Toril Moi at The Point:

One evening in 1932, Simone de Beauvoir joined Jean-Paul Sartre and his old schoolfriend, the philosopher Raymond Aron, for a drink at a bar in Montparnasse. The three of them enthusiastically ordered apricot cocktails, the specialty of the house. Aron, who had just returned to Paris from a year studying philosophy in Berlin, suddenly pointed to his glass and said: “If you are a phenomenologist, you can talk about this cocktail and make philosophy out of it!” According to Beauvoir, Sartre “turned pale with emotion.” This was exactly what he wanted to do: “describe objects just as he saw and touched them, and to make philosophy out of it.”

One evening in 1932, Simone de Beauvoir joined Jean-Paul Sartre and his old schoolfriend, the philosopher Raymond Aron, for a drink at a bar in Montparnasse. The three of them enthusiastically ordered apricot cocktails, the specialty of the house. Aron, who had just returned to Paris from a year studying philosophy in Berlin, suddenly pointed to his glass and said: “If you are a phenomenologist, you can talk about this cocktail and make philosophy out of it!” According to Beauvoir, Sartre “turned pale with emotion.” This was exactly what he wanted to do: “describe objects just as he saw and touched them, and to make philosophy out of it.”

Phenomenology—the tradition of philosophy after Husserl and Heidegger—sets aside questions of essence and ontology and tries instead to grasp phenomena as a particular subject experiences them. A philosophy concerned with perception and experience would allow Sartre to shrink the gap between literature and philosophy and write philosophical texts filled with scintillating, though sometimes sexist, descriptions, anecdotes and stories: a cafe waiter playing at being a waiter, a woman who has gone to a cafe for a first date, a man flooded with shame when he is caught peeping through a keyhole in a hotel corridor.

more here.

Not to trigger the ol’ existential panic, but 2023 is drawing to a close quite soon. That means it’s time to tally what the year in movies has brought us. So far, we’ve seen Wes Anderson

Not to trigger the ol’ existential panic, but 2023 is drawing to a close quite soon. That means it’s time to tally what the year in movies has brought us. So far, we’ve seen Wes Anderson  C

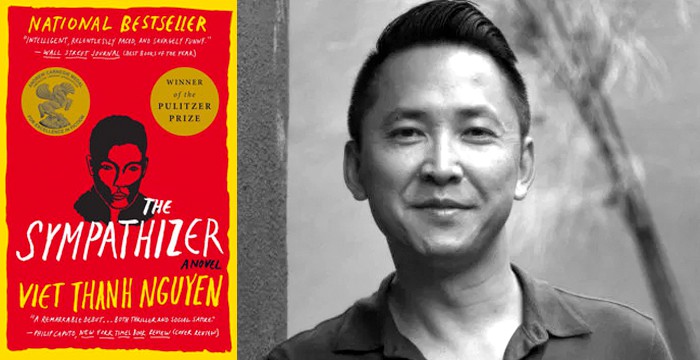

C The modern age, Edward W. Said poignantly observes, is largely the age of the refugee, an era of displaced people from mass immigration. Writing about what it means to be a refugee, he admits, is, however, deceptively hard. Because the anguish of existing in a permanent state of homelessness is a predicament that most people rarely experience frsthand, there is often a tendency to objectify the pain, to make the experience “aesthetically and humanistically comprehensible,” to “banalize its mutilations,” and to understand it as “good for us.” Rare is the literature that can meaningfully and empathetically capture the scale, depth, and magnitude of the suffering of those who are today displaced and rendered homeless by modern warfare, colonialism, and “the quasi-theological ambitions of totalitarian rulers.”2 It is not surprising therefore, as Said suggests, that the most enduring stories about being an exile come from those who have personally been exiled themselves, ones like Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Eqbal Ahmad, Joseph Conrad, and Mahmoud Darwish, who have embodied the experiences of living without a home, without a fxed identity, and without a country. Pulitzer Prize-winning Vietnamese American writer and academic Viet Thanh Nguyen, a refugee himself, is one such rare voice in American literature today, a voice that has been a relentless force in making visible, through storytelling, the highly diverse and multifaceted experiences of Vietnamese refugees arriving, settling, and living in diferent parts of the United States since the Fall of Saigon in 1975.

