David Platzker at Artforum:

Ruscha’s avant-garde proclivities surfaced in his first pagework as a member of the group Students Five, a collective of friends—Joe Good, Jerry McMillan (both high-school classmates of Ruscha’s), Patrick Blackwell, Don Moore, and later Wall Batterton. Their mailer/bulletin, Orb,9 published in seven issues between 1959 and 1960 by Chouinard’s Society of Graphic Designers, contained an amalgam of cartoons, collages, graphic experiments, texts, and exhibition announcements. Ruscha edited and laid out the issues on a single seventeen-by-twenty-two-inch sheet, printing it recto-verso in an elaborate overlapping two-color system and folding it six times down for dissemination through the mail. Commenting on the genesis of Orb’s design, Ruscha would say, “I pasted the thing up and I maybe was thinking in the back of my head, Dada, ’cause they kind of echo a lot of the things that the Dadaists were doing. Things can be upside down, they don’t have to be orderly, you don’t have to have a proper well-behaved page line.”

Ruscha’s avant-garde proclivities surfaced in his first pagework as a member of the group Students Five, a collective of friends—Joe Good, Jerry McMillan (both high-school classmates of Ruscha’s), Patrick Blackwell, Don Moore, and later Wall Batterton. Their mailer/bulletin, Orb,9 published in seven issues between 1959 and 1960 by Chouinard’s Society of Graphic Designers, contained an amalgam of cartoons, collages, graphic experiments, texts, and exhibition announcements. Ruscha edited and laid out the issues on a single seventeen-by-twenty-two-inch sheet, printing it recto-verso in an elaborate overlapping two-color system and folding it six times down for dissemination through the mail. Commenting on the genesis of Orb’s design, Ruscha would say, “I pasted the thing up and I maybe was thinking in the back of my head, Dada, ’cause they kind of echo a lot of the things that the Dadaists were doing. Things can be upside down, they don’t have to be orderly, you don’t have to have a proper well-behaved page line.”

more here.

What distinguished the relationship between Gefter and Marks—other than the fact that it had lasted an eternity in gay years—was the photography. Inspired by the breathtaking tenderness of Alfred Stieglitz’s portraits of Georgia O’Keeffe, and Emmet Gowin’s of Edith Morris, Gefter, who had recently completed a BFA in photography and painting at the Pratt Institute, set out to document his romance with Marks, who, in turn, always insisted on reciprocating the photographic act. An archive of portraits, spontaneously taken by one another in moments of affection, lust, anxiety, jealousy, and fury, is the point of departure for their dialogues with Denneny. In his 2023 book On Christopher Street: Life, Sex, and Death after Stonewall, Denneny, who died this past April, described his aspiration to “make something like a literary or intellectual version of a Joseph Cornell box, using Philip and Neil’s photographs, the live interviews, and the written self-portraits to capture something—love, passion, and its loss—that I was obsessed with.”

What distinguished the relationship between Gefter and Marks—other than the fact that it had lasted an eternity in gay years—was the photography. Inspired by the breathtaking tenderness of Alfred Stieglitz’s portraits of Georgia O’Keeffe, and Emmet Gowin’s of Edith Morris, Gefter, who had recently completed a BFA in photography and painting at the Pratt Institute, set out to document his romance with Marks, who, in turn, always insisted on reciprocating the photographic act. An archive of portraits, spontaneously taken by one another in moments of affection, lust, anxiety, jealousy, and fury, is the point of departure for their dialogues with Denneny. In his 2023 book On Christopher Street: Life, Sex, and Death after Stonewall, Denneny, who died this past April, described his aspiration to “make something like a literary or intellectual version of a Joseph Cornell box, using Philip and Neil’s photographs, the live interviews, and the written self-portraits to capture something—love, passion, and its loss—that I was obsessed with.” The cells of all living organisms are powered by the same chemical fuel:

The cells of all living organisms are powered by the same chemical fuel:  A research team headed by Prof. Jacob Hanna at the Weizmann Institute of Science has created complete models of human embryos from stem cells cultured in the lab—and managed to grow them outside the womb up to day 14.

