Category: Recommended Reading

Paula Peatross: Purposefulness With No Purpose

Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe at nonsite:

I think, like quite a few other people, that there are broadly speaking two kinds of art. One is made for and out of propaganda; the other is made with contemplation in mind. All religious and political art belongs to the first category. It tells a story one already knows; the purpose of the art is to give it some specific bias or interpretation that one may or may not already know. The second is not a narrative at all. Instead, it encourages one’s mind to wander, to allow the audience to think and feel for itself. Peatross’s art is of this second sort. There is no story there, no attempt to find Jesus’s face in the pizza. This is not a distinction between nonrepresentational and representational art, but it is one between narrative and nearly everything else. And Peatross’s reliefs are unambiguously nonrepresentational. In addition to not being narratives (stories) of any sort, they are made without reference to anything else outside themselves, such as a landscape, the sole exception to that general rule being that they do preserve the limits and inflexions of her body. That aside, as the artist herself puts it, “Each one is itself.”

more here.

Friday Poem

Aunt Rose

the last

20 years

of her life

after her

mother

died

she sat

at that

kitchen table

hating

the irish

drinking

scotch

mist

&

clipping

obits

loneliness

spread out

in front

of her

like

family

jewels

&

now

years

later

i remember

i had no

kindness

for her

by Jim Bell

from Landing Amazed

Lily Pool Press 2010

What Generative AI Reveals About the Human Mind

Andy Clark in Time Magazine:

Generative AI—think Dall.E, ChatGPT-4, and many more—is all the rage. It’s remarkable successes, and occasional catastrophic failures, have kick-started important debates about both the scope and dangers of advanced forms of artificial intelligence. But what, if anything, does this work reveal about natural intelligences such as our own?

Generative AI—think Dall.E, ChatGPT-4, and many more—is all the rage. It’s remarkable successes, and occasional catastrophic failures, have kick-started important debates about both the scope and dangers of advanced forms of artificial intelligence. But what, if anything, does this work reveal about natural intelligences such as our own?

I’m a philosopher and cognitive scientist who has spent their entire career trying to understand how the human mind works. Drawing on research spanning psychology, neuroscience, and artificial intelligence, my search has drawn me towards a picture of how natural minds work that is both interestingly similar to, yet also deeply different from, the core operating principles of the generative AIs. Examining this contrast may help us better understand them both.

More here.

What counts as plagiarism?

Jeff Tollefson in Nature:

Plagiarism is one of academia’s oldest crimes, but Claudine Gay’s resignation as Harvard University’s president following plagiarism allegations has sparked a fresh online debate: about when copying text should be a punishable offence. Some academics are even advocating for a more streamlined publishing model in which researchers can copy more and write less — so long as the source of the information is clear.

Plagiarism is one of academia’s oldest crimes, but Claudine Gay’s resignation as Harvard University’s president following plagiarism allegations has sparked a fresh online debate: about when copying text should be a punishable offence. Some academics are even advocating for a more streamlined publishing model in which researchers can copy more and write less — so long as the source of the information is clear.

The notion that all researchers must compose their own sentences remains a bedrock principle for many, but that view might encounter new resistance in a world with essentially limitless access to information and increasingly sophisticated artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms that can reproduce language with eerie accuracy. “I think the idea that one should never ever copy somebody else’s words is a bit outdated,” says Lior Pachter, a computational biologist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, adding that the key is to ensure that information is properly sourced. Academia has larger problems, he says, including data fabrication.

More here.

Thursday, January 11, 2024

“The Wizard of the Kremlin” by Giuliano da Empoli: A tsar is born

Marcel Theroux in The Guardian:

Just who is Vladimir Putin? In the 20-odd years he’s been in power, even the Russian leader’s physical appearance has undergone a series of ominous transformations. The alert but colourless apparatchik of his early years first became a smooth-faced enigma, then a tsar of such feline menace that you half expect to see bloody feathers at the corner of his mouth. And that’s nothing compared to the changes that have happened in Russia: at the dawn of the millennium it seemed to be stumbling towards democracy. It had, albeit imperfectly, such things as free speech and opposition politicians. Even Putin seemed to talk sincerely of partnership with his former cold war opponents. So what on earth happened?

Just who is Vladimir Putin? In the 20-odd years he’s been in power, even the Russian leader’s physical appearance has undergone a series of ominous transformations. The alert but colourless apparatchik of his early years first became a smooth-faced enigma, then a tsar of such feline menace that you half expect to see bloody feathers at the corner of his mouth. And that’s nothing compared to the changes that have happened in Russia: at the dawn of the millennium it seemed to be stumbling towards democracy. It had, albeit imperfectly, such things as free speech and opposition politicians. Even Putin seemed to talk sincerely of partnership with his former cold war opponents. So what on earth happened?

