Category: Recommended Reading

The Diaries Of Franz Kafka

Charlie Tyson at Bookforum:

The complex nature of Kafka’s agony around work is made freshly discernible in Ross Benjamin’s new translation of the author’s diaries. By giving us a more bodily Kafka than has hitherto been available, Benjamin helps us sense the author’s pleasures and pains with greater clarity. As we turn the pages of the diary, we are reminded that the same man who professed that he was “made of literature . . . nothing else” also went swimming, took walks, visited brothels, and, when his digestive troubles lapsed, dreamed of forsaking his carefully masticated vegetarian diet to gorge himself on sausages and “eat dirty grocery stores completely empty.”

The complex nature of Kafka’s agony around work is made freshly discernible in Ross Benjamin’s new translation of the author’s diaries. By giving us a more bodily Kafka than has hitherto been available, Benjamin helps us sense the author’s pleasures and pains with greater clarity. As we turn the pages of the diary, we are reminded that the same man who professed that he was “made of literature . . . nothing else” also went swimming, took walks, visited brothels, and, when his digestive troubles lapsed, dreamed of forsaking his carefully masticated vegetarian diet to gorge himself on sausages and “eat dirty grocery stores completely empty.”

Kafka also looked at pornography, posed nude for another man’s sketch (“Exhibitionistic experience”), noted the “sizable member” bulging in a fellow train passenger’s trousers, and admired the long legs of two lovely Swedish boys, “so formed and taut that one could really only run one’s tongue along them.”

more here.

The Cosmic, Outrageous, Ecstatic Truths of Werner Herzog

Dwight Garner at the NYT:

I don’t believe a word of the filmmaker Werner Herzog’s new memoir, which bears the self-deprecating title “Every Man for Himself and God Against All.” (What is this, a Metallica album?) But then, I’m not sure we’re supposed to take much of it at face value.

I don’t believe a word of the filmmaker Werner Herzog’s new memoir, which bears the self-deprecating title “Every Man for Himself and God Against All.” (What is this, a Metallica album?) But then, I’m not sure we’re supposed to take much of it at face value.

Like Jim Smiley in Mark Twain’s “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County,” and Bob Dylan, and Tom Waits, Herzog is an old-school, concierge-level bluffer. And ham. He won’t tell you the truth, not quite, unless it falls out of his pocket accidentally, as if it were a cigarette lighter.

Speaking about his documentaries, Herzog uses the phrase “ecstatic truth.” When you imagine that phrase uttered in his droll, stoic German accent, it sounds less evangelical, less like something Kellyanne Conway would say.

more here.

Saturday Poem

Those Winter Sundays

Sundays too my father got up early

and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold,

then with cracked hands that ached

from labor in the weekday weather made

banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him.

I’d wake and hear the cold splintering, breaking.

When the rooms were warm, he’d call,

and slowly I would rise and dress,

feeling the chronic angers of that house,

Speaking indifferently to him,

who had driven out the cold

and polished my good shoes as well.

What did I know, what did I know

of love’s austere and lonely offices?

by Robert Hayden

from Literature and the Writing Process

Prentice Hall, 1999

Roman Stories – outsiders in Italy

Yagnishsing Dawoor in The Guardian:

The Bengali-American writer Jhumpa Lahiri’s latest collection is an urgent and affecting portrait of Rome in nine stories featuring characters, both native and non-native, who inhabit the city without ever feeling fully at home. As one remarks, “Rome switches between heaven and hell.” Like Whereabouts, Lahiri’s previous book, this collection was composed in Italian and then translated into English. Lahiri self-translated six out of the nine stories, entrusting editor Todd Portnowitz with the remaining three. The translation is supple and elegant throughout; sentences gleam and flow, adding to the vividness and immediacy of these tales about buried grief, belonging and unbelonging, the meaning of home and the cost of exile.