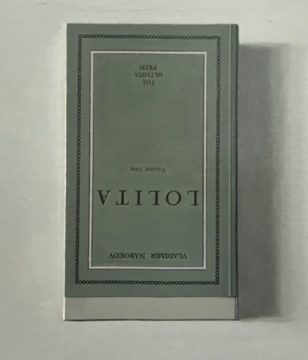

A research team headed by Prof. Jacob Hanna at the Weizmann Institute of Science has created complete models of human embryos from stem cells cultured in the lab—and managed to grow them outside the womb up to day 14.  Lolita was originally published as a limited edition in France in September 1955. The book was released by Maurice Girodias of Olympia Press, a company known for specializing in pornography, but which had also built a reputation for publishing challenging literary titles. The first print run had been 5,000 copies and the book received little attention.

Lolita was originally published as a limited edition in France in September 1955. The book was released by Maurice Girodias of Olympia Press, a company known for specializing in pornography, but which had also built a reputation for publishing challenging literary titles. The first print run had been 5,000 copies and the book received little attention. Since modernity began, people have complained about airborne dust – but the measures required to control it have come decades or centuries after, if at all. The coalmines and factories that powered Britain’s Industrial Revolution made a capitalist class very rich, while the cost was borne by their workers in their bodies, lungs and blood. The Ethics of Dust was, for me, about human presence made present – about the building rewritten as not only limestone and glass and a wood-beamed roof, or as big abstract nouns like history and tradition and power, but the material traces of millions of bodies, their labours and their livelihoods. It brings the polis, the people, right into the heart of parliament – and it brings a reckoning with the source of Britain’s historical prosperity, too.

Since modernity began, people have complained about airborne dust – but the measures required to control it have come decades or centuries after, if at all. The coalmines and factories that powered Britain’s Industrial Revolution made a capitalist class very rich, while the cost was borne by their workers in their bodies, lungs and blood. The Ethics of Dust was, for me, about human presence made present – about the building rewritten as not only limestone and glass and a wood-beamed roof, or as big abstract nouns like history and tradition and power, but the material traces of millions of bodies, their labours and their livelihoods. It brings the polis, the people, right into the heart of parliament – and it brings a reckoning with the source of Britain’s historical prosperity, too. In one of India’s most chilling hate crimes, a Railway Protection Force jawan named Chetansinh Chaudhary shot four train passengers dead on July 31. Three of those people were Muslim. Chaudhary had roamed through the train he had been entrusted to protect, hunting for people who looked Muslim, asked for their names and then pumped bullets into them. In the middle of this terror rampage, Chaudhary also

In one of India’s most chilling hate crimes, a Railway Protection Force jawan named Chetansinh Chaudhary shot four train passengers dead on July 31. Three of those people were Muslim. Chaudhary had roamed through the train he had been entrusted to protect, hunting for people who looked Muslim, asked for their names and then pumped bullets into them. In the middle of this terror rampage, Chaudhary also  B

B In 1940, that great and idiosyncratic French philosopher Simone Weil published an essay on the Iliad as “the poem of force”. Despite a grating and drastically misconceived couple of paragraphs contrasting it with the imaginative world of Hebrew scripture, the essay has a good claim to be the most penetrating reflection on Homer’s masterpiece written in the 20th century, and still conveys an exceptional sense of moral and intellectual concentration.

In 1940, that great and idiosyncratic French philosopher Simone Weil published an essay on the Iliad as “the poem of force”. Despite a grating and drastically misconceived couple of paragraphs contrasting it with the imaginative world of Hebrew scripture, the essay has a good claim to be the most penetrating reflection on Homer’s masterpiece written in the 20th century, and still conveys an exceptional sense of moral and intellectual concentration. Summer in New Orleans is a long slow thing. Day and night, a heavy heat presides. Waiters stand idle at outdoor cafés, fanning themselves with menus. The tourists have disappeared, and the city’s main industry has gone with them. Throughout town the pinch is on. It is time to close the shutters and tie streamers to your air conditioner; to lie around and plot ways of scraping by that do not involve standing outside for periods of any length.

