Melvin Rogers in Lapham’s Quarterly:

Debates about the representation of African Americans circulated throughout the 1920s—what kinds of depictions should be encouraged, who should be responsible for them, and what role black artists had in responding to negative descriptions and uplifting the race. These themes served as the subject of W.E.B. Du Bois’ 1926 symposium, “The Negro in Art: How Shall He Be Portrayed?” hosted in the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis. Even a cursory glance at the responses to Du Bois’ question reveals that few believed African Americans were duty bound to direct their art to the cause of social justice. The unencumbered freedom of the artist, many argued, was far too important. As playwright and novelist Heyward DuBose argues, who himself was not an African American, black people must be “treated artistically. It destroys itself as soon as it is made a vehicle for propaganda. If it carries a moral or a lesson, they should be subordinated to the artistic aim.”

Debates about the representation of African Americans circulated throughout the 1920s—what kinds of depictions should be encouraged, who should be responsible for them, and what role black artists had in responding to negative descriptions and uplifting the race. These themes served as the subject of W.E.B. Du Bois’ 1926 symposium, “The Negro in Art: How Shall He Be Portrayed?” hosted in the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis. Even a cursory glance at the responses to Du Bois’ question reveals that few believed African Americans were duty bound to direct their art to the cause of social justice. The unencumbered freedom of the artist, many argued, was far too important. As playwright and novelist Heyward DuBose argues, who himself was not an African American, black people must be “treated artistically. It destroys itself as soon as it is made a vehicle for propaganda. If it carries a moral or a lesson, they should be subordinated to the artistic aim.”

Du Bois’ essay “Criteria of Negro Art” is his answer to the symposium that he organized. But whereas most read this essay as the dividing line (and there is some truth in this) between Du Bois and many in the Harlem Renaissance, especially the writer and philosopher Alain Locke, the essay suggests closer proximity between these two figures. They each were seeking to avoid black artists needing to manage the unacceptable demands of what Langston Hughes called the “undertow of sharp criticism and misunderstanding” from black people and “unintentional bribes from whites.”

More here.

A

A A Food and Drug Administration (FDA) advisory committee met last week to discuss human trials of artificial wombs, which could one day be used to keep extremely premature, or preterm, infants alive. Artificial wombs have been tested with animals, but never in human clinical trials. The FDA has not approved the technology yet, but the advisory panel discussed the available science, as well as the clinical risks, benefits and ethical considerations of testing artificial wombs with humans.

A Food and Drug Administration (FDA) advisory committee met last week to discuss human trials of artificial wombs, which could one day be used to keep extremely premature, or preterm, infants alive. Artificial wombs have been tested with animals, but never in human clinical trials. The FDA has not approved the technology yet, but the advisory panel discussed the available science, as well as the clinical risks, benefits and ethical considerations of testing artificial wombs with humans. One night in 1981, in the middle of bath time, Marty Gonzalez noticed a strange glow that seemed to emanate from inside one of the eyes of her 9-month-old daughter, Marissa. “It was really bizarre,” Gonzalez recalls. “It looked like a cat’s eye — like I could see all the way through.” Though Marissa’s pediatrician in Long Beach, Calif., assured Gonzalez it was nothing, she sought another opinion. While teaching her sixth-grade class, Gonzalez anxiously awaited news from her mother, who had taken Marissa to see a pediatric ophthalmologist. By lunchtime, with still no word from her mom, Gonzalez called the doctor directly. “I think it’s cancer,” the doctor told her.

One night in 1981, in the middle of bath time, Marty Gonzalez noticed a strange glow that seemed to emanate from inside one of the eyes of her 9-month-old daughter, Marissa. “It was really bizarre,” Gonzalez recalls. “It looked like a cat’s eye — like I could see all the way through.” Though Marissa’s pediatrician in Long Beach, Calif., assured Gonzalez it was nothing, she sought another opinion. While teaching her sixth-grade class, Gonzalez anxiously awaited news from her mother, who had taken Marissa to see a pediatric ophthalmologist. By lunchtime, with still no word from her mom, Gonzalez called the doctor directly. “I think it’s cancer,” the doctor told her. Amy Kapczynski, Reshma Ramachandran and Christopher Morten in Boston Review:

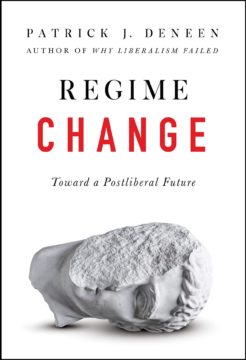

Amy Kapczynski, Reshma Ramachandran and Christopher Morten in Boston Review: Jeffrey C. Isaac in LA Review of Books:

