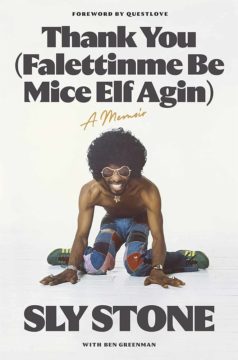

Alan Light at the New York Times:

One thing that remains intact for Stone at age 80 is the sense of wordplay and fun-house language that distinguished his lyrics (read the song/book title out loud), and some of the biggest pleasures in “Thank You” come when we witness him teasing out a theme. His response to other people telling his story and analyzing his struggles: “They’re trying to set the record straight. But a record’s not straight, especially when you’re not. It’s a circle with a spiral inside it. Every time a story is told it’s a test of memory and motive. … It isn’t evil but it isn’t good. It’s the name of the game but a shame just the same.”

One thing that remains intact for Stone at age 80 is the sense of wordplay and fun-house language that distinguished his lyrics (read the song/book title out loud), and some of the biggest pleasures in “Thank You” come when we witness him teasing out a theme. His response to other people telling his story and analyzing his struggles: “They’re trying to set the record straight. But a record’s not straight, especially when you’re not. It’s a circle with a spiral inside it. Every time a story is told it’s a test of memory and motive. … It isn’t evil but it isn’t good. It’s the name of the game but a shame just the same.”

Sylvester Stewart was born into a musical family (“There were seven of us, and the eighth member of the family was music”), and he started singing and recording with his siblings at a young age, soon joining a series of high school and regional bands.

more here.

Spanning from 625 BCE to 476 CE, the Roman Empire is still one of the most iconic of all time. At their highest, the Romans conquered Britain, Italy, much of the Middle East, the North African coast, Greece, Spain, and, of course, Italy. From their inventions to their way of life, Ancient Rome was one of the most influential cultures the planet has ever seen. Being the first city to have over 1 million people is just one of the things the time period has to its name, leading many to wonder what life in Rome was really like.

Spanning from 625 BCE to 476 CE, the Roman Empire is still one of the most iconic of all time. At their highest, the Romans conquered Britain, Italy, much of the Middle East, the North African coast, Greece, Spain, and, of course, Italy. From their inventions to their way of life, Ancient Rome was one of the most influential cultures the planet has ever seen. Being the first city to have over 1 million people is just one of the things the time period has to its name, leading many to wonder what life in Rome was really like. The first common argument for group minds is the argument from equivalence. I.e., a neuron is a very efficient and elegant way to transmit information. But one can transmit information with all sorts of things. There’s nothing supernatural about neurons. So could not an individual ant act much like a single neuron in an ant colony? And if you find it impossible to believe that an ant colony might be conscious, that it couldn’t emerge from pheromone trails and the collective little internal decisions of ants—if you find the idea of a conscious smell ridiculous—you have to then imagine opening up a human’s head and zooming in to neurons firing their action potentials, and explain why the same skepticism wouldn’t apply to our little cells that just puff vesicles filled with molecules at each other.

The first common argument for group minds is the argument from equivalence. I.e., a neuron is a very efficient and elegant way to transmit information. But one can transmit information with all sorts of things. There’s nothing supernatural about neurons. So could not an individual ant act much like a single neuron in an ant colony? And if you find it impossible to believe that an ant colony might be conscious, that it couldn’t emerge from pheromone trails and the collective little internal decisions of ants—if you find the idea of a conscious smell ridiculous—you have to then imagine opening up a human’s head and zooming in to neurons firing their action potentials, and explain why the same skepticism wouldn’t apply to our little cells that just puff vesicles filled with molecules at each other. Who knows how many times I stood before Carracci’s Venus, Adonis and Cupid without noticing a crucial detail, a tiny mark that holds as in a cipher the meaning of the tale. Perhaps I had not looked as closely as I thought. “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.” George Orwell’s remark about our observation of reality can be applied as well to works of art. Until recently, I had never noticed the speck of a red dot on Venus’ golden, shining skin, just on the edge of the small patch of shadow between her breasts, as if a pinprick had left behind a tiny trace of blood. I failed to see it even though the figure of Cupid was pointing from within the painting to where I should look. The picture itself discloses the key to decoding its riddle.