The Bengali-American writer Jhumpa Lahiri’s latest collection is an urgent and affecting portrait of Rome in nine stories featuring characters, both native and non-native, who inhabit the city without ever feeling fully at home. As one remarks, “Rome switches between heaven and hell.” Like Whereabouts, Lahiri’s previous book, this collection was composed in Italian and then translated into English. Lahiri self-translated six out of the nine stories, entrusting editor Todd Portnowitz with the remaining three. The translation is supple and elegant throughout; sentences gleam and flow, adding to the vividness and immediacy of these tales about buried grief, belonging and unbelonging, the meaning of home and the cost of exile.

The characters, always unnamed, are sick and homesick; they worry about their bodies and they reminisce about past homes and past lives. Sometimes a parent, a friend or a child is remembered or mourned; always, a degree of guilt is involved. In The Procession, set during the festivities of La Festa de Noantri, a couple arrive in Rome to celebrate the wife’s 50th birthday. The city, we learn, holds a special place in her heart; it was where she had studied for a year when she was 19 and where she had fallen in love for the first time. But peace will repeatedly elude her during her stay. Upsetting details accumulate. Morning light that startles “like an electric charge”; a chandelier that threatens to come crashing down. French doors that slam and shatter. A room that will not unlock. Another that brings to mind an operating theatre and a dead son.

More here.

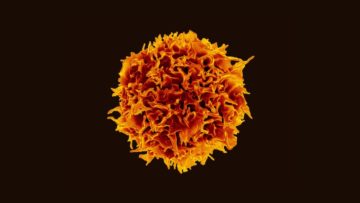

Cancer-Killing Duo Hunts Down and Destroys Tumors With Surprising Alacrity

Shelly Fan in Singularity Hub:

Bacteria may seem like a strange ally in the battle against cancer.

Bacteria may seem like a strange ally in the battle against cancer.

But in a new study, genetically engineered bacteria were part of a tag-team therapy to shrink tumors. In mice with blood, breast, or colon cancer, the bacteria acted as homing beacons for their partners—modified T cells—as the two sought out and destroyed tumor cells. CAR T—the name for therapies using these cancer-destroying T cells—is a transformative approach. First approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for a type of deadly leukemia in 2017, there are now six treatments available for multiple types of blood cancers. Dubbed a “living drug” by pioneer researcher Dr. Carl June at University of Pennsylvania, CAR T is beginning to take on autoimmune diseases, heart injuries, and liver problems. It is also poised to wipe out senescent “zombie cells” linked to age-related diseases and fight off HIV and other viral infections.

Despite its promise, however, CAR T falters when pitted against solid tumors—which make up roughly 90 percent of all cancers. “Each type of tumor has its own little ways of evading the immune system,” said June previously in Penn Medicine News. “So there won’t be one silver-bullet CAR T therapy that targets all types of tumors.” Surprisingly, bacteria may cause June to reconsider—the new approach has potential as a universal treatment for all sorts of solid tumors. When given to mice, the engineered bugs dug deep into the cores of tumors and readily secreted a synthetic “tag” to draw in nearby CAR T soldiers. The molecular tag only sticks to the regions immediately surrounding a tumor and spares healthy cells from CAR T attacks. The engineered bacteria could also, in theory, infiltrate other types of solid tumors, including “sneaky” ones difficult to target with conventional therapies. Together, the new method called ProCAR—probiotic-guided CAR T cells—combines bacteria and T cells into a cancer-fighting powerhouse.

More here.

Friday, October 20, 2023

Confessions of a Tableside Flambéur

Adam Reiner at Eater:

“What’s that thing with the fire?” a woman from the table behind me asks, tugging on the vents of my tuxedo jacket and gesturing toward the dessert I just finished flambéing. I’m tempted to lie and tell her we just sold out, but instead I explain the Bananas Foster — caramelized bananas flamed with dark rum over house-made banana-buttermilk ice cream — the restaurant’s most popular dessert. But she isn’t listening. I can already sense her plans to cast me as the lead in her TikTok video or the poster child for her “en fuego” meme. “Oh my God, I hate bananas,” she says, turning toward her tablemates, “but we should totally order it anyway!” They haven’t even finished their appetizers.