Jeffrey C. Isaac in LA Review of Books: Alvin Camba in Phenomenal World:

Alvin Camba in Phenomenal World: William Callison in Sidecar:

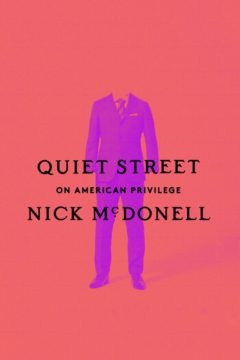

William Callison in Sidecar: IN HIS 1980 ESSAY ON THE AMERICAN SCENE, “Within the Context of No Context,” George W. S. Trow supplies an anecdote from Harvard in the early 1960s. During an art history class on the Dutch masters, a Black student described Rembrandt as “‘belonging’ to the white students in the room.” The white students totally agreed with this. “They acknowledged that they were at one with Rembrandt,” Trow writes. “They acknowledged their dominance. They offered to discuss, at any length, their inherited power to oppress.”

IN HIS 1980 ESSAY ON THE AMERICAN SCENE, “Within the Context of No Context,” George W. S. Trow supplies an anecdote from Harvard in the early 1960s. During an art history class on the Dutch masters, a Black student described Rembrandt as “‘belonging’ to the white students in the room.” The white students totally agreed with this. “They acknowledged that they were at one with Rembrandt,” Trow writes. “They acknowledged their dominance. They offered to discuss, at any length, their inherited power to oppress.” Not long ago our mother died, or at least her body did—the rest of her remained obstinately alive. She took a considerable time to die and outlasted the nurses’ predictions by many days, so that those of us who had been summoned to her bedside had to depart and return to our lives.

Not long ago our mother died, or at least her body did—the rest of her remained obstinately alive. She took a considerable time to die and outlasted the nurses’ predictions by many days, so that those of us who had been summoned to her bedside had to depart and return to our lives. Picture this: the setting sun paints a cornfield in dazzling hues of amber and gold. Thousands of corn stalks, heavy with cobs and rustling leaves, tower over everyone—kids running though corn mazes; farmers examining their crops; and robots whizzing by as they gently pluck ripe, sweet ears for the fall harvest.

Picture this: the setting sun paints a cornfield in dazzling hues of amber and gold. Thousands of corn stalks, heavy with cobs and rustling leaves, tower over everyone—kids running though corn mazes; farmers examining their crops; and robots whizzing by as they gently pluck ripe, sweet ears for the fall harvest. John Waters was kicked out of NYU film school for smoking marijuana. Even that incubator for original filmmakers couldn’t handle him. Now, among people I know, announcing yourself as a graduate of NYU film school is a shorthand for being an uppity, social-climbing brat (I should know, I’m one of them). It’s so much cooler to be John Waters. He’s a degenerate and an iconoclast, making even the most daring artists look like uninspired conformists. In fact, I don’t know anyone who dislikes John Waters. If I did, I would think it was an easy tell that they were boring and had bad sex.

John Waters was kicked out of NYU film school for smoking marijuana. Even that incubator for original filmmakers couldn’t handle him. Now, among people I know, announcing yourself as a graduate of NYU film school is a shorthand for being an uppity, social-climbing brat (I should know, I’m one of them). It’s so much cooler to be John Waters. He’s a degenerate and an iconoclast, making even the most daring artists look like uninspired conformists. In fact, I don’t know anyone who dislikes John Waters. If I did, I would think it was an easy tell that they were boring and had bad sex. A string of job postings from high-profile training data companies, such as

A string of job postings from high-profile training data companies, such as  Deep in Pakistan’s countryside, Sindhi Chhokri and her teenage brother Toxic Sufi are raising a few eyebrows.

Deep in Pakistan’s countryside, Sindhi Chhokri and her teenage brother Toxic Sufi are raising a few eyebrows. In 1978, Kathy Kleiner was asleep in her bed at the Chi Omega sorority house at Florida State University when serial killer Ted Bundy entered through an unlocked door. After attacking two of her sorority sisters, Bundy found Kathy’s door also unlocked.

In 1978, Kathy Kleiner was asleep in her bed at the Chi Omega sorority house at Florida State University when serial killer Ted Bundy entered through an unlocked door. After attacking two of her sorority sisters, Bundy found Kathy’s door also unlocked.  We asked young scientists this question: If you could introduce any two scientists, regardless of where and when they lived, whom would you choose, and how would their collaboration change the course of history? Read a selection of the responses here. Follow NextGen Voices on social media with hashtag #NextGenSci.

We asked young scientists this question: If you could introduce any two scientists, regardless of where and when they lived, whom would you choose, and how would their collaboration change the course of history? Read a selection of the responses here. Follow NextGen Voices on social media with hashtag #NextGenSci.