Who knows how many times I stood before Carracci’s Venus, Adonis and Cupid without noticing a crucial detail, a tiny mark that holds as in a cipher the meaning of the tale. Perhaps I had not looked as closely as I thought. “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.” George Orwell’s remark about our observation of reality can be applied as well to works of art. Until recently, I had never noticed the speck of a red dot on Venus’ golden, shining skin, just on the edge of the small patch of shadow between her breasts, as if a pinprick had left behind a tiny trace of blood. I failed to see it even though the figure of Cupid was pointing from within the painting to where I should look. The picture itself discloses the key to decoding its riddle. When I was in graduate school, I couldn’t make it through most of the talks presented in my department. I got bored and frustrated and tuned out. It was before smartphones, so I would doodle or fall asleep.

When I was in graduate school, I couldn’t make it through most of the talks presented in my department. I got bored and frustrated and tuned out. It was before smartphones, so I would doodle or fall asleep. Last week, we

Last week, we  This month marks an instructive centenary. On the morning of November 9, 1923, a 34-year-old Adolf Hitler led a column of 2,000 armed men through central Munich. The goal was to seize power by force in the Bavarian capital before marching on to Berlin. There, they would destroy the Weimar Republic – the democratic political system that had been established in Germany during the winter of 1918-19 – and replace it with an authoritarian regime committed to violence.

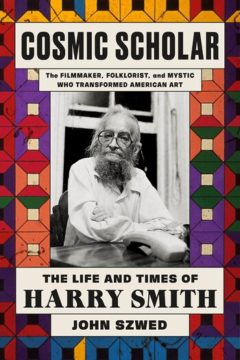

This month marks an instructive centenary. On the morning of November 9, 1923, a 34-year-old Adolf Hitler led a column of 2,000 armed men through central Munich. The goal was to seize power by force in the Bavarian capital before marching on to Berlin. There, they would destroy the Weimar Republic – the democratic political system that had been established in Germany during the winter of 1918-19 – and replace it with an authoritarian regime committed to violence. Smith was a loud ghost running wires between worlds, a “gnomish” saint who made connections more often than he made stuff. Hostile to the existence of galleries and museums and other obstacles to free circulation, Smith spent his life feeling for a pattern that might connect all the holy detritus in his ark: crushed Coke cans, paper airplanes, Seminole quilts, Ukrainian eggs, books, records, dead birds, string figures. The movies he painstakingly built from Vaseline and dye and paper cutouts changed how filmmakers saw the material of film itself. The problem for the historian is that Smith excelled in eliminating his own “excreta” (his word), throwing films under buses and tossing projectors out of windows. His close friend during the “Berkeley Renaissance” of 1948, the artist Jordan Belson, said that Smith “had nothing but insults and sarcasm for most art and most artists.” (This quote comes from the fantastic American Magus, a collection of interviews with those in Smith’s close circle first published in 1996, and one of Szwed’s sources.)

Smith was a loud ghost running wires between worlds, a “gnomish” saint who made connections more often than he made stuff. Hostile to the existence of galleries and museums and other obstacles to free circulation, Smith spent his life feeling for a pattern that might connect all the holy detritus in his ark: crushed Coke cans, paper airplanes, Seminole quilts, Ukrainian eggs, books, records, dead birds, string figures. The movies he painstakingly built from Vaseline and dye and paper cutouts changed how filmmakers saw the material of film itself. The problem for the historian is that Smith excelled in eliminating his own “excreta” (his word), throwing films under buses and tossing projectors out of windows. His close friend during the “Berkeley Renaissance” of 1948, the artist Jordan Belson, said that Smith “had nothing but insults and sarcasm for most art and most artists.” (This quote comes from the fantastic American Magus, a collection of interviews with those in Smith’s close circle first published in 1996, and one of Szwed’s sources.) Hals was not the second- or third-best Dutch painter of the seventeenth century; he was the best of the nineteenth. In the eighteen-sixties, the French art critic Théophile Thoré (who famously rescued Vermeer from oblivion) kicked off a revival of Hals, making him a favorite of art collectors and painters—Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet, Mary Cassatt and James McNeill Whistler, Robert Henri and George Luks. (Luks reportedly said that the only two great painters in history were Hals and himself.) By 1900, the city of Haarlem had installed a statue of Hals in a public park. Even as he fell behind Rembrandt and Vermeer in the twentieth century, his paintings would retain a sheen of newness. According to the painter Lucian Freud, Hals was “fated always to look modern.”

