(Note: Thanks to Kevin Ham)

Category: Recommended Reading

Liberalism in Mourning

Samuel Moyn in Boston Review:

Samuel Moyn in Boston Review:

Cold War liberalism was a catastrophe—for liberalism. This distinct body of liberal thought says that freedom comes first, that the enemies of liberty are the first priority to confront and contain in a dangerous world, and that demanding anything more from liberalism is likely to lead to tyranny.

This set of ideas became intellectually trendsetting in the 1940s and 1950s at the outset of the Cold War, when liberals conceived of them as essential truths the free world had to preserve in a struggle against totalitarian empire. By the 1960s it had its enemies, who invented the phrase “Cold War liberalism” itself to indict its domestic compromises and foreign policy mistakes. That did not stop it from being rehabilitated in the 1990s, when it was repurposed for a post-political age. A generation of public intellectuals—among them Anne Applebaum, Timothy Garton Ash, Michael Ignatieff, Leon Wieseltier, and many others—styled themselves as successors to Cold War liberals, trumpeting the superiority of Cold War liberalism over illiberal right and left while obscuring just how distinctive it was within the broader liberal tradition. 1989 ushered in the global triumph of freedom, but on Cold War liberalism’s distorted terms.

Then came the election of Donald Trump in 2016, which unleashed a great war over liberalism—a polemical one, at least—and prompted yet another resurgence of Cold War liberalism’s core ideas. Patrick Deneen’s much-discussed assault, Why Liberalism Failed (2018), was met by a crop of liberal self-defenses, almost all of them explicitly or implicitly attempted in Cold War terms. Francis Fukuyama, Adam Gopnik, and Mark Lilla all wrote book-length versions of why Cold War liberalism still had legs, but literally thousands of essays and websites, and even whole magazines such as The Atlantic, offered the same message in frantic response to Trump’s breakthrough. Organized as much against the left as the right, these defenses not only rang hollow; they have failed to forestall the political crisis they promised to transcend.

More here.

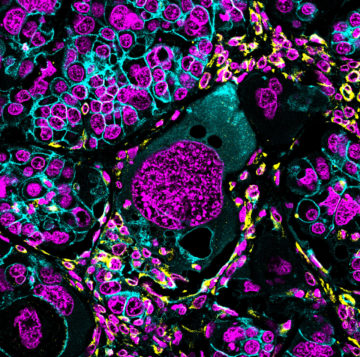

Stress Responders: Giant Polyploid Cells

Elizabeth Pennisi in Science:

When Vicki Losick got her Ph.D. and joined a fruit fly lab at the Carnegie Institution for Science in 2008, its head announced that he expected his postdocs to launch new fields of inquiry. She chose a then-fashionable focus: stem cells, versatile cells that specialize into other cell types and play critical roles in embryonic development and the renewal of adult tissues. Losick wondered whether they also help in wound repair. So, she and another postdoc, Don Fox, began stabbing fruit flies with a tiny needle, hoping to document stem cells coming to the rescue.

Instead, the two postdocs, working independently, saw other cells near the wounds behaving oddly. The cells grew and prepared to divide by duplicating their DNA. Then they stalled, each remaining a single, enlarged cell with multiple copies of its genome. “I was shocked,” recalls Losick, now at Boston College. When she and Fox looked at the fly wound sites a few days later, they saw signs that these so-called polyploid cells, and not stem cells, were the major wound healers. At the puncture site, supersize cells with multiple nuclei quickly closed up the wound. “Simultaneously we found the same thing [and it] had nothing to do with stem cells,” Fox recalls.

More here.

Friday, September 1, 2023

Consciousness is a great mystery, but its definition isn’t

Eric Hoel in The Intrinsic Perspective:

There’s an unkillable myth that the very definition of the word “consciousness” is somehow so slippery, so bedeviled with problems, that we must first specify what we mean out of ten different notions. When this definitional objection is raised, its implicit point is often—not always, but often—that the people who wish to study consciousness scientifically (or philosophically) are so fundamentally confused they can’t even agree on a definition. And if a definition cannot be agreed upon, we should question whether there is anything to say at all.

Unfortunately, this “argument from undefinability” shows up regularly among a certain set of well-educated people. Just to given an example, there was recently an interesting LessWrong post wherein the writer reported on his attempts to ask people to define consciousness, from a group of:

Mostly academics I met in grad school, in cognitive science, AI, ML, and mathematics.

He found that such people would regularly conflate “consciousness” with things like introspection, purposefulness, pleasure and pain, intelligence, and so on. These sort of conflations being common is my impression as well, as I run into them whenever I have given public talks about the neuroscience of consciousness, and I too have found it most prominent among those with a computer science, math, or tech background. It is especially prominent right now amid AI researchers.

