Moonlight

The seasons they are turning

And my sad heart is yearning

To hear again the songbird’s sweet melodious tone

Won’t you meet me out in the moonlight alone?

The dusky light the day is losing

Orchids, poppies, black eyed Susan

The earth and sky that melts with flesh and bone

Won’t you meet me out in the moonlight alone?

The air is thick and heavy

All along the levee

Where the geese into the countryside have flown

Won’t you meet me out in the moonlight alone?

Well, I’m preaching peace and harmony

The blessings of tranquility

Yet I know when the time is right to strike

I take you ‘cross the river, dear

You’ve no need to linger here

I know the kinds of things you like

The clouds are turning crimson

The leaves fall from the limbs

The branches cast their shadows over stone

Won’t you meet me out in the moonlight alone?

The boulevards of cypress trees

The masquerade of birds and bees

The petals pink and white, the wind has blown

Won’t you meet me out in the moonlight alone?

Now trailing moss in mystic glow

The purple blossom soft as snow

My tears keep flowing to the sea

Doctor, lawyer, Indian chief, it takes a thief to catch a thief

For whom does the bell toll for, love?

It tolls for you and me

Old pulse’s running through my palm

The sharp hills are rising from

Yellow fields with twisted oaks that grow

Won’t you meet me out in the moonlight alone?

Bob Dylan

from Love and Theft

album, 2001

The parting gift, I expect, of the bankrupt liberalism of the Democratic Party will be a Christianized fascist state. The liberal class, a creature of corporate power, captive to the war industry and the security state, unable or unwilling to ameliorate the prolonged economic insecurity and misery of the working class, blinded by a self-righteous woke ideology that reeks of hypocrisy and disingenuousness and bereft of any political vision, is the bedrock on which the Christian fascists, who have coalesced in cult-like mobs around Donald Trump, have built their terrifying movement.

The parting gift, I expect, of the bankrupt liberalism of the Democratic Party will be a Christianized fascist state. The liberal class, a creature of corporate power, captive to the war industry and the security state, unable or unwilling to ameliorate the prolonged economic insecurity and misery of the working class, blinded by a self-righteous woke ideology that reeks of hypocrisy and disingenuousness and bereft of any political vision, is the bedrock on which the Christian fascists, who have coalesced in cult-like mobs around Donald Trump, have built their terrifying movement.

The 20-year-old has become one of the world’s best-known campaigners against climate change. She first learned about climate change when she was eight. At the age of 11 or 12, she started suffering from depression, according to her father, Svante: “She stopped talking… she stopped going to school,” he said. Around the same time she was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, a form of autism.

The 20-year-old has become one of the world’s best-known campaigners against climate change. She first learned about climate change when she was eight. At the age of 11 or 12, she started suffering from depression, according to her father, Svante: “She stopped talking… she stopped going to school,” he said. Around the same time she was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, a form of autism. Hamas’ attack on Israel this weekend—including the indiscriminate murder of Israelis—has led to a spiraling of an already dire situation in the region. The recent declaration of war, and the subsequent military actions in Gaza, has set off a crisis in an already calamitous conflict, particularly for the 2 million Gazans—half of whom are children—who have been living in one of the mostly densely populated places on Earth. The

Hamas’ attack on Israel this weekend—including the indiscriminate murder of Israelis—has led to a spiraling of an already dire situation in the region. The recent declaration of war, and the subsequent military actions in Gaza, has set off a crisis in an already calamitous conflict, particularly for the 2 million Gazans—half of whom are children—who have been living in one of the mostly densely populated places on Earth. The  A blood draw is one the most mundane clinical tests. It can also be a Rosetta stone for decoding genetic information and linking DNA typos to health and disease. This week,

A blood draw is one the most mundane clinical tests. It can also be a Rosetta stone for decoding genetic information and linking DNA typos to health and disease. This week,  The short film is a neglected form of American entertainment, prevalent — you can find them most anywhere, and pretty much every filmmaker

The short film is a neglected form of American entertainment, prevalent — you can find them most anywhere, and pretty much every filmmaker  Imagine a nanocrystal so minuscule that it behaves like an atom.

Imagine a nanocrystal so minuscule that it behaves like an atom.  Dread gives way to the cold stab of terrible certainty as it hits you: they aren’t people. They’re bots. The Internet is all bots. Under your nose, the Internet of real people has gradually shifted into a digital world of shadow puppets. They look like people, they act like people, but there are no people left. Well, there’s you and maybe a few others, but you can’t tell the difference, because the bots wear a million masks. You might be alone, and have been for a while. It’s a horror worse than blindness: the certainty that your vision is clear but there is no genuine world to be seen.