“What’s that thing with the fire?” a woman from the table behind me asks, tugging on the vents of my tuxedo jacket and gesturing toward the dessert I just finished flambéing. I’m tempted to lie and tell her we just sold out, but instead I explain the Bananas Foster — caramelized bananas flamed with dark rum over house-made banana-buttermilk ice cream — the restaurant’s most popular dessert. But she isn’t listening. I can already sense her plans to cast me as the lead in her TikTok video or the poster child for her “en fuego” meme. “Oh my God, I hate bananas,” she says, turning toward her tablemates, “but we should totally order it anyway!” They haven’t even finished their appetizers.

Scenes like this were not uncommon during the three years I worked as a captain at the Grill in midtown Manhattan — a midcentury chophouse in the former Four Seasons Restaurant space where tableside theatrics and culinary sleight of hand are calculated distractions.

More here.

The Fantasy of Energy Independence

Peter Z. Grossman in The New Atlantis:

It has now been fifty years since the oil crisis that began when Arab members of OPEC imposed an embargo on the United States. Announced on October 17, 1973, the ban on oil exports to America was an act of retaliation for our aid to Israel during the Yom Kippur War. The war itself had begun only days earlier when Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack on Israel — the surprise attack on Israel by Hamas just days ago was apparently timed to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the 1973 war.

The embargo discombobulated Americans from the president down to the person on the street. The price of oil soared, there were lines at gas stations, and Americans feared that the use of oil as a geopolitical weapon would be repeated painfully for years.

But the worst effect was on U.S. energy policy. Whereas the embargo lasted about five months, the toll on U.S. policy has lasted five decades and counting. The policy disaster began on November 7, 1973, three weeks after the embargo was announced…

More here.

Eating the New World’s Hottest Pepper: “Pepper X”

The largest-ever survey on fetishes, and what it has to teach us about sex, pleasure, and social science methodology

Aella at Asterisk Magazine:

If you’re new to my work, I’m a self-taught researcher, driven to learn through fortunate access to high sample sizes and sheer curiosity. As of this writing, over 700,000 people have responded to my Big Kink Survey on fetishes and sex — likely one of the largest surveys on the topic ever done. It grew out of my desire to answer two questions: How weird is my own sexuality, exactly? and Why are there way more women interested in submission than men interested in dominance?

If you’re new to my work, I’m a self-taught researcher, driven to learn through fortunate access to high sample sizes and sheer curiosity. As of this writing, over 700,000 people have responded to my Big Kink Survey on fetishes and sex — likely one of the largest surveys on the topic ever done. It grew out of my desire to answer two questions: How weird is my own sexuality, exactly? and Why are there way more women interested in submission than men interested in dominance?

I originally started doing surveys via porn (I also do porn), which is a super easy way to get a lot of horny social media followers willing to do anything you ask them to. I’d ask them to help answer random questions I had, and quickly realized the data was terrible because my questions were terrible.

More here.

End Of The Century: The Story Of The Ramones

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MzbjK4TwW7U&ab_channel=Mr.WildChild01V3.

The Long, Petty Friendship That Changed Art

Jackson Arn at The New Yorker:

The Lippis raise an important point, which “Manet/Degas” can’t help circling back to: great painters are not necessarily good painters. Art lovers, probably overcorrecting for “my kid could do that” philistinism, can be touchy about this, but in the case of Manet, a painter as great as he was technically dubious, it can’t be said too often. In much of his early work, near and far bump against each other—the rainbow in “Fishing” (ca. 1862-63) is as phony as the backdrop for a middle-school play—and his figures never really seem to be standing on solid ground, as though he’s cut them out of someone else’s painting. In the eighteen-sixties, Manet cut out a significant chunk of his own painting, “Episode from a Bullfight,” in response to criticism that he’d botched the perspective. It’s the kind of story you rarely find in art mythology: avant-gardists are supposed to be indifferent to critics, deliberate in their desecrations of tradition. In the case of Manet, the celebrated ur-modernist who made the world safe for flat, unfinished-looking art, it’s extra startling. Surely he, of all people, understood what he’d done.

more here.