One person who is qualified to tell us is the protagonist of Giuliano da Empoli’s gripping debut novel, The Wizard of the Kremlin. His name is Vadim Baranov and he’s the consummate Kremlin insider. Baranov was by Putin’s side as he rose to power and remade Russia. Now he’s retired, a shadowy figure with an extraordinary story to tell.

More here.

How to think like a Bayesian: In a world of few absolutes, it pays to be able to think clearly about probabilities and these five ideas will get you started

Michael G Titelbaum at Psyche:

One of the most important conceptual developments of the past few decades is the realisation that belief comes in degrees. We don’t just believe something or not: much of our thinking, and decision-making, is driven by varying levels of confidence. These confidence levels can be measured as probabilities, on a scale from zero to 100 per cent. When I invest the money I’ve saved for my children’s education, it’s an oversimplification to focus on questions like: ‘Do I believe that stocks will outperform bonds over the next decade, or not?’ I can’t possibly know that. But I can try to assign educated probability estimates to each of those possible outcomes, and balance my portfolio in light of those estimates.

One of the most important conceptual developments of the past few decades is the realisation that belief comes in degrees. We don’t just believe something or not: much of our thinking, and decision-making, is driven by varying levels of confidence. These confidence levels can be measured as probabilities, on a scale from zero to 100 per cent. When I invest the money I’ve saved for my children’s education, it’s an oversimplification to focus on questions like: ‘Do I believe that stocks will outperform bonds over the next decade, or not?’ I can’t possibly know that. But I can try to assign educated probability estimates to each of those possible outcomes, and balance my portfolio in light of those estimates.

We know from many years of studies that reasoning with probabilities is hard. Most of us are raised to reason in all-or-nothing terms. We’re quite capable of expressing intermediate degrees of confidence about events (quick: how confident are you that a Democrat will win the next presidential election?), but we’re very bad at reasoning with those probabilities. Over and over, studies have revealed systematic errors in ordinary people’s probabilistic thinking.

Luckily, there once lived a guy named the Reverend Thomas Bayes.

More here.

Becca Rothfeld speaks with Samuel Moyn about his book “Liberalism Against Itself” and why liberalism is in crisis

Samuel Moyn and Becca Rothfeld in the Boston Review:

Becca Rothfeld: The first question I wanted to ask is how to improve liberalism. Despite some misreadings of Liberalism Against Itself as illiberal, it’s very much not an anti-liberal book. It’s a book that’s disappointed with the direction that postwar liberalism has taken, but it’s also cautiously optimistic about the liberal tradition’s ability to redeem itself.

Becca Rothfeld: The first question I wanted to ask is how to improve liberalism. Despite some misreadings of Liberalism Against Itself as illiberal, it’s very much not an anti-liberal book. It’s a book that’s disappointed with the direction that postwar liberalism has taken, but it’s also cautiously optimistic about the liberal tradition’s ability to redeem itself.

Tallying up your objections to Cold War liberalism in the book, I noticed that it was possible to construct a better ideal of postwar liberalism by imagining a sort of mirror image of the failed liberalism you describe. Could you say a little bit about the positive conception of liberalism glinting in the background of the book?

Samuel Moyn: This book is a series of portraits of liberals in the middle of the twentieth century, and I take a pretty deflationary view of the politics that they wrought. I claim that they introduced a rupture in the history of liberalism. I do imply that they’ve left us, at least in part, in our current situation, intellectually and even practically. I don’t know if I would agree that I’m optimistic about liberalism: I would say that there are resources from the past to draw on before Cold War liberalism that could be used to argue for a new liberalism. But I certainly think that we need to give tough love to liberals, not just for their abuse of their own tradition, but also because they seem recurrently incapable of confronting some nagging criticisms of their platform.

More here.

Dostoevsky vs Nietzsche

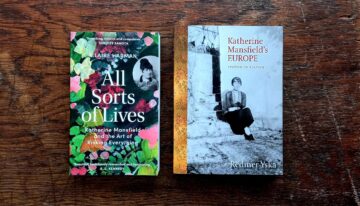

I behave like a fiend

Deborah Friedell in The London Review of Books:

Virginia Woolf wasn’t sure what she felt when she heard that Katherine Mansfield was dead. The cook, ‘in her sensational way’, had broken the news to her at breakfast: ‘Mrs Murry’s dead! It says so in the paper!’

Virginia Woolf wasn’t sure what she felt when she heard that Katherine Mansfield was dead. The cook, ‘in her sensational way’, had broken the news to her at breakfast: ‘Mrs Murry’s dead! It says so in the paper!’

