Glorious World

I feel it again and again, no matter

Whether I am old or young:

A mountain range in the night,

On the balcony a silent woman,

A white street in the moonliglht curving gently away

That tears my heart with longing out of my body.

Oh burning world, oh white woman on the balcony,

Baying dog in the valley, train rolling far away,

What liars you were, how bitterly you deceived me,

Yet you turn out to be any sweetest dream and illusion.

Often I tried the frightening way of “reality,”

Where things that count are profession, law, fashion, finance.

But disillusioned and freed I fled away alone

To the other side, the place of dreams and blessed folly.

Sultry wind in the tree at night, dark gypsy woman,

World full of foolish yearning and the poet’s breath,

Glorious world I always come back to,

Where your heat lightning beckons me,

where your voice

calls!

by Hermann Hesse

from Poetic Outlaws

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Lehman the poet-journalist was now series editor of a popular anthology, a prestige role that bred more prestige roles: judging the National Book Award for poetry, editing The Oxford Anthology of American Poetry, and a 22-year position teaching creative writing at The New School. By handing over annual guest editorship of The Best American Poetry to prominent poets such as Ashbery, Yusef Komunyakaa, Edward Hirsch, and Louise Glück, Lehman aligned the anthology series with a broad spectrum of influential and prize-winning poets whose “ecumenical” taste—Lehman’s favored descriptor for his guest editors’ disposition—became aligned with his own.

Lehman the poet-journalist was now series editor of a popular anthology, a prestige role that bred more prestige roles: judging the National Book Award for poetry, editing The Oxford Anthology of American Poetry, and a 22-year position teaching creative writing at The New School. By handing over annual guest editorship of The Best American Poetry to prominent poets such as Ashbery, Yusef Komunyakaa, Edward Hirsch, and Louise Glück, Lehman aligned the anthology series with a broad spectrum of influential and prize-winning poets whose “ecumenical” taste—Lehman’s favored descriptor for his guest editors’ disposition—became aligned with his own.

I had a visceral distaste for the country’s imperial hegemony and its support of oppressive regimes all over the world in the name of fighting the Cold War. The ongoing Vietnam War was an obvious irritant. At the same time, I knew that in the world of new ideas, entrepreneurial innovations and academic excellence, American pre-eminence was undeniable.

I had a visceral distaste for the country’s imperial hegemony and its support of oppressive regimes all over the world in the name of fighting the Cold War. The ongoing Vietnam War was an obvious irritant. At the same time, I knew that in the world of new ideas, entrepreneurial innovations and academic excellence, American pre-eminence was undeniable. THE PATERNITY OF Hicks McTaggart—defender of dames, dodger of bombs, twirler of spaghetti, the amiable behemoth hero of Thomas Pynchon’s Shadow Ticket who prowls the streets of Depression-era Milwaukee—is a question his author leaves open. His mother, Grace, and her sister, Peony, “grew up in the Driftless Area, a patch of Wisconsin never visited by glaciers, so that its terrain tends to be a little less flat and ground down than the rest of the state, free of the rubble, known as drift, that glaciers leave behind.” (Despite its charming name, the Driftless Area is a real place, not a Pynchonian invention.) Once old enough to hitchhike (“Soon as they could figure out how to bring their thumbs out of their mouths and into the wind”), Grace and Peony started consorting with circus performers wintering in Baraboo, a town at the Driftless Area’s northeastern edge, before making their way to Milwaukee to take ordinary jobs and marry ordinary men. Grace’s marriage to Eddie McTaggart was interrupted by the discovery of her ongoing affair with Max, a German elephant trainer back in Baraboo. Eddie skipped town and headed west, never to be heard from again. Of Max we are told: “When other boys got sentimental they talked about all the children you were going to have, with Max it was more likely to be elephants.”

THE PATERNITY OF Hicks McTaggart—defender of dames, dodger of bombs, twirler of spaghetti, the amiable behemoth hero of Thomas Pynchon’s Shadow Ticket who prowls the streets of Depression-era Milwaukee—is a question his author leaves open. His mother, Grace, and her sister, Peony, “grew up in the Driftless Area, a patch of Wisconsin never visited by glaciers, so that its terrain tends to be a little less flat and ground down than the rest of the state, free of the rubble, known as drift, that glaciers leave behind.” (Despite its charming name, the Driftless Area is a real place, not a Pynchonian invention.) Once old enough to hitchhike (“Soon as they could figure out how to bring their thumbs out of their mouths and into the wind”), Grace and Peony started consorting with circus performers wintering in Baraboo, a town at the Driftless Area’s northeastern edge, before making their way to Milwaukee to take ordinary jobs and marry ordinary men. Grace’s marriage to Eddie McTaggart was interrupted by the discovery of her ongoing affair with Max, a German elephant trainer back in Baraboo. Eddie skipped town and headed west, never to be heard from again. Of Max we are told: “When other boys got sentimental they talked about all the children you were going to have, with Max it was more likely to be elephants.” T

T Despite the fact nearly no one knows her true identity, Elena Ferrante needs perhaps no introduction. The prolific and reclusive Italian writer has been writing since 1992, but reached international fame with My Brilliant Friend, the first of the Neapolitan Quartet of novels. It was the skillful hand of translator Ann Goldstein who helped introduce the novels to an English-reading audience. Though she was an integral part of one of the most popular works of fiction in the 21st century, Goldstein tells me she became a translator “accidentally,” after having studied Italian while working in the copy editing department of the New Yorker.

