmos (rhythm). ‘Fantasmatically speaking’, he says, ‘there is nothing contradictory about wanting to live alone and wanting to live together’. In idiorrhythmic communities, ‘each subject lives according to his own rhythm’ while still being ‘in contact with one another within a particular type of structure’.

Although in Barthes’ view this unregimented lifestyle would be the exact opposite of ‘the fundamental inhumanity of Fourier’s Phalanstery with its timing of each and every quarter hour’, his vision is similarly utopian. But whereas Fourier proposed a plan for an organized, enclosed community, Barthes was not so much sketching a model as seeking to define a zone between two extreme forms of living: ‘an excessively negative form: solitude, eremitism’ and ‘an excessively assimilative form: the convent or monastery’. Idiorrhythmy is thus ‘a median, utopian, Edenic, idyllic form’: a ‘utopia of a socialism of distance’. In this middle way between living alone and with others, the interplay between individuals is so light and subtle that it allows each to escape the diktat of heterorhythmy, where one must submit to power and conform to an alien rhythm imposed from outside.

More here.

David Klion in The Baffler:

David Klion in The Baffler: Gary Edward Holcomb in LA Review of Books:

Gary Edward Holcomb in LA Review of Books: A doppelgänger is a double, a person who appears so similar to another that they could easily stand in for them, maybe even take over their life. “The idea that two strangers can be indistinguishable from each other taps into the precariousness at the core of identity,” Klein writes. In Philip Roth’s novel

A doppelgänger is a double, a person who appears so similar to another that they could easily stand in for them, maybe even take over their life. “The idea that two strangers can be indistinguishable from each other taps into the precariousness at the core of identity,” Klein writes. In Philip Roth’s novel  “Built for giants, inhabited by pygmies.” That’s what the legendary Texas politician

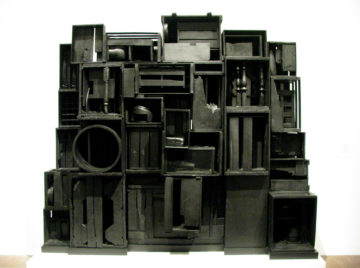

“Built for giants, inhabited by pygmies.” That’s what the legendary Texas politician  THE ICONIC LOUISE NEVELSON sculpture would appear straightforward to summarize: monochrome, modular, monumental. In general, such qualities—and to them we might add wooden, assemblage, usually black, comprising found objects—indicate an artist singularly absorbed, working through a set of formal propositions over a career, pursuing the archetypal enterprise of the modernist master. In particular, though, up close and personal, Nevelson’s sculptures are, well, defiantly weird.

THE ICONIC LOUISE NEVELSON sculpture would appear straightforward to summarize: monochrome, modular, monumental. In general, such qualities—and to them we might add wooden, assemblage, usually black, comprising found objects—indicate an artist singularly absorbed, working through a set of formal propositions over a career, pursuing the archetypal enterprise of the modernist master. In particular, though, up close and personal, Nevelson’s sculptures are, well, defiantly weird. W

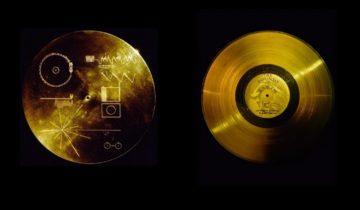

W There are alien minds among us. Not the little green men of science fiction, but the alien minds that power the facial recognition in your smartphone,

There are alien minds among us. Not the little green men of science fiction, but the alien minds that power the facial recognition in your smartphone,  T

T The ceremony takes place on the night of the full moon in February, which the Tibetans celebrate as the coldest of the year. Buddhist monks clad in light cotton shawls climb to a rocky ledge some 15,000 feet high and go to sleep, in child’s pose, foreheads pressed against cold Himalayan rocks. In the dead of the night, temperatures plummet below freezing but the monks sleep on peacefully, without shivering.

The ceremony takes place on the night of the full moon in February, which the Tibetans celebrate as the coldest of the year. Buddhist monks clad in light cotton shawls climb to a rocky ledge some 15,000 feet high and go to sleep, in child’s pose, foreheads pressed against cold Himalayan rocks. In the dead of the night, temperatures plummet below freezing but the monks sleep on peacefully, without shivering. Some

Some  I

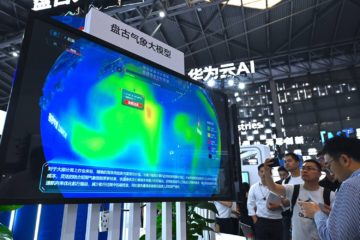

I Over the past two years, China has enacted some of the world’s earliest and most sophisticated

Over the past two years, China has enacted some of the world’s earliest and most sophisticated