At that one feels – what? A shock of relief? – a rival the less? Then confusion at feeling so little – then, gradually, blankness & disappointment; then a depression which I could not rouse myself from all that day. When I began to write, it seemed to me there was no point in writing. Katherine won’t read it. Katherine’s my rival no longer.

While Mansfield was alive, Woolf had found her ‘cheap and hard’, ‘unpleasant’ and ‘utterly unscrupulous’. It bothered her that she wasn’t sure if Mansfield liked her – letters and invitations often went unanswered. And she sensed that Mansfield was holding something back: ‘We did not ever coalesce.’ But, on balance, she hadn’t wanted her dead, even if she had sometimes wished that she didn’t exist: ‘Damn Katherine! Why can’t I be the only woman who knows how to write?’ She decided that she would have preferred for Mansfield to ‘have written on, & people would have seen that I was the more gifted – that wd. only have become more & more apparent’.

And on Mansfield’s side? ‘How I envy Virginia; no wonder she can write,’ she told her husband, angry that he wouldn’t take care of her the way that Leonard Woolf took care of his wife. ‘That’s one thing I shall grudge Virginia all her days – that she & Leonard were together.’

More here.

Why Incentives to Attract Doctors to Rural Areas Haven’t Worked

Arjun Sharma in Undark:

IN THE 1960s and 1970s, researchers offered financial incentives to patients to get them to lose weight, quit smoking, and abstain from alcohol. To some degree, it worked. But when governmental bodies proffered a pecuniary boon to physicians to move their practice to rural areas, the outcomes were less clear-cut. In fact, new evidence suggests that such monetary incentives barely move the needle.

IN THE 1960s and 1970s, researchers offered financial incentives to patients to get them to lose weight, quit smoking, and abstain from alcohol. To some degree, it worked. But when governmental bodies proffered a pecuniary boon to physicians to move their practice to rural areas, the outcomes were less clear-cut. In fact, new evidence suggests that such monetary incentives barely move the needle.

In 1965, as Medicare was being launched, state lawmakers were in the process of identifying regional gaps in the American health care landscape. These places, which were designated under the nationally established Health Professional Shortage Area program, or HPSA, disproportionately lacked medical practitioners and are now areas where a single physician could be tasked to juggle the health of thousands of people. Such medical deserts include more than 5,300 rural areas, in which almost 33 million people face a dearth of primary care services.

More here.

Margaret Raspé (1933–2023)

Pia-Marie Remmers at Artforum:

FOR THE PAST FIFTY YEARS, artist Margaret Raspé has produced a sensitive, trenchant, and profoundly uncompromising body of work that has, until very recently, received only scant attention.

Born in Wrocław, Poland, Raspé grew up in southern Germany, studying art in the 1950s in Munich before settling in Berlin with her husband. Her budding practice came to a standstill as marriage and motherhood forced Raspé into the traditional role of the housewife. After a divorce in the late 1960s, she found herself with meager financial resources and began renting out her home to artists and theorists of the Fluxus and Viennese Actionism schools. Many of these figures became lasting companions and encouraged Raspé to resume her practice. Raspé’s so-called camera helmet films, which date to the early ’70s, are among her first pieces of this period. Comprising point-of-view shots as the artist prepared schnitzel, washed dishes, or gutted a chicken, they overflow with anger at both the patriarchal structures that dominated her everyday life and her own failure to resist the oppression and alienation that so thoroughly trapped her.

more here.

Kate Zambreno Collects Herself

Katy Waldman at The New Yorker:

Toward the end of “The Light Room,” Kate Zambreno’s memoir of the early pandemic, she describes corresponding with a friend, the author and professor Sofia Samatar, about the difference between hoarding and collecting.

Toward the end of “The Light Room,” Kate Zambreno’s memoir of the early pandemic, she describes corresponding with a friend, the author and professor Sofia Samatar, about the difference between hoarding and collecting.

At this point in the book, Zambreno is thinking about the artist Joseph Cornell—specifically, about how he cleaned out the cellar of his mother’s house in Queens so that he could use it as a workshop. He had to organize the old miscellany and sort it into boxes, which he then gave whimsical labels: “notions,” “cordials,” “wooden balls only.” Zambreno posits that this collecting-and-cataloguing project “became as much a part of [Cornell’s] art as the construction of his collages.” In his diary, she notes, Cornell compared the “creative arrangement” of clutter to a “poetics.”

As is often the case when Zambreno is writing about another artist, she is also implicitly writing about herself.

more here.

Aztec Philosophy With James Maffie

Thursday Poem

Write it on Your Heart

Write it on your heart

that every day is the best day in the year.

He is rich who owns the day,

and no one owns the day

who allows it to be invaded

with fret and anxiety.

Finish every day and be done with it.

You have done what you could.

Some blunders and absurdities,

no doubt crept in.

