Heidi Ledford in Nature:

Off a quiet hallway on the top floor of a building at the University of Osaka in Japan, Katsuhiko Hayashi is hatching a revolution. He is on a decades-long quest to grow eggs and sperm in the laboratory. Hayashi wants to understand the fundamental biology of these reproductive cells. But, if he succeeds, it could forever alter how humans reproduce. Even for a scientist known for extreme doggedness, it has been a tortuous road. It has taken Hayashi to some strange places: his lab grows fragments of faux ovaries and testes in dishes and has produced mice with two fathers and no mother1. Every paper he publishes brings e-mails from people clamouring for help with their fertility. “I tell them, ‘This is still experimental’,” Hayashi says. “But sometimes, I can’t respond. There are too many.”

Off a quiet hallway on the top floor of a building at the University of Osaka in Japan, Katsuhiko Hayashi is hatching a revolution. He is on a decades-long quest to grow eggs and sperm in the laboratory. Hayashi wants to understand the fundamental biology of these reproductive cells. But, if he succeeds, it could forever alter how humans reproduce. Even for a scientist known for extreme doggedness, it has been a tortuous road. It has taken Hayashi to some strange places: his lab grows fragments of faux ovaries and testes in dishes and has produced mice with two fathers and no mother1. Every paper he publishes brings e-mails from people clamouring for help with their fertility. “I tell them, ‘This is still experimental’,” Hayashi says. “But sometimes, I can’t respond. There are too many.”

The work that Hayashi and others in the field are doing could offer fresh hope to people struggling with infertility, and to same-sex couples who want children who are genetically related to both partners. But despite the dazzling results researchers have achieved in rodents, that future remains distant. “The technology is super cool,” says Christian Kramme, chief scientific officer at Gameto, a fertility-focused biotechnology company in Austin, Texas. “But fundamentally, I don’t believe there is a single person in the world that should attempt to enact this clinically in the next decade.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

On a visit to the

On a visit to the  Surging temperatures worldwide have pushed

Surging temperatures worldwide have pushed  Well, it’s time for my annual Economics Nobel post! If you like, you can also check out my posts for

Well, it’s time for my annual Economics Nobel post! If you like, you can also check out my posts for  The exact moment when Earth will reach its tipping points—moments at which human-induced climate change will trigger irreversible planetary changes—has long been a

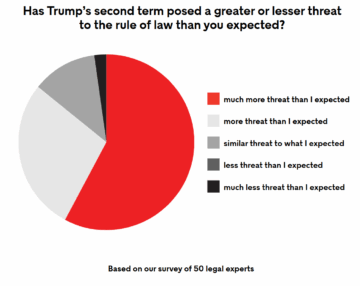

The exact moment when Earth will reach its tipping points—moments at which human-induced climate change will trigger irreversible planetary changes—has long been a  Last year, in the months before the 2024 presidential election,

Last year, in the months before the 2024 presidential election,  On April 28, 2025, at 12:33:24 CET, a blackout encompassed Spain, Portugal, and parts of southwest France, leaving over 50 million people without power. The loss of electricity cost Spain an estimated $1.82 billion in economic output and damages. When the Iberian grid collapsed, people who were going about their day moments before were now

On April 28, 2025, at 12:33:24 CET, a blackout encompassed Spain, Portugal, and parts of southwest France, leaving over 50 million people without power. The loss of electricity cost Spain an estimated $1.82 billion in economic output and damages. When the Iberian grid collapsed, people who were going about their day moments before were now

Despite their usefulness, large language models still have a reliability problem. A new study shows that

Despite their usefulness, large language models still have a reliability problem. A new study shows that  The mission with cancer therapy is clear: eradicate as many tumour cells as possible. Traditional chemotherapy remains a mainstay, where patients are dosed with potent compounds that disrupt essential cellular functions, preventing tumour cells from proliferating and ultimately forcing them to self-destruct. However, new findings

The mission with cancer therapy is clear: eradicate as many tumour cells as possible. Traditional chemotherapy remains a mainstay, where patients are dosed with potent compounds that disrupt essential cellular functions, preventing tumour cells from proliferating and ultimately forcing them to self-destruct. However, new findings The clues that Nicole Kidman and Keith Urban’s nearly 20-year marriage was cracking up were everywhere, according to an internet full of sleuths.

The clues that Nicole Kidman and Keith Urban’s nearly 20-year marriage was cracking up were everywhere, according to an internet full of sleuths.