So I am here to say that, at least linguistically, “consciousness” is well-defined, and that this isn’t really a matter of opinion.

More here.

Why Mathematical Proof Is a Social Compact

Jordana Cepelewicz in Quanta:

In 2012, the mathematician Shinichi Mochizuki claimed he had solved the abc conjecture, a major open question in number theory about the relationship between addition and multiplication. There was just one problem: His proof, which was more than 500 pages long, was completely impenetrable. It relied on a snarl of new definitions, notation, and theories that nearly all mathematicians found impossible to make sense of. Years later, when two mathematicians translated large parts of the proof into more familiar terms, they pointed to what one called a “serious, unfixable gap” in its logic — only for Mochizuki to reject their argument on the basis that they’d simply failed to understand his work.

In 2012, the mathematician Shinichi Mochizuki claimed he had solved the abc conjecture, a major open question in number theory about the relationship between addition and multiplication. There was just one problem: His proof, which was more than 500 pages long, was completely impenetrable. It relied on a snarl of new definitions, notation, and theories that nearly all mathematicians found impossible to make sense of. Years later, when two mathematicians translated large parts of the proof into more familiar terms, they pointed to what one called a “serious, unfixable gap” in its logic — only for Mochizuki to reject their argument on the basis that they’d simply failed to understand his work.

The incident raises a fundamental question: What is a mathematical proof? We tend to think of it as a revelation of some eternal truth, but perhaps it is better understood as something of a social construct.

More here.

Iran’s street art shows defiance, resistance and resilience

Pouya Afshar in The Conversation:

A recent rise in activism in Iran has added a new chapter to the country’s long-standing history of murals and other public art. But as the sentiments being expressed in those works have changed, the government’s view of them has shifted, too.

A recent rise in activism in Iran has added a new chapter to the country’s long-standing history of murals and other public art. But as the sentiments being expressed in those works have changed, the government’s view of them has shifted, too.

The ancient Persians, who lived in what is now Iran, adorned their palaces, temples and tombs with intricate wall paintings, showcasing scenes of royal court life, religious rituals and epic tales. Following the 1979 revolution and the Iran-Iraq war, murals in Iran took on a new significance and played a crucial role in shaping the national narrative. These murals became powerful visual representations of the ideals and values of the Islamic Republic. They were used to depict scenes of heroism, martyrdom and religious devotion, aiming to inspire national unity and pride among Iranians.

More here.

AI finally beats humans at a real-life sport — drone racing

Consciousness as Complex Event: Towards a New Physicalism

Kelvin J. McQueen at Notre Dame Philosophical Review:

In Consciousness as Complex Event: Towards a New Physicalism, Craig DeLancey argues that what makes conscious (or “phenomenal”) experiences mysterious and seemingly impossible to explain is that they are extremely complex brain events. This is then used to debunk the most influential anti-physicalist arguments, such as the knowledge argument. A new “complexity-based” way of thinking about physicalism is then said to emerge.

In Consciousness as Complex Event: Towards a New Physicalism, Craig DeLancey argues that what makes conscious (or “phenomenal”) experiences mysterious and seemingly impossible to explain is that they are extremely complex brain events. This is then used to debunk the most influential anti-physicalist arguments, such as the knowledge argument. A new “complexity-based” way of thinking about physicalism is then said to emerge.

Brain complexity has been appealed to before, to try to explain why consciousness seems so intractable. What makes DeLancey’s approach distinctive is two-fold. First, DeLancey does not use some vague and informal notion of complexity. Instead, he uses the formal notion of Kolmogorov complexity, which he refers to as descriptive complexity. Second, this notion is intended to do most of the heavy lifting. In particular, DeLancey is clear that he does not wish to supplement his complexity-based defense of physicalism with other existing strategies (the phenomenal concepts strategy, the ability hypothesis, knowledge by acquaintance etc. (23)). The central claim is that “what makes a phenomenal experience mysterious is its [descriptive] complexity” (21).

more here.

Goodbye, Eastern Europe: An Intimate History of a Divided Land

Piotr Florczyk at The American Scholar:

The opening sentence of Jacob Mikanowski’s sweeping history of Eastern Europe—“a place,” he asserts, “that doesn’t exist”—calls to mind a seminal 1983 essay by the recently deceased Czech-French novelist, Milan Kundera. In A Kidnapped West: A Tragedy of Central Europe, Kundera reminded his readers that Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia were historically and culturally closer to the West than to the Soviet East, and should therefore be thought of as central rather than eastern European. Alas, his appeal fell on deaf ears, and the region remains “eastern,” shorthand for a place where, rumor has it, nobody smiles and the smell of burned cabbage wafts through the corridors of charmless, concrete apartment blocks. Indeed, western prejudice was never more in evidence than during the early days of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, when many commentators painted the war as just another incomprehensible scuffle in the other Europe, among the denizens of lands once obscured by the Iron Curtain.