Hals was not the second- or third-best Dutch painter of the seventeenth century; he was the best of the nineteenth. In the eighteen-sixties, the French art critic Théophile Thoré (who famously rescued Vermeer from oblivion) kicked off a revival of Hals, making him a favorite of art collectors and painters—Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet, Mary Cassatt and James McNeill Whistler, Robert Henri and George Luks. (Luks reportedly said that the only two great painters in history were Hals and himself.) By 1900, the city of Haarlem had installed a statue of Hals in a public park. Even as he fell behind Rembrandt and Vermeer in the twentieth century, his paintings would retain a sheen of newness. According to the painter Lucian Freud, Hals was “fated always to look modern.” Jacob Elordi is by far the bigger name among the two stars of

Jacob Elordi is by far the bigger name among the two stars of Most people who have pulled an all-nighter are all too familiar with that “tired and wired” feeling. Although the body is physically exhausted, the brain feels slap-happy, loopy and almost giddy. Now, Northwestern University neurobiologists are the first to uncover what produces this punch-drunk effect. In a new study, researchers induced mild, acute sleep deprivation in mice and then examined their behaviors and

Most people who have pulled an all-nighter are all too familiar with that “tired and wired” feeling. Although the body is physically exhausted, the brain feels slap-happy, loopy and almost giddy. Now, Northwestern University neurobiologists are the first to uncover what produces this punch-drunk effect. In a new study, researchers induced mild, acute sleep deprivation in mice and then examined their behaviors and  The night I saw Killers of the Flower Moon I dreamed wildly, fitfully. Until I went to bed, I spent my waking hours thinking about the film, and then I suppose I continued to think about it as I slept. I have many questions about it. There are so many details I’d like to discuss. I wish I had seen it with friends, rather than (as is customary for my job) by myself with only my notebook to aid in exegesis. Killers of the Flower Moon, which was directed by Martin Scorsese, screen-written by Scorsese and Eric Roth, and based on the monumental nonfiction book of the same name by David Grann, is a tremendous feat of filmmaking, but it’s not a simple one, not an easy one.

The night I saw Killers of the Flower Moon I dreamed wildly, fitfully. Until I went to bed, I spent my waking hours thinking about the film, and then I suppose I continued to think about it as I slept. I have many questions about it. There are so many details I’d like to discuss. I wish I had seen it with friends, rather than (as is customary for my job) by myself with only my notebook to aid in exegesis. Killers of the Flower Moon, which was directed by Martin Scorsese, screen-written by Scorsese and Eric Roth, and based on the monumental nonfiction book of the same name by David Grann, is a tremendous feat of filmmaking, but it’s not a simple one, not an easy one. In 1978, the painter Nicky Nodjoumi returned to Tehran from New York just in time for the women’s mass marches against the shah. While there, Nodjoumi joined 30 students and professors in the production of posters at Tehran University’s Faculty of Fine Arts. The group held an exhibition to which some 5,000 people a day came, and a space for people to make their own posters. This particular effort of nonsectarian democracy in action—working with but keeping independent of all parties and factions—was short-lived. The art spaces were burned down by a hardline Muslim organization in 1979.

In 1978, the painter Nicky Nodjoumi returned to Tehran from New York just in time for the women’s mass marches against the shah. While there, Nodjoumi joined 30 students and professors in the production of posters at Tehran University’s Faculty of Fine Arts. The group held an exhibition to which some 5,000 people a day came, and a space for people to make their own posters. This particular effort of nonsectarian democracy in action—working with but keeping independent of all parties and factions—was short-lived. The art spaces were burned down by a hardline Muslim organization in 1979.