Forget them as soon as you can,

tomorrow is a new day;

begin it well and serenely,

with too high a spirit

to be cumbered with

your old nonsense.

This new day is too dear,

with its hopes and invitations,

to waste a moment

on the yesterdays.

by Ralph Waldo Emerson

from Poetic Outlaws

Wednesday, January 10, 2024

Wednesday Poem

Immanuel Kant

The philosophy of white blood cells:

this is self,

this in non-self.

The starry sky of non-self,

perfectly mirrored

deep inside.

Immanuel Kant,

perfectly mirrored

deep inside.

And he knows nothing about it,

he is only afraid of drafts.

And he knows nothing about it,

though this is the critique

of pure reason.

Deep inside.

by Miroslav Holub

from The Vintage Book of Contemporary World Poetry

Vintage Books, 1996

On Alexandra Hudson’s “The Soul of Civility”

Alex Bronzini-Vender in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

I understand why many find civility a deeply questionable—if not totally worthless—discourse: cries for civility are often just attempts to silence desperate demands for justice, cloaked in the language of liberal rationality and tolerance. As Martin Luther King Jr. himself famously put it, civility is too often a weapon of the “white moderate, who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.” Many of us are skeptical when someone brings up civility, and for good reason.

I understand why many find civility a deeply questionable—if not totally worthless—discourse: cries for civility are often just attempts to silence desperate demands for justice, cloaked in the language of liberal rationality and tolerance. As Martin Luther King Jr. himself famously put it, civility is too often a weapon of the “white moderate, who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.” Many of us are skeptical when someone brings up civility, and for good reason.

Nevertheless, I found Alexandra Hudson’s new book The Soul of Civility: Timeless Principles to Heal Society and Ourselves unexpectedly compelling. Civility, as Hudson rightly defines it, does not preclude, and even requires, conflict. Hudson writes that civility is rooted in “shared humanity.” To truly recognize someone as your equal, you must be willing to tell them hard truths. And rather than merely bemoaning the loss of vaguely defined civility in American culture, Hudson offers a deeply informed, cross-cultural study of what civility is, and, arguably even more importantly, isn’t.

More here.

Neuroscience is pre-paradigmatic

Eric Hoel in The Intrinsic Perspective:

The hardest question in neuroscience [is] a very simple one, and devastating in its simplicity. If even small artificial neural networks are mathematical black boxes, such that the people who build them don’t know how to control them, nor why they work, nor what their true capabilities are… why do you think that the brain, a higher-parameter and more messy biological neural network, is not similarly a black box?

The hardest question in neuroscience [is] a very simple one, and devastating in its simplicity. If even small artificial neural networks are mathematical black boxes, such that the people who build them don’t know how to control them, nor why they work, nor what their true capabilities are… why do you think that the brain, a higher-parameter and more messy biological neural network, is not similarly a black box?

And if the answer is that it is; indeed, that we should expect even greater opacity from the brain compared to artificial neural networks, then why does every neuroscience textbook not start with that? Because it means neuroscience is not just hard, it’s closing in on impossibly hard for intelligible mathematical reasons. AI researchers struggle with these reasons every day, and that’s despite having perfect access; meanwhile neuroscientists are always three steps removed, their choice of study locked behind blood and bone, with only partial views and poor access. Why is the assumption that you can just fumble at the brain, and that, if enough people are fumbling all together, the truth will reveal itself?

More here.

Your Eco-Friendly Lifestyle Is a Big Lie

Matt Reynolds in Wired:

In 2021 the polling firm Ipsos asked 21,000 people in 30 countries to choose from a list of nine actions which ones they thought would most reduce greenhouse gas emissions for individuals living in a richer country. Most people picked recycling, followed by buying renewable energy, switching to an electric/hybrid car, and opting for low-energy light bulbs. When these actions were ranked by their actual impact on emissions, recycling was third-from-bottom and low-energy light bulbs were last. None of the top-three options selected by people appeared in the “real” top three when ranked by greenhouse gas reductions, which were having one fewer child, not having a car, and avoiding one long-distance flight.

In 2021 the polling firm Ipsos asked 21,000 people in 30 countries to choose from a list of nine actions which ones they thought would most reduce greenhouse gas emissions for individuals living in a richer country. Most people picked recycling, followed by buying renewable energy, switching to an electric/hybrid car, and opting for low-energy light bulbs. When these actions were ranked by their actual impact on emissions, recycling was third-from-bottom and low-energy light bulbs were last. None of the top-three options selected by people appeared in the “real” top three when ranked by greenhouse gas reductions, which were having one fewer child, not having a car, and avoiding one long-distance flight.

This point isn’t that people are dumb; it’s that the most impactful options don’t always intuitively feel that way to us.

More here.