The opening sentence of Jacob Mikanowski’s sweeping history of Eastern Europe—“a place,” he asserts, “that doesn’t exist”—calls to mind a seminal 1983 essay by the recently deceased Czech-French novelist, Milan Kundera. In A Kidnapped West: A Tragedy of Central Europe, Kundera reminded his readers that Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia were historically and culturally closer to the West than to the Soviet East, and should therefore be thought of as central rather than eastern European. Alas, his appeal fell on deaf ears, and the region remains “eastern,” shorthand for a place where, rumor has it, nobody smiles and the smell of burned cabbage wafts through the corridors of charmless, concrete apartment blocks. Indeed, western prejudice was never more in evidence than during the early days of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, when many commentators painted the war as just another incomprehensible scuffle in the other Europe, among the denizens of lands once obscured by the Iron Curtain.

more here.

Eastern Europe With Jacob Mikanowski

AI predicts chemicals’ smells from their structures

Sara Reardon in Nature:

An artificial-intelligence system can describe how compounds smell simply by analysing their molecular structures — and its descriptions are often similar to those of trained human sniffers.

An artificial-intelligence system can describe how compounds smell simply by analysing their molecular structures — and its descriptions are often similar to those of trained human sniffers.

The researchers who designed the system used it to list odours, such as ‘fruity’ or ‘grassy’, that correspond to hundreds of chemical structures. This odorous guidebook could help researchers to design new synthetic scents and might provide insights into how the human brain interprets smell. The research is reported today in Science1. Smells are the only type of sensory information that goes directly from the sensory organ — the nose, in this case — to the brain’s memory and emotional centres; the other kinds of sensory input first pass through other brain regions. This direct route explains why scents can evoke specific, intense memories.

“There’s something special about smell,” says neurobiologist Alexander Wiltschko. His start-up company, Osmo in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is a spin-off from Google Research that is trying to design new smelly molecules, or odorants.

More here.

The Song of the Lark by Willa Cather

Friday Poem

The Origins of Utopia

Many people have long felt the desire to do something

With their lives besides consuming goods. They desire

To interact and develop but for this there is no remedy

Calculable in classical economics. This gets me

Wondering. It would be a fine thing, all that flourishing,

Along with everyone else, but also decently private

So as not to burden one’s neighbors with too much noise

Or such a torrent of dumb ideas all at once. Space required

Is also allocated into the general scheme of the better life,

If not the best life, since the latter wedges its dissatisfaction

Into the minds of each of us according to our old desires,

Childhood vistas, incurable heartbreak by the age of sixteen.

It was silly then but also so totally serious that now our leaders

Wage their private warfare, their revenge, and we’re all implicated.

by Darren Bifford

from Numero Cinq Magazine

Thursday, August 31, 2023

The University of Oxford dominated philosophy in the twentieth century

Michael Gibson at City Journal:

In 1963, the philosophers Gilbert Ryle and Isaiah Berlin had lunch with the composer Igor Stravinsky. Ryle, the least famous of the bunch, was the most scathing in his survey of the philosophical landscape. He dubbed the celebrated American pragmatists William James and John Dewey the “Great American Bores.” He condemned the work of French Jesuit Teilhard de Chardin, with its speculation about an emerging world consciousness, as “old teleological pancake.” Then he summed it up in a sweeping crossfire that could serve as the most Oxonian of putdowns: “Every generation or so philosophical progress is set back by the appearance of a ‘genius.’”

What did Ryle have against such geniuses? And is progress in philosophy even possible?

Largely thanks to Ryle and his colleagues, by the 1950s Oxford had ascended to a commanding position in philosophy, at least in the English-speaking world. On the European continent, things were different: German and French philosophers had run headlong down another path. The two broad traditions that emerged from the split after World War I are known as analytic and continental philosophy. The gap between the two styles is vast.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Yejin Choi on AI and Common Sense

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

Over the last year, AI large-language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT have demonstrated a remarkable ability to carry on human-like conversations in a variety of different concepts. But the way these LLMs “learn” is very different from how human beings learn, and the same can be said for how they “reason.” It’s reasonable to ask, do these AI programs really understand the world they are talking about? Do they possess a common-sense picture of reality, or can they just string together words in convincing ways without any underlying understanding? Computer scientist Yejin Choi is a leader in trying to understand the sense in which AIs are actually intelligent, and why in some ways they’re still shockingly stupid.

