Cassandra Neyenesch at Public Books:

Martha, a journalist played by Tilda Swinton, has terminal cancer. She asks her friend Ingrid (Julianne Moore) to come away with her to a house in upstate New York and be in the room next door when she takes a suicide pill she bought on the dark web. Like all of Pedro Almodóvar’s films, The Room Next Door is gorgeous to look at, completely unsentimental, and staunchly uninterested in absolutes, rules, or dogmas. This is Almodóvar’s gift: moral gray tones painted in vibrant colors. When Martha says the gangster line, “Cancer can’t get me if I get me first,” we sense that it’s an expression of Almodóvar’s own defiant punk spirit.

Martha, a journalist played by Tilda Swinton, has terminal cancer. She asks her friend Ingrid (Julianne Moore) to come away with her to a house in upstate New York and be in the room next door when she takes a suicide pill she bought on the dark web. Like all of Pedro Almodóvar’s films, The Room Next Door is gorgeous to look at, completely unsentimental, and staunchly uninterested in absolutes, rules, or dogmas. This is Almodóvar’s gift: moral gray tones painted in vibrant colors. When Martha says the gangster line, “Cancer can’t get me if I get me first,” we sense that it’s an expression of Almodóvar’s own defiant punk spirit.

Almodóvar is an artist of eros, in the sense that the dynamics between the characters tend to escalate into sex, not infrequently rape. The director is sex obsessed, but in earlier films like Talk to Her and Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! he also uses sex to provoke discomfort, disgust, and titillation in the viewer. It works because he himself is a siren, and he is seducing us. His movies are so ravishing and hilarious that we find ourselves helpless to patrol our boundaries, and we just give in to their transgressive spell.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Last week, OpenAI released a

Last week, OpenAI released a Five years ago, I wrote a commentary about the United Nations as it turned 75. The title, “

Five years ago, I wrote a commentary about the United Nations as it turned 75. The title, “ Cormac McCarthy, one of the greatest novelists America has ever produced and one of the most private, had been dead for 13 months when I arrived at his final residence outside Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was a stately old adobe house, two stories high with beam-ends jutting out of the exterior walls, set back from a country road in a valley below the mountains. First built in 1892, the house was expanded and modernized in the 1970s and extensively modified by McCarthy himself, who, it turns out, was a self-taught architect as well as a master of literary fiction.

Cormac McCarthy, one of the greatest novelists America has ever produced and one of the most private, had been dead for 13 months when I arrived at his final residence outside Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was a stately old adobe house, two stories high with beam-ends jutting out of the exterior walls, set back from a country road in a valley below the mountains. First built in 1892, the house was expanded and modernized in the 1970s and extensively modified by McCarthy himself, who, it turns out, was a self-taught architect as well as a master of literary fiction. C

C “Now he is scattered among a hundred cities,” W.H. Auden wrote in 1939, “And wholly given over to unfamiliar affections.” Auden was ruminating on the recent death of the Irish poet W.B. Yeats, but the words could serve as an epitaph for any great author. Poets like to imagine that their creations confer afterlives—for themselves and their subjects—impervious to the assaults of “wasteful war” and “sluttish time” so ruinous to monuments of marble or metal (see Horace’s Ode 3.30 and Shakespeare’s Sonnet 55). But as Auden recognized, the moment an author dies, his or her legacy is on the loose. Any chance those poems have of a future depends on what readers make of them: “The words of a dead man,” Auden continues, “Are modified in the guts of the living.”

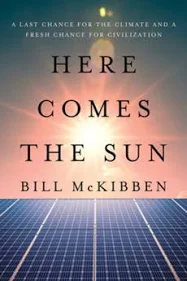

“Now he is scattered among a hundred cities,” W.H. Auden wrote in 1939, “And wholly given over to unfamiliar affections.” Auden was ruminating on the recent death of the Irish poet W.B. Yeats, but the words could serve as an epitaph for any great author. Poets like to imagine that their creations confer afterlives—for themselves and their subjects—impervious to the assaults of “wasteful war” and “sluttish time” so ruinous to monuments of marble or metal (see Horace’s Ode 3.30 and Shakespeare’s Sonnet 55). But as Auden recognized, the moment an author dies, his or her legacy is on the loose. Any chance those poems have of a future depends on what readers make of them: “The words of a dead man,” Auden continues, “Are modified in the guts of the living.” McKibben’s solar revolution has unfurled with startling rapidity. The last two years, he argues, have marked an epochal technoeconomic shift. And yet, despite a lot of solar deployment during that period, one would be hard-pressed to find much evidence of a shift in any of the key greenhouse-gas emissions metrics. The vast majority of global energy continues to be produced by fossil fuels, a fact that hasn’t much changed

