Karmela Padavic-Callaghan in Nature:

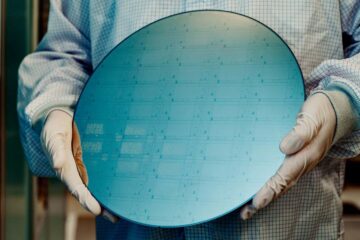

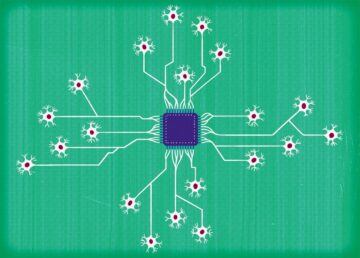

As a contender in the race to build an error-free quantum supercomputer, IBM has been taking a different tack than its most direct competitors. Now, the firm has unveiled two new quantum computers, called Nighthawk and Loon, that may validate its approach and could provide innovations needed to make the next generation of these devices truly useful.

As a contender in the race to build an error-free quantum supercomputer, IBM has been taking a different tack than its most direct competitors. Now, the firm has unveiled two new quantum computers, called Nighthawk and Loon, that may validate its approach and could provide innovations needed to make the next generation of these devices truly useful.

IBM’s quantum supercomputer design is modular and relies on developing new ways to connect superconducting qubits within and across different quantum computer units. When the firm first debuted it, some researchers questioned the practicality of these connections, says Jay Gambetta at IBM. He says it was as if people were saying to the IBM team: “‘You’re in theory land, you cannot realise that.’ And [now] we’re going to show that [to be] wrong.”

Within Loon, each qubit is connected to six others and those connections can “break the plane”, which means they don’t just travel across a chip but can move vertically as well, a capability that no other superconducting quantum computer has had so far.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

I came of age as a reader in the 1970s, when apocalyptic fiction was much in vogue because of intensifying nuclear anxieties. As a teenager, I devoured books set in the aftermath of an atomic catastrophe, like Nevil Shute’s On the Beach and John Wyndham’s The Chrysalids.

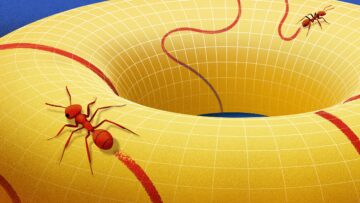

I came of age as a reader in the 1970s, when apocalyptic fiction was much in vogue because of intensifying nuclear anxieties. As a teenager, I devoured books set in the aftermath of an atomic catastrophe, like Nevil Shute’s On the Beach and John Wyndham’s The Chrysalids. You notice an ant struggling in a puddle of water. Their legs thrash as they fight to stay afloat. You could walk past, or you could take a moment to tip a leaf or a twig into the puddle, giving them a chance to climb out. The choice may feel trivial. And yet this small encounter, which resembles the ‘drowning child’ case from Peter Singer’s

You notice an ant struggling in a puddle of water. Their legs thrash as they fight to stay afloat. You could walk past, or you could take a moment to tip a leaf or a twig into the puddle, giving them a chance to climb out. The choice may feel trivial. And yet this small encounter, which resembles the ‘drowning child’ case from Peter Singer’s

