Matt Lutz at Humean Being:

Within the broader discipline of philosophy, there is a split between what is called “analytic philosophy” and what is called “continental philosophy.” The gulf between these two camps is wide, and the dispute between them extremely acrimonious, although it is hard to articulate precisely what the difference between the two is. Any proposed account of this distinction – analytic philosophers are like this, while continentals are like that – will inevitably result in very angry objections. For one thing, any proposed distinction will inevitably mischaracterize several paradigmatic continental or analytic philosophers. But more importantly, the person proposing the distinction is usually a partisan of one camp or the other, and they characterize the distinction in terms that are extremely flattering to their own side. “Analytic philosophers prize rigor and clarity,” says that analytic philosopher, “whereas continentals do not.” “Go fuck yourself,” the continental philosopher replies.

Within the broader discipline of philosophy, there is a split between what is called “analytic philosophy” and what is called “continental philosophy.” The gulf between these two camps is wide, and the dispute between them extremely acrimonious, although it is hard to articulate precisely what the difference between the two is. Any proposed account of this distinction – analytic philosophers are like this, while continentals are like that – will inevitably result in very angry objections. For one thing, any proposed distinction will inevitably mischaracterize several paradigmatic continental or analytic philosophers. But more importantly, the person proposing the distinction is usually a partisan of one camp or the other, and they characterize the distinction in terms that are extremely flattering to their own side. “Analytic philosophers prize rigor and clarity,” says that analytic philosopher, “whereas continentals do not.” “Go fuck yourself,” the continental philosopher replies.

Despite the difficulty with giving a strict characterization, analytic philosophy and continental philosophy have very different vibes.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Rats have gotten a bad reputation over the years for being dirty,

Rats have gotten a bad reputation over the years for being dirty,

In 2004 the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben was scheduled to spend the spring semester as a visiting professor at NYU. On January 5 of that year, however, the Department of Homeland Security launched a new program to collect fingerprints from foreign visitors. Though EU citizens were exempted, three days later Agamben announced that “personally, I have no intention of submitting myself to such procedures,” and he refused to come to the US. In a statement first published in La Repubblica, he warned that collecting fingerprints marked a new “threshold in the control and manipulation of bodies”—what Michel Foucault had named “biopolitics.” Agamben described fingerprint collection as a perfect example of this tyranny over bodies and called it “biopolitical tattooing,” analogous to the tattooing of numbers on prisoners’ arms at Auschwitz.

In 2004 the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben was scheduled to spend the spring semester as a visiting professor at NYU. On January 5 of that year, however, the Department of Homeland Security launched a new program to collect fingerprints from foreign visitors. Though EU citizens were exempted, three days later Agamben announced that “personally, I have no intention of submitting myself to such procedures,” and he refused to come to the US. In a statement first published in La Repubblica, he warned that collecting fingerprints marked a new “threshold in the control and manipulation of bodies”—what Michel Foucault had named “biopolitics.” Agamben described fingerprint collection as a perfect example of this tyranny over bodies and called it “biopolitical tattooing,” analogous to the tattooing of numbers on prisoners’ arms at Auschwitz. When David Szalay’s novel “

When David Szalay’s novel “ Bees in hives produce hexagonal honeycomb. Why? According to the “honeycomb conjecture” in mathematics, hexagons are the most efficient shape for tiling the plane. If you want to fully cover a surface using tiles of a uniform shape and size while keeping the total length of the perimeter to a minimum, hexagons are the shape to use.

Bees in hives produce hexagonal honeycomb. Why? According to the “honeycomb conjecture” in mathematics, hexagons are the most efficient shape for tiling the plane. If you want to fully cover a surface using tiles of a uniform shape and size while keeping the total length of the perimeter to a minimum, hexagons are the shape to use.  István isn’t one of the most talkative characters in literary fiction. He says “yeah” and “okay” a lot, and is mostly reactive to the world around him. But that quietness covers up a tumultuous life — from Hungary to England, from poverty to being in close contact with the super-rich.

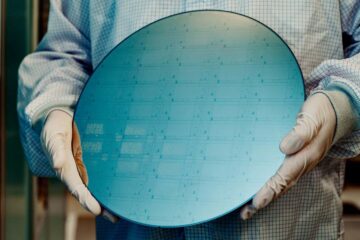

István isn’t one of the most talkative characters in literary fiction. He says “yeah” and “okay” a lot, and is mostly reactive to the world around him. But that quietness covers up a tumultuous life — from Hungary to England, from poverty to being in close contact with the super-rich. As a contender in the race to build an

As a contender in the race to build an  I came of age as a reader in the 1970s, when apocalyptic fiction was much in vogue because of intensifying nuclear anxieties. As a teenager, I devoured books set in the aftermath of an atomic catastrophe, like Nevil Shute’s On the Beach and John Wyndham’s The Chrysalids.

