Taylor McNeil at Tufts Now:

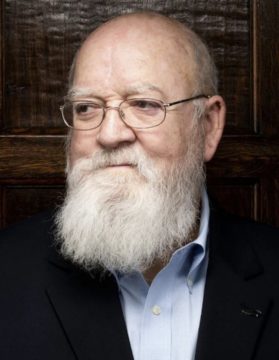

In the book, Dennett describes his intellectual growth and the role he played in many philosophy developments over the years. There’s plenty of inside baseball, but it is lively reading even for those with no stake in the game.

In the book, Dennett describes his intellectual growth and the role he played in many philosophy developments over the years. There’s plenty of inside baseball, but it is lively reading even for those with no stake in the game.

Dennett also devotes a section to academic battles, including what he calls academic bullies, who he often called out when no one else would. “They have ended people’s careers—they have squashed really good people when they disagree with them,” he says. “I was pretty well immune to that, and recognized I should use my relative invulnerability to say what others were saying over drinks in the bar late at night, but didn’t dare say in public.”

More here.

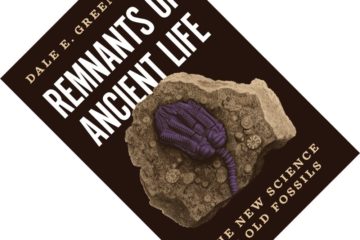

This is the second of a two-part review about ancient biomolecules; think of them as the other fossil evidence. Having just reviewed Jones’s

This is the second of a two-part review about ancient biomolecules; think of them as the other fossil evidence. Having just reviewed Jones’s  Hamas’s brazen and vicious attacks within Israel have rightly drawn condemnation from around the world. If this is a war, as both sides agree it is, then Hamas’s deliberate targeting of civilians counts as a major war crime.

Hamas’s brazen and vicious attacks within Israel have rightly drawn condemnation from around the world. If this is a war, as both sides agree it is, then Hamas’s deliberate targeting of civilians counts as a major war crime. AMONG THE OLDEST REFERENCES to menstruation in literature is in the book of Genesis, in a story about a lie. Rachel stole her father’s household gods, it goes, and when he came to retrieve them, she threw a covering over the objects and sat on it. She couldn’t stand, she apologized to her father, because she was in “the way of women.” At the end of the sixteenth century, an English clergyman clarified in his guide to Genesis that Rachel wasn’t pretending to be incapable of standing, just uncomfortable, due to her “monethly custome,” an ancestor to our contemporary “period.” As Jenni Nuttall explains in her new book Mother Tongue: The Surprising History of Women’s Words, “period” has been in use to name a quantity of time since the Middle Ages, but “only at the end of the seventeenth century”—so, a little after the clergyman’s time—“does the phrase ‘monthly period’ appear in medical books as a name for menstruation.”

AMONG THE OLDEST REFERENCES to menstruation in literature is in the book of Genesis, in a story about a lie. Rachel stole her father’s household gods, it goes, and when he came to retrieve them, she threw a covering over the objects and sat on it. She couldn’t stand, she apologized to her father, because she was in “the way of women.” At the end of the sixteenth century, an English clergyman clarified in his guide to Genesis that Rachel wasn’t pretending to be incapable of standing, just uncomfortable, due to her “monethly custome,” an ancestor to our contemporary “period.” As Jenni Nuttall explains in her new book Mother Tongue: The Surprising History of Women’s Words, “period” has been in use to name a quantity of time since the Middle Ages, but “only at the end of the seventeenth century”—so, a little after the clergyman’s time—“does the phrase ‘monthly period’ appear in medical books as a name for menstruation.” In an

In an  How we grow old gracefully—and whether we can do anything to slow down the process—has long been a fascination of humanity. However, despite continued research the answer to how we can successfully combat aging still remains elusive.

How we grow old gracefully—and whether we can do anything to slow down the process—has long been a fascination of humanity. However, despite continued research the answer to how we can successfully combat aging still remains elusive. Over the last several decades, the rates of new cases of lung cancer have fallen in the United States. There were roughly 65

Over the last several decades, the rates of new cases of lung cancer have fallen in the United States. There were roughly 65  The prize changed our lives. It is the one scientific prize everyone knows. Suddenly you become a public figure being asked to do all sorts of things: to give lectures, quite often on topics you know little about; to sit on committees and reviews you are not always well qualified to be on; to visit countries you have barely heard of; to sign endless petitions on what are probably good causes, but you never know. It is like having a whole new extra job, with upwards of 500 requests a year. It is