Brain implants

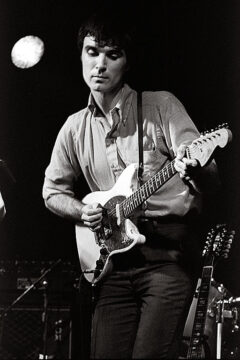

Brain implants If you spend enough time wandering around downtown Manhattan, the odds are that you’ll eventually encounter the musician David Byrne riding a bicycle. (He owns four: a folding bike, an electric, an eight-speed, and a single-speed, which he recently lent to the pop singer Lorde.) One day this past June, pedalling alongside Byrne from his apartment in Chelsea to the Governors Island ferry, I watched at least a dozen New Yorkers clock his profile, whipping around to squint, softly pinching the arm of their companion and whispering, “Was that . . . ?” By then, Byrne was gone, a tuft of white hair whizzing toward the horizon. Spotting Byrne on two wheels has become a New York City rite of passage, like sussing out the best halal cart in midtown, or dropping something important onto the subway tracks. During the few months that Byrne and I spent together, I never saw him traverse the city via any other mode of transportation, even when the heat index was approaching hellscape and he was overdue for a meeting in Brooklyn. He simply reapplied sunscreen and pushed off. In 2023, he rode a custom white Budnitz single-speed directly onto the red carpet at the Met Gala while wearing a cream-colored turtleneck under a bespoke white suit by Martin Greenfield Clothiers. (The bike featured a belt drive, which prevented chain grease from smearing his pants; he had placed his parking placard for the gala in the basket.) In 2019, Byrne rode a bicycle onstage at the “Tonight Show” while promoting “David Byrne’s American Utopia,” a Broadway production that he wrote and starred in that year. (In 2020, it became a film, directed by Spike Lee.)

If you spend enough time wandering around downtown Manhattan, the odds are that you’ll eventually encounter the musician David Byrne riding a bicycle. (He owns four: a folding bike, an electric, an eight-speed, and a single-speed, which he recently lent to the pop singer Lorde.) One day this past June, pedalling alongside Byrne from his apartment in Chelsea to the Governors Island ferry, I watched at least a dozen New Yorkers clock his profile, whipping around to squint, softly pinching the arm of their companion and whispering, “Was that . . . ?” By then, Byrne was gone, a tuft of white hair whizzing toward the horizon. Spotting Byrne on two wheels has become a New York City rite of passage, like sussing out the best halal cart in midtown, or dropping something important onto the subway tracks. During the few months that Byrne and I spent together, I never saw him traverse the city via any other mode of transportation, even when the heat index was approaching hellscape and he was overdue for a meeting in Brooklyn. He simply reapplied sunscreen and pushed off. In 2023, he rode a custom white Budnitz single-speed directly onto the red carpet at the Met Gala while wearing a cream-colored turtleneck under a bespoke white suit by Martin Greenfield Clothiers. (The bike featured a belt drive, which prevented chain grease from smearing his pants; he had placed his parking placard for the gala in the basket.) In 2019, Byrne rode a bicycle onstage at the “Tonight Show” while promoting “David Byrne’s American Utopia,” a Broadway production that he wrote and starred in that year. (In 2020, it became a film, directed by Spike Lee.) When I arrived in Harlem, I felt anguished responsibility and resentment toward the cat. He could die, I perseverated. I had imagined Manhattan from the vantage point of a twenty-something with her lover, but was now relegated to “indoor New York lesbian with dying cat.” I searched his litter for pee and poop, as though playing a weird Where’s Waldo? Tom needed anti-anxiety medication with his wet food, and I was careful with the timing and dosage. I bypassed New York City nightlife to keep the cat alive.

When I arrived in Harlem, I felt anguished responsibility and resentment toward the cat. He could die, I perseverated. I had imagined Manhattan from the vantage point of a twenty-something with her lover, but was now relegated to “indoor New York lesbian with dying cat.” I searched his litter for pee and poop, as though playing a weird Where’s Waldo? Tom needed anti-anxiety medication with his wet food, and I was careful with the timing and dosage. I bypassed New York City nightlife to keep the cat alive. Standing in the middle of a field, we can easily forget that we live on a round planet. We’re so small in comparison to the Earth that from our point of view, it looks flat.

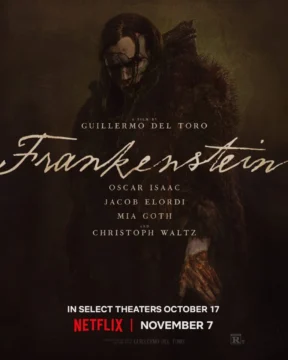

Standing in the middle of a field, we can easily forget that we live on a round planet. We’re so small in comparison to the Earth that from our point of view, it looks flat. GUILLERMO DEL TORO