The modern age, Edward W. Said poignantly observes, is largely the age of the refugee, an era of displaced people from mass immigration. Writing about what it means to be a refugee, he admits, is, however, deceptively hard. Because the anguish of existing in a permanent state of homelessness is a predicament that most people rarely experience frsthand, there is often a tendency to objectify the pain, to make the experience “aesthetically and humanistically comprehensible,” to “banalize its mutilations,” and to understand it as “good for us.” Rare is the literature that can meaningfully and empathetically capture the scale, depth, and magnitude of the suffering of those who are today displaced and rendered homeless by modern warfare, colonialism, and “the quasi-theological ambitions of totalitarian rulers.”2 It is not surprising therefore, as Said suggests, that the most enduring stories about being an exile come from those who have personally been exiled themselves, ones like Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Eqbal Ahmad, Joseph Conrad, and Mahmoud Darwish, who have embodied the experiences of living without a home, without a fxed identity, and without a country. Pulitzer Prize-winning Vietnamese American writer and academic Viet Thanh Nguyen, a refugee himself, is one such rare voice in American literature today, a voice that has been a relentless force in making visible, through storytelling, the highly diverse and multifaceted experiences of Vietnamese refugees arriving, settling, and living in diferent parts of the United States since the Fall of Saigon in 1975. In July 2022, a pair of mathematicians in Belgium startled the cybersecurity world. They took a data-encryption scheme that had been designed to withstand attacks from quantum computers so sophisticated they don’t yet exist, and broke it in 10 minutes using a nine-year-old, non-quantum PC.

In July 2022, a pair of mathematicians in Belgium startled the cybersecurity world. They took a data-encryption scheme that had been designed to withstand attacks from quantum computers so sophisticated they don’t yet exist, and broke it in 10 minutes using a nine-year-old, non-quantum PC. Project Syndicate: You,

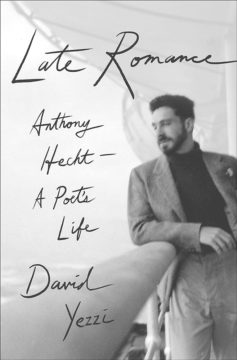

Project Syndicate: You,  He constructed something else to go along with his literary life, too: he created a persona, what we might almost call a carapace. In an academic career that took him on what he called “many years of pilgrimage over the academic map,” from Smith to Bard to Rochester to Georgetown, he adopted the dress and mannerisms of an English gentleman, perhaps in response to what he called the “covert anti-semitism” in some of the departments in which he taught. Beginning his career at a time when creative writers were still viewed with some suspicion by their more conventionally trained colleagues, Hecht compensated by becoming what Yezzi calls “the very model of a modern literature professor: bearded, tweedy, pensive, reserved.” Hecht gravitated to teaching Shakespeare more than creative writing. While his love of Shakespeare was deep-seated, it was also an important part of this process of self-creation. “Nothing could be more canonical” than Shakespeare, Yezzi writes, nothing “more revered and accepted on both intellectual and aesthetic grounds.”

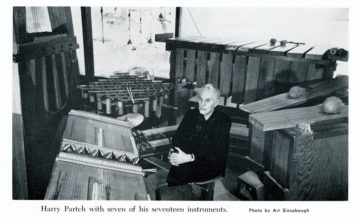

He constructed something else to go along with his literary life, too: he created a persona, what we might almost call a carapace. In an academic career that took him on what he called “many years of pilgrimage over the academic map,” from Smith to Bard to Rochester to Georgetown, he adopted the dress and mannerisms of an English gentleman, perhaps in response to what he called the “covert anti-semitism” in some of the departments in which he taught. Beginning his career at a time when creative writers were still viewed with some suspicion by their more conventionally trained colleagues, Hecht compensated by becoming what Yezzi calls “the very model of a modern literature professor: bearded, tweedy, pensive, reserved.” Hecht gravitated to teaching Shakespeare more than creative writing. While his love of Shakespeare was deep-seated, it was also an important part of this process of self-creation. “Nothing could be more canonical” than Shakespeare, Yezzi writes, nothing “more revered and accepted on both intellectual and aesthetic grounds.” In winter 1940, beside a highway in the California desert, a reedy man bends down for a closer look at the road’s guardrail, where someone has scribbled graffiti: It’s January twenty-six. I’m freezing. Going home. I’m hungry and broke. I wish I was dead. But today I am a man … The onlooker feels a pang of recognition. He can hear these words in his head—the beginnings of another song.

In winter 1940, beside a highway in the California desert, a reedy man bends down for a closer look at the road’s guardrail, where someone has scribbled graffiti: It’s January twenty-six. I’m freezing. Going home. I’m hungry and broke. I wish I was dead. But today I am a man … The onlooker feels a pang of recognition. He can hear these words in his head—the beginnings of another song. Luca Giomi

Luca Giomi Of all the culprits that make it harder for Americans to afford and access

Of all the culprits that make it harder for Americans to afford and access  For someone working in the culture industries, the only thing worse than having the wrong position on a political controversy is having no position at all. Today’s artists are the high priests of the secular middle classes, with cathedrals (art galleries) in every major city. In recent years, rather than defend free expression and the exploration of

For someone working in the culture industries, the only thing worse than having the wrong position on a political controversy is having no position at all. Today’s artists are the high priests of the secular middle classes, with cathedrals (art galleries) in every major city. In recent years, rather than defend free expression and the exploration of

W

W