The prize changed our lives. It is the one scientific prize everyone knows. Suddenly you become a public figure being asked to do all sorts of things: to give lectures, quite often on topics you know little about; to sit on committees and reviews you are not always well qualified to be on; to visit countries you have barely heard of; to sign endless petitions on what are probably good causes, but you never know. It is like having a whole new extra job, with upwards of 500 requests a year. It is  I have for years been an evangelist for Fosse, who

I have for years been an evangelist for Fosse, who  The 2023 Econ Nobel

The 2023 Econ Nobel  Humans are at war with machines. In the near future, an artificial intelligence defense system detonates a nuclear warhead in Los Angeles. It deploys a formidable army of robots, some of which resemble people. Yet humans still have a shot at victory. So a supersoldier is dispatched on a mission to find the youth who will one day turn the tide in the war.

Humans are at war with machines. In the near future, an artificial intelligence defense system detonates a nuclear warhead in Los Angeles. It deploys a formidable army of robots, some of which resemble people. Yet humans still have a shot at victory. So a supersoldier is dispatched on a mission to find the youth who will one day turn the tide in the war. Since Darwin revealed his seminal theory of evolution by natural selection, human beings have endeavored to understand their own evolutionary origins and history. A lot of questions still remain, but these mainly pertain to the specifics. Today, paleoanthropologists understand in great detail the evolutionary emergence of a number of traits that we consider, at least superficially, unique to modern humans.

Since Darwin revealed his seminal theory of evolution by natural selection, human beings have endeavored to understand their own evolutionary origins and history. A lot of questions still remain, but these mainly pertain to the specifics. Today, paleoanthropologists understand in great detail the evolutionary emergence of a number of traits that we consider, at least superficially, unique to modern humans. Are we living in a simulation? It’s a trippy idea that has inspired many classic tales, from Plato’s Allegory of the Cave to The Matrix franchise, but it is also increasingly becoming a subject of genuine scientific debate and inquiry.

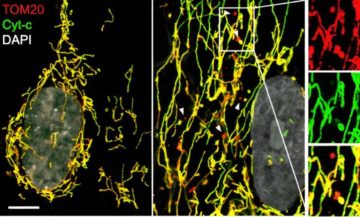

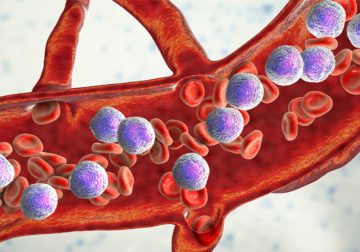

Are we living in a simulation? It’s a trippy idea that has inspired many classic tales, from Plato’s Allegory of the Cave to The Matrix franchise, but it is also increasingly becoming a subject of genuine scientific debate and inquiry. In solid cancers, cellular behaviors such as motility and invasiveness are well characterized contributors to poor prognosis and cancer spread. Scientists pay close attention to a process called

In solid cancers, cellular behaviors such as motility and invasiveness are well characterized contributors to poor prognosis and cancer spread. Scientists pay close attention to a process called  SINCE RUSSIA’S FULL-SCALE INVASION of Ukraine in February 2022, Ukrainian cultural figures have been grappling with Theodor Adorno’s declaration: “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” After the massacre at Bucha, the siege of Mariupol, and the seemingly endless stream of war crimes revealed every time a Ukrainian hamlet is liberated, artists, musicians, and writers are left wondering if they can possibly create something meaningful out of the barbarism—and, perhaps more pertinently, if they should. Theater critic John Freedman’s new anthology A Dictionary of Emotions in a Time of War: 20 Short Works by Ukrainian Playwrights is a response to this question.

SINCE RUSSIA’S FULL-SCALE INVASION of Ukraine in February 2022, Ukrainian cultural figures have been grappling with Theodor Adorno’s declaration: “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” After the massacre at Bucha, the siege of Mariupol, and the seemingly endless stream of war crimes revealed every time a Ukrainian hamlet is liberated, artists, musicians, and writers are left wondering if they can possibly create something meaningful out of the barbarism—and, perhaps more pertinently, if they should. Theater critic John Freedman’s new anthology A Dictionary of Emotions in a Time of War: 20 Short Works by Ukrainian Playwrights is a response to this question. For more than a century, researchers have known that people are generally very good at eyeballing quantities of four or fewer items. But performance at sizing up numbers drops markedly — becoming slower and more prone to error — in the face of larger numbers.

For more than a century, researchers have known that people are generally very good at eyeballing quantities of four or fewer items. But performance at sizing up numbers drops markedly — becoming slower and more prone to error — in the face of larger numbers.