Vesuvius in the Age of Revolutions

Seamus Perry at Literary Review:

‘That’s our mountain,’ a wordy Neapolitan told Hester Piozzi, ‘which throws up money for us, by calling foreigners to see the extraordinary effects of so surprising a phenomenon.’ The hermits were only one part of a flourishing and lucrative Vesuvius service industry that visitors encountered as they began their ascents. As Brewer says, what the industry was ‘selling was a sublime experience’. Making your own way up the mountain to see the extraordinary effects was perilous, but help was at hand. Your first encounter upon arrival would be with a disorganised horde of vociferous guides, all offering their services. The spectacle seems to have been distinctly off-putting: the poet Shelley, generally a friend of humanity, thought these particular humans ‘degraded, disgusting & odious’. Degraded or not, some guides became celebrities: Salvatore Madonna (‘il capo cicerone’) was well-known for his narrative skills and general charm, as well as for his knowledge of the territory, and he even appeared in guidebooks as a colourful feature of the scene to be looked out for. Madonna seems to have been a professional type, but untrustworthy guides were not uncommon.

‘That’s our mountain,’ a wordy Neapolitan told Hester Piozzi, ‘which throws up money for us, by calling foreigners to see the extraordinary effects of so surprising a phenomenon.’ The hermits were only one part of a flourishing and lucrative Vesuvius service industry that visitors encountered as they began their ascents. As Brewer says, what the industry was ‘selling was a sublime experience’. Making your own way up the mountain to see the extraordinary effects was perilous, but help was at hand. Your first encounter upon arrival would be with a disorganised horde of vociferous guides, all offering their services. The spectacle seems to have been distinctly off-putting: the poet Shelley, generally a friend of humanity, thought these particular humans ‘degraded, disgusting & odious’. Degraded or not, some guides became celebrities: Salvatore Madonna (‘il capo cicerone’) was well-known for his narrative skills and general charm, as well as for his knowledge of the territory, and he even appeared in guidebooks as a colourful feature of the scene to be looked out for. Madonna seems to have been a professional type, but untrustworthy guides were not uncommon.

more here.

Friday Poem

Two Poems of truth, injustice, & backbone

A Man Said to the Universe

A man said to the universe:

“Sir, I exist!”

“However,” replied the universe,

“The fact has not created in me

A sense of obligation.”

by Stephan Crane 1871-1900

Mother to Son

Well, son, I’ll tell you:

Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.

It’s had tacks in it,

And splinters,

And boards torn up,

And places with no carpet on the floor—

Bare.

But all the time

I’se been a-climbin’ on,

And reachin’ landins’

And turnin’ corners,

And sometimes goin’ in the dark

Where there ain’t been no light.

So boy, don’t you turn back.

Don’t you set down on the steps

‘Cause you finds it’s kinder hard.

Don’t you fall now—

For I’se still goin’, honey,

I’se still climbin’,

And life ain’t been for me no crystal stair.

by Langston Hughes 1902-1967

Airlines say they’ve found a route to climate-friendly flying

Umair Irfan in Vox:

Aviation produces about 2.5 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions. If you add in the heat-trapping effects of water vapor in contrails and other pollutants, air travel accounts for about 4 percent of the warming across the planet induced by humans to date. It may seem like a small slice of the climate change problem, but if left unchecked, aviation’s carbon dioxide emissions are poised to double by 2050. “The biggest problem is that demand is rising,” said Gökçin Çınar, an assistant professor of aerospace engineering at the University of Michigan. Even as aircraft grow more fuel-efficient per passenger, more flyers will lead to more greenhouse gases.

