Paul Glynn in BBC:

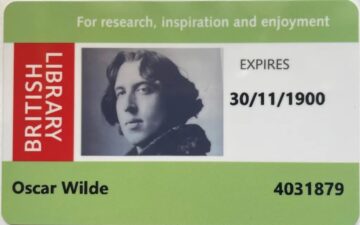

The British Library has honoured late Irish writer Oscar Wilde by reissuing a reader’s card in his name, 130 years after his original was revoked following his conviction for “gross indecency”.

The British Library has honoured late Irish writer Oscar Wilde by reissuing a reader’s card in his name, 130 years after his original was revoked following his conviction for “gross indecency”.

The celebrated novelist, poet and playwright was excluded from the library’s reading room in 1895 over his charge for having had homosexual relationships, which was a criminal offence at the time.

The new card, which will be collected by his grandson, author Merlin Holland, on Thursday, is intended to “acknowledge the injustices and immense suffering” Wilde faced, the library said.

Mr Holland said the new card is a “lovely gesture of forgiveness and I’m sure his spirit will be touched and delighted”.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The first time I read Yambo Ouologuem’s novel, Bound to Violence, I was shocked by the fury and seeming lack of restraint with which he wrote the story. Yet at the same time, his inventive style struck a chord with me, although I could not immediately explain why. I discovered the novel by chance at an antiquarian bookshop in Eindhoven, where I was living after my arrival in the Netherlands as a refugee fleeing the First Gulf War in Kuwait. The novel was tucked among books that had nothing to do with Africa, lined up alphabetically in a row as could be expected in bookstores or libraries. It was at that antiquarian bookshop that I encountered this book written by a man with a name that sounded Nigerian at first. The cover of the English translation was eye-catching: it was black with an image of a carved wooden mask impaled by a spear. The subtitle was noteworthy and revealing: A savage, panoramic novel of Black Africa.

The first time I read Yambo Ouologuem’s novel, Bound to Violence, I was shocked by the fury and seeming lack of restraint with which he wrote the story. Yet at the same time, his inventive style struck a chord with me, although I could not immediately explain why. I discovered the novel by chance at an antiquarian bookshop in Eindhoven, where I was living after my arrival in the Netherlands as a refugee fleeing the First Gulf War in Kuwait. The novel was tucked among books that had nothing to do with Africa, lined up alphabetically in a row as could be expected in bookstores or libraries. It was at that antiquarian bookshop that I encountered this book written by a man with a name that sounded Nigerian at first. The cover of the English translation was eye-catching: it was black with an image of a carved wooden mask impaled by a spear. The subtitle was noteworthy and revealing: A savage, panoramic novel of Black Africa. The project of understanding how the brain creates thoughts and feelings has progressed in fits and starts, leading some to despair that the so-called “mind-body” problem is fundamentally unanswerable. How can nonphysical ideas reside in physical brains? Yet, George Lakoff and Srini Narayanan claim in their new book The Neural Mind: How Brains Think, we now have a working theory.

The project of understanding how the brain creates thoughts and feelings has progressed in fits and starts, leading some to despair that the so-called “mind-body” problem is fundamentally unanswerable. How can nonphysical ideas reside in physical brains? Yet, George Lakoff and Srini Narayanan claim in their new book The Neural Mind: How Brains Think, we now have a working theory. Y

Y On the shelves and tables of any bookstore, be it Barnes & Noble or your neighborhood shop, you’ll find the latest fiction and non-fiction beckoning to be browsed. Browse you will, and maybe you’ll find an interesting book, but what you will rarely find in the majority of bookstores is a book published by an independent press. Indie publishing is blossoming these days as commercial publishers eschew wonderful books—essay collections and novels, memoirs, novellas, poetry, anthologies, flash fiction, short fiction, you name it—because these books are a little, or perhaps a lot, off the beaten path of mainstream American taste. That commercial publishers are in it for the money is understandable, and they do publish many excellent books, but independent publishers are usually in it for the books. For indie publishers whether a book will make a big profit (they hardly ever do) isn’t a consideration; indie presses publish books they love. Support for this labor comes from donations, grants, and private funds, while editors and staff sometimes work for little or no money. There is a vast world of indie books to be discovered and enjoyed, and while the readers of this journal and other literary journals like it may be doing just that, almost everyone else is not.

On the shelves and tables of any bookstore, be it Barnes & Noble or your neighborhood shop, you’ll find the latest fiction and non-fiction beckoning to be browsed. Browse you will, and maybe you’ll find an interesting book, but what you will rarely find in the majority of bookstores is a book published by an independent press. Indie publishing is blossoming these days as commercial publishers eschew wonderful books—essay collections and novels, memoirs, novellas, poetry, anthologies, flash fiction, short fiction, you name it—because these books are a little, or perhaps a lot, off the beaten path of mainstream American taste. That commercial publishers are in it for the money is understandable, and they do publish many excellent books, but independent publishers are usually in it for the books. For indie publishers whether a book will make a big profit (they hardly ever do) isn’t a consideration; indie presses publish books they love. Support for this labor comes from donations, grants, and private funds, while editors and staff sometimes work for little or no money. There is a vast world of indie books to be discovered and enjoyed, and while the readers of this journal and other literary journals like it may be doing just that, almost everyone else is not. Last year, the Republican Party relied heavily on Turning Point USA founder Charlie Kirk’s organizing prowess and influence among young voters to cement a second term for President Donald Trump, making significant gains in the 18–29-year-old vote, according to Pew Research analysis. Narrowing that gap and making other gains on President Joe Biden’s 2020 margins, Trump swept back into the White House. Kirk’s movement and role in narrowing the young voter gap from 30 points in 2016 to just 19 in 2024 has sparked debate over whether the GOP has cemented more broad appeal among young voters, a bloc that has typically been heavily Democratic.