I came of age as a reader in the 1970s, when apocalyptic fiction was much in vogue because of intensifying nuclear anxieties. As a teenager, I devoured books set in the aftermath of an atomic catastrophe, like Nevil Shute’s On the Beach and John Wyndham’s The Chrysalids. You notice an ant struggling in a puddle of water. Their legs thrash as they fight to stay afloat. You could walk past, or you could take a moment to tip a leaf or a twig into the puddle, giving them a chance to climb out. The choice may feel trivial. And yet this small encounter, which resembles the ‘drowning child’ case from Peter Singer’s

You notice an ant struggling in a puddle of water. Their legs thrash as they fight to stay afloat. You could walk past, or you could take a moment to tip a leaf or a twig into the puddle, giving them a chance to climb out. The choice may feel trivial. And yet this small encounter, which resembles the ‘drowning child’ case from Peter Singer’s

Brain implants

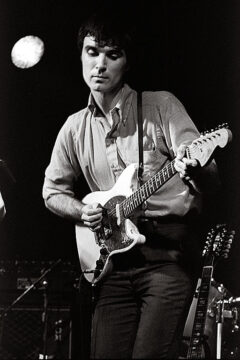

Brain implants If you spend enough time wandering around downtown Manhattan, the odds are that you’ll eventually encounter the musician David Byrne riding a bicycle. (He owns four: a folding bike, an electric, an eight-speed, and a single-speed, which he recently lent to the pop singer Lorde.) One day this past June, pedalling alongside Byrne from his apartment in Chelsea to the Governors Island ferry, I watched at least a dozen New Yorkers clock his profile, whipping around to squint, softly pinching the arm of their companion and whispering, “Was that . . . ?” By then, Byrne was gone, a tuft of white hair whizzing toward the horizon. Spotting Byrne on two wheels has become a New York City rite of passage, like sussing out the best halal cart in midtown, or dropping something important onto the subway tracks. During the few months that Byrne and I spent together, I never saw him traverse the city via any other mode of transportation, even when the heat index was approaching hellscape and he was overdue for a meeting in Brooklyn. He simply reapplied sunscreen and pushed off. In 2023, he rode a custom white Budnitz single-speed directly onto the red carpet at the Met Gala while wearing a cream-colored turtleneck under a bespoke white suit by Martin Greenfield Clothiers. (The bike featured a belt drive, which prevented chain grease from smearing his pants; he had placed his parking placard for the gala in the basket.) In 2019, Byrne rode a bicycle onstage at the “Tonight Show” while promoting “David Byrne’s American Utopia,” a Broadway production that he wrote and starred in that year. (In 2020, it became a film, directed by Spike Lee.)

If you spend enough time wandering around downtown Manhattan, the odds are that you’ll eventually encounter the musician David Byrne riding a bicycle. (He owns four: a folding bike, an electric, an eight-speed, and a single-speed, which he recently lent to the pop singer Lorde.) One day this past June, pedalling alongside Byrne from his apartment in Chelsea to the Governors Island ferry, I watched at least a dozen New Yorkers clock his profile, whipping around to squint, softly pinching the arm of their companion and whispering, “Was that . . . ?” By then, Byrne was gone, a tuft of white hair whizzing toward the horizon. Spotting Byrne on two wheels has become a New York City rite of passage, like sussing out the best halal cart in midtown, or dropping something important onto the subway tracks. During the few months that Byrne and I spent together, I never saw him traverse the city via any other mode of transportation, even when the heat index was approaching hellscape and he was overdue for a meeting in Brooklyn. He simply reapplied sunscreen and pushed off. In 2023, he rode a custom white Budnitz single-speed directly onto the red carpet at the Met Gala while wearing a cream-colored turtleneck under a bespoke white suit by Martin Greenfield Clothiers. (The bike featured a belt drive, which prevented chain grease from smearing his pants; he had placed his parking placard for the gala in the basket.) In 2019, Byrne rode a bicycle onstage at the “Tonight Show” while promoting “David Byrne’s American Utopia,” a Broadway production that he wrote and starred in that year. (In 2020, it became a film, directed by Spike Lee.)