Henry Oliver in The Common Reader:

Every year at this time, people making resolutions look to self-help books to guide them in their new goals and ambitions. But our self-help is over-simplified easy optimism, a hangover from the days when How to Win Friends and Influence People defined the genre. It’s a mass of stoicism, wellbeing, minimalism, misunderstood Taoism, and productivity and habit advice. This sort of self-help can often be useful, but it is not a whole way of living. Rules for life and aphorisms are a starting point. The Ten Commandments are the original ten rules for life, but they came with the Bible, one of the largest, most challenging books ever written. The more accessible self-help becomes, the less useful it really is.

Every year at this time, people making resolutions look to self-help books to guide them in their new goals and ambitions. But our self-help is over-simplified easy optimism, a hangover from the days when How to Win Friends and Influence People defined the genre. It’s a mass of stoicism, wellbeing, minimalism, misunderstood Taoism, and productivity and habit advice. This sort of self-help can often be useful, but it is not a whole way of living. Rules for life and aphorisms are a starting point. The Ten Commandments are the original ten rules for life, but they came with the Bible, one of the largest, most challenging books ever written. The more accessible self-help becomes, the less useful it really is.

In so much modern self-help, Seneca and Marie Kondo are co-opted into the same cause of making space in our lives, getting back to ourselves, removing anxiety. This is all a means to an end, not an end in itself. These systems aim at an inner silence you can’t maintain. Self-help so often tells us how to improve our habits for the sake of productivity when it ought to be about the improvement of our mind and the expansion of our consciousness. We need a self-help that shows us how to flourish as a whole person, not one that merely offers advice on improving your work habits and anxiously avoiding anxiety.

More here.

In September, scientists at the Guangzhou Institutes of Biomedicine and Health

In September, scientists at the Guangzhou Institutes of Biomedicine and Health  Margaret Cavendish

Margaret Cavendish A

A MOST AMERICAN SCHOOLCHILDREN

MOST AMERICAN SCHOOLCHILDREN T

T

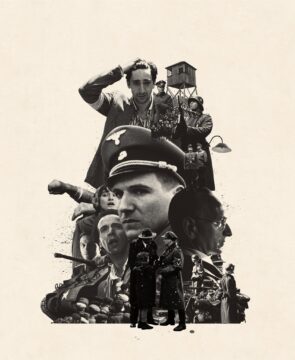

The British philosopher Gillian Rose, who advised the Polish government on how to redesign the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum after the fall of Communism, believed that the new regime of memory was mired in bad faith. By framing the Holocaust as an unfathomable evil — “the ultimate event, the ultimate mystery, never to be comprehended or transmitted,” as the writer Elie Wiesel once put it — we were protecting ourselves, Rose argued, from knowledge of our own capacity for barbarism. “Schindler’s List” was a case in point. For her, Spielberg’s black-and-white epic, which sentimentalizes the Jewish victims and keeps the Nazi perpetrators at arm’s length, was really just a piece of misty-eyed evasion.

The British philosopher Gillian Rose, who advised the Polish government on how to redesign the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum after the fall of Communism, believed that the new regime of memory was mired in bad faith. By framing the Holocaust as an unfathomable evil — “the ultimate event, the ultimate mystery, never to be comprehended or transmitted,” as the writer Elie Wiesel once put it — we were protecting ourselves, Rose argued, from knowledge of our own capacity for barbarism. “Schindler’s List” was a case in point. For her, Spielberg’s black-and-white epic, which sentimentalizes the Jewish victims and keeps the Nazi perpetrators at arm’s length, was really just a piece of misty-eyed evasion. Octopuses, artificial intelligence, and advanced alien civilizations: for many reasons, it’s interesting to contemplate ways of thinking other than whatever it is we humans do. How should we think about the space of all possible cognitions? One aspect is simply the physics of the underlying substrate, the physical stuff that is actually doing the thinking. We are used to brains being solid — squishy, perhaps, but consisting of units in an essentially fixed array. What about liquid brains, where the units can move around? Would an ant colony count? We talk with complexity theorist Ricard Solé about complexity, criticality, and cognition.

Octopuses, artificial intelligence, and advanced alien civilizations: for many reasons, it’s interesting to contemplate ways of thinking other than whatever it is we humans do. How should we think about the space of all possible cognitions? One aspect is simply the physics of the underlying substrate, the physical stuff that is actually doing the thinking. We are used to brains being solid — squishy, perhaps, but consisting of units in an essentially fixed array. What about liquid brains, where the units can move around? Would an ant colony count? We talk with complexity theorist Ricard Solé about complexity, criticality, and cognition. What we have here is the work of a lifetime, a reflective volume alert to local and geopolitics, art and culture, high society and the affairs of ordinary people. If he had served up a larger slice of history, encompassing the consolidation of Stalinism rather than ending the narrative with Lenin’s demise, he could have claimed with some justification to have written the definitive word on the revolution.

What we have here is the work of a lifetime, a reflective volume alert to local and geopolitics, art and culture, high society and the affairs of ordinary people. If he had served up a larger slice of history, encompassing the consolidation of Stalinism rather than ending the narrative with Lenin’s demise, he could have claimed with some justification to have written the definitive word on the revolution.