Aviation produces about 2.5 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions. If you add in the heat-trapping effects of water vapor in contrails and other pollutants, air travel accounts for about 4 percent of the warming across the planet induced by humans to date. It may seem like a small slice of the climate change problem, but if left unchecked, aviation’s carbon dioxide emissions are poised to double by 2050. “The biggest problem is that demand is rising,” said Gökçin Çınar, an assistant professor of aerospace engineering at the University of Michigan. Even as aircraft grow more fuel-efficient per passenger, more flyers will lead to more greenhouse gases.

However, decarbonizing aircraft is a huge technical challenge. To get a 400,000-pound airliner off the ground, up to 35,000 feet, and across an ocean, you need to squeeze an enormous amount of energy into a tiny space at the lowest weight possible. This trait is called specific energy, which is measured in watt-hours per kilogram or megajoules per kilogram. The best lithium-ion batteries top out around 300 watt-hours per kilogram. Jet fuel has a specific energy around 12,000 watt-hours per kilogram. And as an airplane burns fuel, it gets lighter, increasing its efficiency and range, whereas a dead battery weighs just as much as a live one. Swapping a gasoline engine for an electric motor in a car is trivial in comparison.

More here.

Can Happiness Be Taught?

Anthony Lane in The New Yorker:

Staring into the mirror, on a Tuesday morning, you decide that your self needs all the help it can get. But where to turn? You were reading James Clear’s “Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones” and doing well until you spilled half a bottle of Knob Creek over the last sixty pages. Now you’ll never know how it ends. You tried listening to David Goggins’s “Can’t Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds,” on Audible, in your car, but so thrilling was Goggins’s prose style that you stomped on the gas and rear-ended a Tesla. Do not despair, though. Succor is at hand. Roosting on Amazon’s best-seller list is “Build the Life You Want: The Art and Science of Getting Happier,” by Arthur C. Brooks and Oprah Winfrey (Portfolio).

Staring into the mirror, on a Tuesday morning, you decide that your self needs all the help it can get. But where to turn? You were reading James Clear’s “Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones” and doing well until you spilled half a bottle of Knob Creek over the last sixty pages. Now you’ll never know how it ends. You tried listening to David Goggins’s “Can’t Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds,” on Audible, in your car, but so thrilling was Goggins’s prose style that you stomped on the gas and rear-ended a Tesla. Do not despair, though. Succor is at hand. Roosting on Amazon’s best-seller list is “Build the Life You Want: The Art and Science of Getting Happier,” by Arthur C. Brooks and Oprah Winfrey (Portfolio).

…When two writers join forces, it can be tricky to sort out who did what. Not in this case. Brooks is the principal player, and Oprah is his guest star. Only four times does she enter the action to offer “A Note from Oprah,” and the four notes, added together, take up less than fourteen pages in a book that is more than two hundred and forty pages long. What does she bring, then, apart from the humongous commercial clout of her blessing? Well, she reveals that “The Oprah Winfrey Show” was “always at heart a classroom. I was curious about so many things, from the intricacies of the digestive system to the meaning of life.” (Had she been French, of course, those two items would have been the same.) Near the start of the book, ever alert to her audience, she scrunches what she considers Brooks’s most valuable lesson into “words you should tape to your refrigerator,” and, for extra clarity, accelerates into italics: “Your emotions are only signals. And you get to decide how you’ll respond to them.” One more scrunch, and Oprah has the mantra she wants: “Feel the feel, then take the wheel.”

More here.

Thursday, October 19, 2023

Weil: Theory, Fiction, and Academia with Lars Iyer

Artificial General Intelligence Is Already Here

Blaise Agüera y Arcas & Peter Norvig at Noema:

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) means many different things to different people, but the most important parts of it have already been achieved by the current generation of advanced AI large language models such as ChatGPT, Bard, LLaMA and Claude. These “frontier models” have many flaws: They hallucinate scholarly citations and court cases, perpetuate biases from their training data and make simple arithmetic mistakes. Fixing every flaw (including those often exhibited by humans) would involve building an artificial superintelligence, which is a whole other project.

