Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

David Deutsch is one of the most creative scientific thinkers working today, who has as a goal to understand and explain the natural world as best we can. He was a pioneer in quantum computing, and has long been an advocate of the Everett interpretation of quantum theory. He is also the inventor of constructor theory, a new way of conceptualizing physics and science more broadly. But he also has a strong interest in philosophy and epistemology, championing a Popperian explanation-based approach over a rival Bayesian epistemology. We talk about all of these things and more, including his recent work on the Popper-Miller theorem, which specifies limitations on inductive approaches to knowledge and probability.

David Deutsch is one of the most creative scientific thinkers working today, who has as a goal to understand and explain the natural world as best we can. He was a pioneer in quantum computing, and has long been an advocate of the Everett interpretation of quantum theory. He is also the inventor of constructor theory, a new way of conceptualizing physics and science more broadly. But he also has a strong interest in philosophy and epistemology, championing a Popperian explanation-based approach over a rival Bayesian epistemology. We talk about all of these things and more, including his recent work on the Popper-Miller theorem, which specifies limitations on inductive approaches to knowledge and probability.

More here.

What happens when lonely men, embittered by a sense of failure in the sexual marketplace, find each other and form communities on the internet? The result can be deadly.

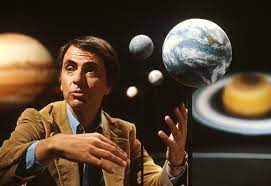

What happens when lonely men, embittered by a sense of failure in the sexual marketplace, find each other and form communities on the internet? The result can be deadly. Early in 1993, a manuscript landed in the Nature offices announcing the results of an unusual — even audacious — experiment. The investigators, led by planetary scientist and broadcaster Carl Sagan, had searched for evidence of life on Earth that could be detected from space. The results, published 30 years ago this week, were “strongly suggestive” that the planet did indeed host life. “These observations constitute a control experiment for the search for extraterrestrial life by modern interplanetary spacecraft,” the team wrote (

Early in 1993, a manuscript landed in the Nature offices announcing the results of an unusual — even audacious — experiment. The investigators, led by planetary scientist and broadcaster Carl Sagan, had searched for evidence of life on Earth that could be detected from space. The results, published 30 years ago this week, were “strongly suggestive” that the planet did indeed host life. “These observations constitute a control experiment for the search for extraterrestrial life by modern interplanetary spacecraft,” the team wrote ( Last week the literary association

Last week the literary association

“It’s not the easiest book in the world to write, but it’s something I need to get past in order to do anything else. I can’t really start writing a novel that’s got nothing to do with this,” he said. “So I just have to deal with it.”

“It’s not the easiest book in the world to write, but it’s something I need to get past in order to do anything else. I can’t really start writing a novel that’s got nothing to do with this,” he said. “So I just have to deal with it.” RELATIONS BETWEEN the United States and China have taken a dark and perilous turn. For much of this century, there was reason to hope that China could be welcomed into the liberal international order, and that its thriving there might mitigate the unavoidable tensions of great power politics. Recently, however, positions have hardened in both East and West. China has taken a discouraging, repressive turn towards personalist authoritarianism; in the United States, increasingly illiberal and politically dysfunctional, a more hawkish posture towards the People’s Republic is one of the vanishingly rare postures that garners bipartisan support in Washington.*

RELATIONS BETWEEN the United States and China have taken a dark and perilous turn. For much of this century, there was reason to hope that China could be welcomed into the liberal international order, and that its thriving there might mitigate the unavoidable tensions of great power politics. Recently, however, positions have hardened in both East and West. China has taken a discouraging, repressive turn towards personalist authoritarianism; in the United States, increasingly illiberal and politically dysfunctional, a more hawkish posture towards the People’s Republic is one of the vanishingly rare postures that garners bipartisan support in Washington.* I had read a few of the novels of Herta Müller with their bleak depictions of a world of social deceptions and betrayals, of people losing their humanity under an inhuman system. “The ant is carrying a dead fly three times its size. The ant can’t see the way ahead, it flips the fly around and crawls back.” Eviscerations of the private life; victim and perpetrator one Janus face. This was a nightmare vision, not a tragic vision, as Claudio Magris put it about so much modern literature of mitteleuropa. But she had left Romania in the 80s and never returned. Then there was the Romanian philosopher, Emil Cioran, one of Susan Sontag’s favorites. He had climbed “the heights of despair,” the title of one of his early books, in 1934. Unsurprisingly, he reached further dismal “heights” through the decades that followed. But then again Cioran, on further study, turned out to be a self-proclaimed “Hitlerist” aligned with the Iron Guard (Romanian fascists), who had left Romania for France in the forties. They had not seen the democratic outpouring just a year before my visit, when crowds had taken to the streets to protest government corruption. The parliament had had the gall to legalize low-level graft and fire the judges who challenged it, but the rallies had shamed them, at least for awhile. (The PSD turned hoses full force on demonstrators, injuring hundreds; but the real news, I want to believe, is that the crowds were back again the next night.)