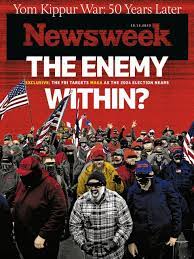

Dread gives way to the cold stab of terrible certainty as it hits you: they aren’t people. They’re bots. The Internet is all bots. Under your nose, the Internet of real people has gradually shifted into a digital world of shadow puppets. They look like people, they act like people, but there are no people left. Well, there’s you and maybe a few others, but you can’t tell the difference, because the bots wear a million masks. You might be alone, and have been for a while. It’s a horror worse than blindness: the certainty that your vision is clear but there is no genuine world to be seen. The federal government believes that the threat of violence and major civil disturbances around the 2024 U.S. presidential election is so great that it has quietly created a new category of extremists that it seeks to track and counter:

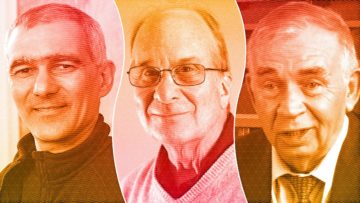

The federal government believes that the threat of violence and major civil disturbances around the 2024 U.S. presidential election is so great that it has quietly created a new category of extremists that it seeks to track and counter:  On July 16, 1945, J. Robert Oppenheimer stood in the Jornada del Muerto desert in New Mexico, watching a second sunrise—that caused by the detonation of the world’s first nuclear explosion, marking the dawn of the atomic age. Standing by his side was I.I. Rabi, another Jewish physicist. “It was a vision,” Rabi later said of that explosion. “Then, a few minutes afterward, I had gooseflesh all over me when I realized what this meant for the future of humanity.” If Oppenheimer was the Jewish father of the bomb, it had a large assortment of Jewish uncles (and at least one aunt, Lise Meitner), including Edward Teller, Leo Szilard, Niels Bohr, Felix Bloch, Hans Bethe, John von Neuman, Rudolf Peierls, Franz Eugene Simon, Hans Halban, Joseph Rotblatt, Stanislav Ulam, Richard Feynman, and Eugene Wigner.

On July 16, 1945, J. Robert Oppenheimer stood in the Jornada del Muerto desert in New Mexico, watching a second sunrise—that caused by the detonation of the world’s first nuclear explosion, marking the dawn of the atomic age. Standing by his side was I.I. Rabi, another Jewish physicist. “It was a vision,” Rabi later said of that explosion. “Then, a few minutes afterward, I had gooseflesh all over me when I realized what this meant for the future of humanity.” If Oppenheimer was the Jewish father of the bomb, it had a large assortment of Jewish uncles (and at least one aunt, Lise Meitner), including Edward Teller, Leo Szilard, Niels Bohr, Felix Bloch, Hans Bethe, John von Neuman, Rudolf Peierls, Franz Eugene Simon, Hans Halban, Joseph Rotblatt, Stanislav Ulam, Richard Feynman, and Eugene Wigner. NEARLY ALL REVOLUTIONS

NEARLY ALL REVOLUTIONS The 2023 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences — the ‘economics Nobel’ — has been awarded to economic historian Claudia Goldin at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, “for having advanced our understanding of women’s labour market outcomes”. Goldin’s work has helped to explain why women have been under-represented in the labour market for at least the past two centuries, and why even today they continue to earn less than men on average (by around 13%).

The 2023 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences — the ‘economics Nobel’ — has been awarded to economic historian Claudia Goldin at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, “for having advanced our understanding of women’s labour market outcomes”. Goldin’s work has helped to explain why women have been under-represented in the labour market for at least the past two centuries, and why even today they continue to earn less than men on average (by around 13%). Jhumpa Lahiri, 56, is the author and translator of three story collections, including the Pulitzer prize-winning Interpreter of Maladies, and three novels,

Jhumpa Lahiri, 56, is the author and translator of three story collections, including the Pulitzer prize-winning Interpreter of Maladies, and three novels, To catch a glimpse of the subatomic world’s unimaginably fleet-footed particles, you need to produce unimaginably brief flashes of light. Anne L’Huillier, Pierre Agostini and Ferenc Krausz have shared the

To catch a glimpse of the subatomic world’s unimaginably fleet-footed particles, you need to produce unimaginably brief flashes of light. Anne L’Huillier, Pierre Agostini and Ferenc Krausz have shared the  H

H