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) means many different things to different people, but the most important parts of it have already been achieved by the current generation of advanced AI large language models such as ChatGPT, Bard, LLaMA and Claude. These “frontier models” have many flaws: They hallucinate scholarly citations and court cases, perpetuate biases from their training data and make simple arithmetic mistakes. Fixing every flaw (including those often exhibited by humans) would involve building an artificial superintelligence, which is a whole other project.

Nevertheless, today’s frontier models perform competently even on novel tasks they were not trained for, crossing a threshold that previous generations of AI and supervised deep learning systems never managed. Decades from now, they will be recognized as the first true examples of AGI, just as the 1945 ENIAC is now recognized as the first true general-purpose electronic computer.

more here.

The New York City Street That Changed American Art Forever

Jennifer Krasinski at Bookforum:

BETWEEN 1956 AND 1967, the Coenties Slip on the lower tip of Manhattan was home to a group of artists who had moved to the city with grand ambitions for their work and little money to their names. In those lean years, before they were canonized, Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, Lenore Tawney, Jack Youngerman, and Delphine Seyrig all took up residence in this “down downtown,” on a dead-end street on the East River where they nested themselves among fishing ships and sailors, the changing tides and unremitting grime, living at a remove from the New York City art world. Here on “the Slip”—a commercial dock designed for transience and exchange—they lived in cheap and drafty lofts, nurturing intuitions and ideas into radical practices, producing bodies of work that would, in the end, be very much a part of the zeitgeist.

BETWEEN 1956 AND 1967, the Coenties Slip on the lower tip of Manhattan was home to a group of artists who had moved to the city with grand ambitions for their work and little money to their names. In those lean years, before they were canonized, Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, Lenore Tawney, Jack Youngerman, and Delphine Seyrig all took up residence in this “down downtown,” on a dead-end street on the East River where they nested themselves among fishing ships and sailors, the changing tides and unremitting grime, living at a remove from the New York City art world. Here on “the Slip”—a commercial dock designed for transience and exchange—they lived in cheap and drafty lofts, nurturing intuitions and ideas into radical practices, producing bodies of work that would, in the end, be very much a part of the zeitgeist.

“Place is an undervalued determinant in creative output,” writes author-scholar Prudence Peiffer in The Slip: The New York City Street That Changed American Art, her tale of these artists at that time, proposing that any chronicle of an aesthetic evolution should consider not only who but also where.

more here.

How to Exclaim!

Florence Hazrat at The Millions:

Noisy. Hysterical. Brash. The textual version of junk food. The selfie of grammar. The exclamation point attracts enormous (and undue) amounts of flak for its unabashed claim to presence in the name of emotion which some unkind souls interpret as egotistical attention-seeking. We’ve grown suspicious of feelings, particularly the big ones needing the eruption of a ! to relieve ourselves. This trend started sometime around 1900 when modernity began to mean functionality and clean straight lines (witness the sensible boxes of a Bauhaus building), rather than the “extra” mood of Victorian sensitivity or frilly playful Renaissance decorations.

Noisy. Hysterical. Brash. The textual version of junk food. The selfie of grammar. The exclamation point attracts enormous (and undue) amounts of flak for its unabashed claim to presence in the name of emotion which some unkind souls interpret as egotistical attention-seeking. We’ve grown suspicious of feelings, particularly the big ones needing the eruption of a ! to relieve ourselves. This trend started sometime around 1900 when modernity began to mean functionality and clean straight lines (witness the sensible boxes of a Bauhaus building), rather than the “extra” mood of Victorian sensitivity or frilly playful Renaissance decorations.

Things need to make sense, and the ! just doesn’t, subjective and subversive as it is, popping out from the uniform flow of words on the line. Since the triumphal conquering of smartphone technology and social media, the exclamation point finds fewer and fewer friends: We live in a digital village, chatting to one another from across the globe, and will use emotive social cues such as the exclamation point, and plenty of them.

More here.