Last year, the Republican Party relied heavily on Turning Point USA founder Charlie Kirk’s organizing prowess and influence among young voters to cement a second term for President Donald Trump, making significant gains in the 18–29-year-old vote, according to Pew Research analysis. Narrowing that gap and making other gains on President Joe Biden’s 2020 margins, Trump swept back into the White House. Kirk’s movement and role in narrowing the young voter gap from 30 points in 2016 to just 19 in 2024 has sparked debate over whether the GOP has cemented more broad appeal among young voters, a bloc that has typically been heavily Democratic. Bringing all Heaney’s poems together in one volume, this collection lets us see for the first time all the archaeological layers that make up his oeuvre, from the talismanic Death of a Naturalist (1966) to the visionary long poem Station Island (1984), on to the parables of The Haw Lantern (1987) and the intimacies of The Human Chain (2010), the last volume published during the poet’s lifetime. A key poem in that collection, Chanson d’Aventure, describes his journey to hospital in an ambulance following a stroke: “Strapped on, wheeled out, forklifted, locked / In position for the drive”. The book also makes available at last Heaney’s prose poems, Stations (1975), released in a small press edition by Ulsterman Publications, which Heaney effectively kept under wraps as he felt the publication of Geoffrey Hill’s Mercian Hymns – “a work of complete authority” – had stolen his thunder in this form.

Bringing all Heaney’s poems together in one volume, this collection lets us see for the first time all the archaeological layers that make up his oeuvre, from the talismanic Death of a Naturalist (1966) to the visionary long poem Station Island (1984), on to the parables of The Haw Lantern (1987) and the intimacies of The Human Chain (2010), the last volume published during the poet’s lifetime. A key poem in that collection, Chanson d’Aventure, describes his journey to hospital in an ambulance following a stroke: “Strapped on, wheeled out, forklifted, locked / In position for the drive”. The book also makes available at last Heaney’s prose poems, Stations (1975), released in a small press edition by Ulsterman Publications, which Heaney effectively kept under wraps as he felt the publication of Geoffrey Hill’s Mercian Hymns – “a work of complete authority” – had stolen his thunder in this form. I remember being a child and after the lights turned out I would look around my bedroom and I would see shapes in the darkness and I would become afraid – afraid these shapes were creatures I did not understand that wanted to do me harm. And so I’d turn my light on. And when I turned the light on I would be relieved because the creatures turned out to be a pile of clothes on a chair, or a bookshelf, or a lampshade.

I remember being a child and after the lights turned out I would look around my bedroom and I would see shapes in the darkness and I would become afraid – afraid these shapes were creatures I did not understand that wanted to do me harm. And so I’d turn my light on. And when I turned the light on I would be relieved because the creatures turned out to be a pile of clothes on a chair, or a bookshelf, or a lampshade. Book Abstract: Capitalism seems unstoppable. Laws and regulations that are meant to contain its excesses can slow its expansion but are unable to contain it. How is it that a system that relies extensively on the law to code assets as capital is so resistant to legal constraints is the big question this book addresses. The answer lies in the fact that capitalist law is Janus-faced: Its private law side empowers non-state actors to use law as a tool to build private wealth and power over others; the public law side seeks to rein in some actions, but it also protects private actors against state interference through constitutional constraints on state power. This is how private actors rule over others with impunity, shift the risk of their actions on society at large and the environment. I conclude that private law needs a reset to ground it in principles of mutual respect and support among private actors rather than exploitation and power.

Book Abstract: Capitalism seems unstoppable. Laws and regulations that are meant to contain its excesses can slow its expansion but are unable to contain it. How is it that a system that relies extensively on the law to code assets as capital is so resistant to legal constraints is the big question this book addresses. The answer lies in the fact that capitalist law is Janus-faced: Its private law side empowers non-state actors to use law as a tool to build private wealth and power over others; the public law side seeks to rein in some actions, but it also protects private actors against state interference through constitutional constraints on state power. This is how private actors rule over others with impunity, shift the risk of their actions on society at large and the environment. I conclude that private law needs a reset to ground it in principles of mutual respect and support among private actors rather than exploitation and power. On 25 November 1915, the American newspaper The Review published the extraordinary case of an 11-year-old boy with prodigious mathematical abilities. Perched on a hill close to a set of railroad tracks, he could memorise all the numbers of the train carriages that sped by at

On 25 November 1915, the American newspaper The Review published the extraordinary case of an 11-year-old boy with prodigious mathematical abilities. Perched on a hill close to a set of railroad tracks, he could memorise all the numbers of the train carriages that sped by at  Off a quiet hallway on the top floor of a building at the University of Osaka in Japan, Katsuhiko Hayashi is

Off a quiet hallway on the top floor of a building at the University of Osaka in Japan, Katsuhiko Hayashi is