Summer in New Orleans is a long slow thing. Day and night, a heavy heat presides. Waiters stand idle at outdoor cafés, fanning themselves with menus. The tourists have disappeared, and the city’s main industry has gone with them. Throughout town the pinch is on. It is time to close the shutters and tie streamers to your air conditioner; to lie around and plot ways of scraping by that do not involve standing outside for periods of any length. A “Darwinian paradox” is that homosexual activity occurs even though it does not lead to or aid in reproduction. But if you visit three capuchin monkeys in Los Angeles, they’ll show you how beneficial their liaisons are.

A “Darwinian paradox” is that homosexual activity occurs even though it does not lead to or aid in reproduction. But if you visit three capuchin monkeys in Los Angeles, they’ll show you how beneficial their liaisons are. Who is Sharon Olds? Sharon Olds is an American poet, born in San Francisco in 1942. She has a Ph.D. in English from Columbia University and made her debut as a writer in 1980 with the poetry collection Satan Says. Since then, she has established herself as one of the most read, most decorated, and most controversial North American contemporary poets. “Sharon Olds’s poems are pure fire in the hands,” Michael Ondaatje has said. She became particularly well known after she refused to take part in a National Book Festival dinner organized by Laura Bush, then First Lady, in 2005, and wrote in an open letter: “So many Americans who had felt pride in our country now feel anguish and shame, for the current regime of blood, wounds and fire. I thought of the clean linens at your table, the shining knives and the flames of the candles, and I could not stomach it.”

Who is Sharon Olds? Sharon Olds is an American poet, born in San Francisco in 1942. She has a Ph.D. in English from Columbia University and made her debut as a writer in 1980 with the poetry collection Satan Says. Since then, she has established herself as one of the most read, most decorated, and most controversial North American contemporary poets. “Sharon Olds’s poems are pure fire in the hands,” Michael Ondaatje has said. She became particularly well known after she refused to take part in a National Book Festival dinner organized by Laura Bush, then First Lady, in 2005, and wrote in an open letter: “So many Americans who had felt pride in our country now feel anguish and shame, for the current regime of blood, wounds and fire. I thought of the clean linens at your table, the shining knives and the flames of the candles, and I could not stomach it.” “Barbenheimer saves cinema!” declared a Daily Mail headline in late July. The tabloid wasn’t the only publication wildly exaggerating the impact of the summer blockbuster releases Barbie and Oppenheimer: two very different works appealing to very different audiences, both released on 21 July, that

“Barbenheimer saves cinema!” declared a Daily Mail headline in late July. The tabloid wasn’t the only publication wildly exaggerating the impact of the summer blockbuster releases Barbie and Oppenheimer: two very different works appealing to very different audiences, both released on 21 July, that  Morgan Meis: Borromini is a name probably not immediately familiar to your average reader. Can we start with a brief explanation of who he was and why his work is of interest?

Morgan Meis: Borromini is a name probably not immediately familiar to your average reader. Can we start with a brief explanation of who he was and why his work is of interest? Memory doesn’t represent a single scientific mystery; it’s many of them. Neuroscientists and psychologists have come to recognize varied types of memory that coexist in our brain: episodic memories of past experiences, semantic memories of facts, short- and long-term memories, and more. These often have different characteristics and even seem to be located in different parts of the brain. But it’s never been clear what feature of a memory determines how or why it should be sorted in this way.

Memory doesn’t represent a single scientific mystery; it’s many of them. Neuroscientists and psychologists have come to recognize varied types of memory that coexist in our brain: episodic memories of past experiences, semantic memories of facts, short- and long-term memories, and more. These often have different characteristics and even seem to be located in different parts of the brain. But it’s never been clear what feature of a memory determines how or why it should be sorted in this way.