McKibben’s solar revolution has unfurled with startling rapidity. The last two years, he argues, have marked an epochal technoeconomic shift. And yet, despite a lot of solar deployment during that period, one would be hard-pressed to find much evidence of a shift in any of the key greenhouse-gas emissions metrics. The vast majority of global energy continues to be produced by fossil fuels, a fact that hasn’t much changed  They say my generation is wasting our lives watching mindless entertainment. But I think things are worse than that. We are now turning our lives into mindless entertainment. Not just consuming slop, but becoming it.

They say my generation is wasting our lives watching mindless entertainment. But I think things are worse than that. We are now turning our lives into mindless entertainment. Not just consuming slop, but becoming it. ENERGY-RELATED CARBON EMISSIONS

ENERGY-RELATED CARBON EMISSIONS  While ants can be annoying (see: showing up at your picnic table), humans generally regard them as good workers, which is how they’ve often been portrayed in folklore and fables such as Aesop’s “

While ants can be annoying (see: showing up at your picnic table), humans generally regard them as good workers, which is how they’ve often been portrayed in folklore and fables such as Aesop’s “ Remember the last time you visited the doctor? They likely asked you about your medical history.

Remember the last time you visited the doctor? They likely asked you about your medical history. Here’s a very short, oversimplified history of modern economics. In the 1960s and 1970s, a particular way of thinking about economics crystallized in academic departments, and basically took over the top journals. It was very math-heavy, and it modeled the economy as the sum of a bunch of rational human agents buying and selling things in a market. Although the people who invented these methods (Paul Samuelson, Ken Arrow, etc.) were not very libertarian, in the 70s and 80s a bunch of conservative-leaning economists used the models to claim that free markets were great. The models turned out to be pretty useful for saying “free markets are great”, simply because math is hard — it’s a lot easier to mathematically model a simple, well-functioning market than it is to model a complex world where markets are only part of the story, and where markets themselves have lots of pieces that break down and don’t work.

Here’s a very short, oversimplified history of modern economics. In the 1960s and 1970s, a particular way of thinking about economics crystallized in academic departments, and basically took over the top journals. It was very math-heavy, and it modeled the economy as the sum of a bunch of rational human agents buying and selling things in a market. Although the people who invented these methods (Paul Samuelson, Ken Arrow, etc.) were not very libertarian, in the 70s and 80s a bunch of conservative-leaning economists used the models to claim that free markets were great. The models turned out to be pretty useful for saying “free markets are great”, simply because math is hard — it’s a lot easier to mathematically model a simple, well-functioning market than it is to model a complex world where markets are only part of the story, and where markets themselves have lots of pieces that break down and don’t work. Before moving to the United States at ten, I grew up surrounded by other Iranians. Aunts, uncles, cousins, and family friends who spoke my language and understood the nuances of my life. Then, in the suburbs of America, I suddenly understood isolation and loneliness. I was the new, dark kid from the country who took Americans hostage, the kid whose name, tastes and mannerisms were easy to mock, who didn’t know the rules to American sports or culture. My refuge from alienation came through stories. I came home from school every day and buried myself in fiction because it felt like the real world had no space for me. But the irony is that the fictional worlds I was most obsessed with had no place for me either.

Before moving to the United States at ten, I grew up surrounded by other Iranians. Aunts, uncles, cousins, and family friends who spoke my language and understood the nuances of my life. Then, in the suburbs of America, I suddenly understood isolation and loneliness. I was the new, dark kid from the country who took Americans hostage, the kid whose name, tastes and mannerisms were easy to mock, who didn’t know the rules to American sports or culture. My refuge from alienation came through stories. I came home from school every day and buried myself in fiction because it felt like the real world had no space for me. But the irony is that the fictional worlds I was most obsessed with had no place for me either. Senator Josh Hawley is

Senator Josh Hawley is