Over the last year, AI large-language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT have demonstrated a remarkable ability to carry on human-like conversations in a variety of different concepts. But the way these LLMs “learn” is very different from how human beings learn, and the same can be said for how they “reason.” It’s reasonable to ask, do these AI programs really understand the world they are talking about? Do they possess a common-sense picture of reality, or can they just string together words in convincing ways without any underlying understanding? Computer scientist Yejin Choi is a leader in trying to understand the sense in which AIs are actually intelligent, and why in some ways they’re still shockingly stupid.

More here.

John Stuart Mill vs. the Post-Liberals

Richard V Reeves in Persuasion:

One hundred and fifty years ago, John Stuart Mill died in his home in Avignon. His last words were to his step-daughter, Helen Taylor: “You know that I have done my work.”

One hundred and fifty years ago, John Stuart Mill died in his home in Avignon. His last words were to his step-daughter, Helen Taylor: “You know that I have done my work.”

He certainly had. During his 66 years of life, Mill became the preeminent public intellectual of the century, producing definitive works of logic and political economy, founding and editing journals, serving in Parliament, and churning out book reviews, journalism and essays, most famously his 1859 masterpiece, On Liberty. Oh, and he had a day job, too: as one of the most senior bureaucrats in the East India Company.

What is too often forgotten about Mill is that he was as much an activist as an academic. Benjamin Franklin exhorted his followers to “either write something worth reading or do something worth writing.” Mill, like Franklin himself, is among the very few who managed to do both.

More here.

Sabine Hossenfelder: Do your own research, but do it right!

Thursday Poem

Attention Everyone

Gloom is the enemy, even to the end.

The parodies of self-knowledge were embossed by

Gloom inside our eyelids, and the abrasion makes us

weep, for no reason, like a new bride disconsolate in the

nightgown she had sewn so carefully.

The dog comes back from the fields, lumpy with burrs.

I put down my pen and pull them out; it is care

I have taught him to expect. I’ve always said

it would be difficult.

I’m declaring a new regime. Its flag is woven loam.

Its motto is: Love is worth even its own disasters.

Its totem is the worm. We eat our way through grief

and make it richer. We don’t blunt ourselves against stones

—their borders go all the way through. We go around them.

In my new regime Gloom dances by itself, like a sad poet.

Also I will be sending out some letters:

Dear Friends, please come to the party for my new life.

The dog will meet you at the road, barking,

running stiff-legged circles. Pluck one of his burrs and

follow him here. I’ve got lots of good wine. I’m in love,

my new poems are better than my old poems. It’s been

too long since we started over.

The new regime will start when you lift your eyes

from this page. Here it comes.

by William Matthews

from Sleek for the Long Flight

White Pine Press 1972

Hope is The Thing With Feathers – Emily Dickinson

(Note: For dear friend Kevin Ham)

AI Can Now Design Proteins That Behave Like Biological ‘Transistors’

Shelly Fan in Singularity Hub:

We often think of proteins as immutable 3D sculptures. That’s not quite right. Many proteins are transformers that twist and change their shapes depending on biological needs. One configuration may propagate damaging signals from a stroke or heart attack. Another may block the resulting molecular cascade and limit harm.

We often think of proteins as immutable 3D sculptures. That’s not quite right. Many proteins are transformers that twist and change their shapes depending on biological needs. One configuration may propagate damaging signals from a stroke or heart attack. Another may block the resulting molecular cascade and limit harm.

In a way, proteins act like biological transistors—on-off switches at the root of the body’s molecular “computer” determining how it reacts to external and internal forces and feedback. Scientists have long studied these shape-shifting proteins to decipher how our bodies function. But why rely on nature alone? Can we create biological “transistors,” unknown to the biological universe, from scratch? Enter AI. Multiple deep learning methods can already accurately predict protein structures—a breakthrough half a century in the making. Subsequent studies using increasingly powerful algorithms have hallucinated protein structures untethered by the forces of evolution. Yet these AI-generated structures have a downfall: although highly intricate, most are completely static—essentially, a sort of digital protein sculpture frozen in time.

A new study in Science this month broke the mold by adding flexibility to designer proteins. The new structures aren’t contortionists without limits. However, the designer proteins can stabilize into two different forms—think a hinge in either an open or closed configuration—depending on an external biological “lock.” Each state is analogous to a computer’s “0” or “1,” which subsequently controls the cell’s output. “Before, we could only create proteins that had one stable configuration,” said study author Dr. Florian Praetorius at the University of Washington. “Now, we can finally create proteins that move, which should open up an extraordinary range of applications.” Lead author Dr. David Baker has ideas: “From forming nanostructures that respond to chemicals in the environment to applications in drug delivery, we’re just starting to tap into their potential.”

More here.