I had read a few of the novels of Herta Müller with their bleak depictions of a world of social deceptions and betrayals, of people losing their humanity under an inhuman system. “The ant is carrying a dead fly three times its size. The ant can’t see the way ahead, it flips the fly around and crawls back.” Eviscerations of the private life; victim and perpetrator one Janus face. This was a nightmare vision, not a tragic vision, as Claudio Magris put it about so much modern literature of mitteleuropa. But she had left Romania in the 80s and never returned. Then there was the Romanian philosopher, Emil Cioran, one of Susan Sontag’s favorites. He had climbed “the heights of despair,” the title of one of his early books, in 1934. Unsurprisingly, he reached further dismal “heights” through the decades that followed. But then again Cioran, on further study, turned out to be a self-proclaimed “Hitlerist” aligned with the Iron Guard (Romanian fascists), who had left Romania for France in the forties. They had not seen the democratic outpouring just a year before my visit, when crowds had taken to the streets to protest government corruption. The parliament had had the gall to legalize low-level graft and fire the judges who challenged it, but the rallies had shamed them, at least for awhile. (The PSD turned hoses full force on demonstrators, injuring hundreds; but the real news, I want to believe, is that the crowds were back again the next night.) The curators have wisely given the exhibition a chronological hang which allows the viewer to see clearly just how much Guston’s art changed. His paintings of the 1930s and 1940s started in crisp-edged European modernism – with Picasso prominent – and moved into American social realism. He painted murals under the auspices of the New Deal Federal Art Project and works of social and political commentary. In Sunday Interior (1941), for example, he created a potent image of the marginalised – a young black man smoking against the background of an empty street. With Bombardment (1937), a tondo of explosions and hurtling bodies, he expressed his horror at the fascist bombing of the town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War, the subject also of Picasso’s most celebrated work.

The curators have wisely given the exhibition a chronological hang which allows the viewer to see clearly just how much Guston’s art changed. His paintings of the 1930s and 1940s started in crisp-edged European modernism – with Picasso prominent – and moved into American social realism. He painted murals under the auspices of the New Deal Federal Art Project and works of social and political commentary. In Sunday Interior (1941), for example, he created a potent image of the marginalised – a young black man smoking against the background of an empty street. With Bombardment (1937), a tondo of explosions and hurtling bodies, he expressed his horror at the fascist bombing of the town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War, the subject also of Picasso’s most celebrated work. In a since-deleted thread on the messaging platform X, the

In a since-deleted thread on the messaging platform X, the  Many use the word solidarity when describing a bond with friends, coworkers, and teammates, but I like to apply the word when describing a fight for shared interests between different types of people, whether it be the battle against racism, LGBTQ+ rights, and labor—solidarity speaks of unity. “When one wins, we all win. When one dies, we all die.” Those words from older activists echo loud today. As a Black man in America, I feel empathy for the people of Palestine. I stand with them. Like millions around the world, I have been focused on the war between Israel and Hamas. What started out as a retaliation for

Many use the word solidarity when describing a bond with friends, coworkers, and teammates, but I like to apply the word when describing a fight for shared interests between different types of people, whether it be the battle against racism, LGBTQ+ rights, and labor—solidarity speaks of unity. “When one wins, we all win. When one dies, we all die.” Those words from older activists echo loud today. As a Black man in America, I feel empathy for the people of Palestine. I stand with them. Like millions around the world, I have been focused on the war between Israel and Hamas. What started out as a retaliation for  Travelers to Unimaginable Lands is that rarity: true biblio-therapy. Lucid, mature, wise, with hardly a wasted word, it not only deepens our understanding of what transpires as we care for a loved one with Alzheimer’s, it also has the potential to be powerfully therapeutic, offering the kind of support and reorientation so essential to the millions of people struggling with the long, often agonizing leave-taking of loved ones stricken with the dreaded disease. The book is based on a profound insight: the concept of “dementia blindness,” which identifies a singular problem of caring for people with dementia disorders—one that has generally escaped notice but, once understood, may make a significant difference for many caregivers.

Travelers to Unimaginable Lands is that rarity: true biblio-therapy. Lucid, mature, wise, with hardly a wasted word, it not only deepens our understanding of what transpires as we care for a loved one with Alzheimer’s, it also has the potential to be powerfully therapeutic, offering the kind of support and reorientation so essential to the millions of people struggling with the long, often agonizing leave-taking of loved ones stricken with the dreaded disease. The book is based on a profound insight: the concept of “dementia blindness,” which identifies a singular problem of caring for people with dementia disorders—one that has generally escaped notice but, once understood, may make a significant difference for many caregivers. A

A JULIEN CROCKETT: I want to start with a quote from the end of your book where you discuss the final stage of life—death—and what happens with the failures we accumulate along the way:

JULIEN CROCKETT: I want to start with a quote from the end of your book where you discuss the final stage of life—death—and what happens with the failures we accumulate along the way: Husserl’s The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology is widely regarded as both his most accessible and most influential work, written under the shadow of fascist ideology looming over Europe. Based on lectures given in 1935 at Charles University and the German University in Prague, Husserl opens by addressing the ‘Crisis? What crisis?’ question that many in the audience must have been asking themselves:

Husserl’s The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology is widely regarded as both his most accessible and most influential work, written under the shadow of fascist ideology looming over Europe. Based on lectures given in 1935 at Charles University and the German University in Prague, Husserl opens by addressing the ‘Crisis? What crisis?’ question that many in the audience must have been asking themselves: Disputes arising from geopolitical crises occur in numerous social settings, but colleges are especially vulnerable. First, campuses by their nature are (or should be) spaces for robust debate on contested topics, strongly protected by free-speech norms. Second, students and faculty represent diverse nationalities, religions, cultures, and belief systems. Third, college leaders are expected by many to express opinions on political and social issues on behalf of the institution.

Disputes arising from geopolitical crises occur in numerous social settings, but colleges are especially vulnerable. First, campuses by their nature are (or should be) spaces for robust debate on contested topics, strongly protected by free-speech norms. Second, students and faculty represent diverse nationalities, religions, cultures, and belief systems. Third, college leaders are expected by many to express opinions on political and social issues on behalf of the institution.