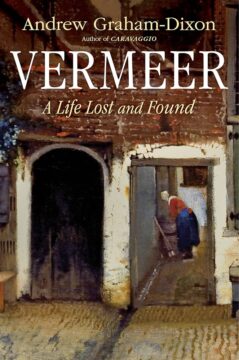

GUILLERMO DEL TORO From the sparse scatter of documents testifying to the life of Vermeer, many of them forbiddingly brief or boring or purely legal, Graham-Dixon constructs a compelling story. But it is a story – like those fictions which Vermeer’s paintings, with that mysterious charge of meaningfulness, have frequently inspired. Here, narrative drive is supplied by Vermeer’s supposed enmity with his mother-in-law, Maria Thins, a Catholic woman who, though she at first refused to condone her daughter’s marriage to a Protestant, thawed sufficiently to allow him and his family to live in her house. Facts which suggest Vermeer accommodated himself to the Catholic faith, an assumption which has informed much recent scholarship, are explained away as the triumphs of Maria. Two of the Vermeers’ many children were called Ignatius and Franciscus and another sent away to train for the priesthood – Graham-Dixon sees this as ‘a resounding victory’ for Maria’s ‘militant Catholicism’ over Vermeer’s Collegiant will. The accoutrements of a Catholic household chapel which appear in the inventory of his goods drawn up after his death were only acquired ‘through gritted teeth’. Early modern confessional hostilities are still being fought in the book’s prose: the Catholics ‘were all in it together’; Vermeer was ‘living in a nest of Jesuits’.

From the sparse scatter of documents testifying to the life of Vermeer, many of them forbiddingly brief or boring or purely legal, Graham-Dixon constructs a compelling story. But it is a story – like those fictions which Vermeer’s paintings, with that mysterious charge of meaningfulness, have frequently inspired. Here, narrative drive is supplied by Vermeer’s supposed enmity with his mother-in-law, Maria Thins, a Catholic woman who, though she at first refused to condone her daughter’s marriage to a Protestant, thawed sufficiently to allow him and his family to live in her house. Facts which suggest Vermeer accommodated himself to the Catholic faith, an assumption which has informed much recent scholarship, are explained away as the triumphs of Maria. Two of the Vermeers’ many children were called Ignatius and Franciscus and another sent away to train for the priesthood – Graham-Dixon sees this as ‘a resounding victory’ for Maria’s ‘militant Catholicism’ over Vermeer’s Collegiant will. The accoutrements of a Catholic household chapel which appear in the inventory of his goods drawn up after his death were only acquired ‘through gritted teeth’. Early modern confessional hostilities are still being fought in the book’s prose: the Catholics ‘were all in it together’; Vermeer was ‘living in a nest of Jesuits’. Twenty years ago, in November of 2005, Duke University Press published my first book: “

Twenty years ago, in November of 2005, Duke University Press published my first book: “ In a town on the shores of Lake Geneva sit clumps of living human brain cells for hire. These blobs, about the size of a grain of sand, can receive electrical signals and respond to them — much as computers do. Research teams from around the world can send the blobs tasks, in the hope that they will process the information and send a signal back.

In a town on the shores of Lake Geneva sit clumps of living human brain cells for hire. These blobs, about the size of a grain of sand, can receive electrical signals and respond to them — much as computers do. Research teams from around the world can send the blobs tasks, in the hope that they will process the information and send a signal back. Turning to philosophy to learn how to live is nothing new, of course. But the explicitly inspirational and instructional valence of much that appears today under that heading, even from academic presses, is striking — as is the apparent consensus that the central task of philosophy is to guide seekers to a greater acceptance of imperfection and insignificance. Sometimes these books focus on a particular school of philosophy, giving readers an “-ism” — existentialism, Buddhism, Taoism, and above all Stoicism, now practically a genre unto itself — with which to identify. Others staple together eclectic smatterings of received ideas into less partisan surveys on how to cope with failure and disillusionment.

Turning to philosophy to learn how to live is nothing new, of course. But the explicitly inspirational and instructional valence of much that appears today under that heading, even from academic presses, is striking — as is the apparent consensus that the central task of philosophy is to guide seekers to a greater acceptance of imperfection and insignificance. Sometimes these books focus on a particular school of philosophy, giving readers an “-ism” — existentialism, Buddhism, Taoism, and above all Stoicism, now practically a genre unto itself — with which to identify. Others staple together eclectic smatterings of received ideas into less partisan surveys on how to cope with failure and disillusionment.