Despite the fact nearly no one knows her true identity, Elena Ferrante needs perhaps no introduction. The prolific and reclusive Italian writer has been writing since 1992, but reached international fame with My Brilliant Friend, the first of the Neapolitan Quartet of novels. It was the skillful hand of translator Ann Goldstein who helped introduce the novels to an English-reading audience. Though she was an integral part of one of the most popular works of fiction in the 21st century, Goldstein tells me she became a translator “accidentally,” after having studied Italian while working in the copy editing department of the New Yorker. Are AIs capable of murder?

Are AIs capable of murder? As Jeff Chang puts it in “Water Mirror Echo,” his exuberant new book about Lee as both a celebrity and an Asian American, the restless actor oscillated between “follow-the-flow Zen surrender” and “sunset-chasing American ambition.” Chang gets his title from a portion of a Taoist classic, “The Liezi,” that Lee found striking enough to transcribe:

As Jeff Chang puts it in “Water Mirror Echo,” his exuberant new book about Lee as both a celebrity and an Asian American, the restless actor oscillated between “follow-the-flow Zen surrender” and “sunset-chasing American ambition.” Chang gets his title from a portion of a Taoist classic, “The Liezi,” that Lee found striking enough to transcribe: AI systems’ mastery of language may or may not portend a future of superintelligent AI minds, but it already provides a proof of concept for a revolution in gene editing. And though such a revolution promises to unlock transformative medical advancements, it also brings longstanding bioethical dilemmas to the fore: Should people of means be able to hardwire physical or cognitive advantages into their genomes, or their children’s? Where is the line between medical therapy and dehumanizing enhancements?

AI systems’ mastery of language may or may not portend a future of superintelligent AI minds, but it already provides a proof of concept for a revolution in gene editing. And though such a revolution promises to unlock transformative medical advancements, it also brings longstanding bioethical dilemmas to the fore: Should people of means be able to hardwire physical or cognitive advantages into their genomes, or their children’s? Where is the line between medical therapy and dehumanizing enhancements? W

W A

A According to the philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, the 20th century’s form of life also began with the air. Sloterdijk puts the moment at 6 p.m. on April 22, 1915, near Ypres, when a German regiment under the command of Col. Max Peterson unleashed chlorine gas in warfare for the first time. Previously, violence in war had been directed at the human body; this attack targeted the “living organism’s immersion in a breathable milieu,” as Sloterdijk writes in “

According to the philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, the 20th century’s form of life also began with the air. Sloterdijk puts the moment at 6 p.m. on April 22, 1915, near Ypres, when a German regiment under the command of Col. Max Peterson unleashed chlorine gas in warfare for the first time. Previously, violence in war had been directed at the human body; this attack targeted the “living organism’s immersion in a breathable milieu,” as Sloterdijk writes in “ The drug discovery and development landscape is plagued by inefficiency, risk and astronomical cost. Clinical success rates languish below 10%, convoluted in- and out-licensing workflows erode precious patent life, and industry estimates suggest that biopharma companies write off some $15 billion every year on deprioritized candidates. At the same time, more than 90% of oncology drugs—and a significant proportion of all therapeutics—will lose patent exclusivity within the next five years, creating a looming innovation shortfall. Partex is here to bridge that gap. As the world’s largest artificial intelligence (AI)-driven drug-asset manager, Partex supercharges pipelines, resurrects shelved compounds and slashes development time to clinic—revolutionizing discovery and development at every step.

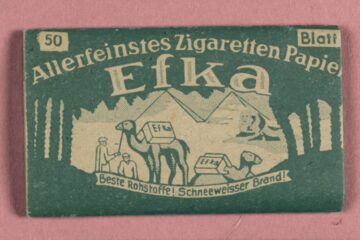

The drug discovery and development landscape is plagued by inefficiency, risk and astronomical cost. Clinical success rates languish below 10%, convoluted in- and out-licensing workflows erode precious patent life, and industry estimates suggest that biopharma companies write off some $15 billion every year on deprioritized candidates. At the same time, more than 90% of oncology drugs—and a significant proportion of all therapeutics—will lose patent exclusivity within the next five years, creating a looming innovation shortfall. Partex is here to bridge that gap. As the world’s largest artificial intelligence (AI)-driven drug-asset manager, Partex supercharges pipelines, resurrects shelved compounds and slashes development time to clinic—revolutionizing discovery and development at every step. Open one of the drawers in a collections cabinet at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and you’ll find a small booklet of Efka cigarette papers. The papers are part of a broader story the museum tells about Nazism, corporate collaboration, and wartime propaganda.

Open one of the drawers in a collections cabinet at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and you’ll find a small booklet of Efka cigarette papers. The papers are part of a broader story the museum tells about Nazism, corporate collaboration, and wartime propaganda.