Eli Steele in Newsweek:

The media headlines of the past year suggest that things have gotten a lot worse since 2017—and both Thomas and Fox played a part in the divisiveness. But if you look beyond the headlines, including those on Newsweek, a different picture emerges. Even in what feels like an angry, factionalized society, there are signs of unity.

The media headlines of the past year suggest that things have gotten a lot worse since 2017—and both Thomas and Fox played a part in the divisiveness. But if you look beyond the headlines, including those on Newsweek, a different picture emerges. Even in what feels like an angry, factionalized society, there are signs of unity.

…”My genuine belief is that most Americans don’t really think much about politics, and to the extent they do, they are largely united in the agreement that they dislike it. As a nation, we are far more concerned with celebrity gossip and sports than we are with culture wars or wonkish policy debates. That’s why the average American could almost certainly name more of Pete Davidson’s former lovers than they could members of Congress. Most of the division that we see is manufactured and amplified by a media ecosystem that primarily feeds off of anger and fear. This is particularly true for cable news, which thrives off of a constant stream of outrage porn that rarely befits the designation of journalism. Even so, the fact remains that the overwhelming majority of Americans don’t ever tune in to these outlets. For example, the most successful shows on Fox News, the leader in cable news viewership, only commands an audience that is about one-third the size of the most popular sitcoms on CBS. As a college professor who has taught overtly political topics for years, I’ve also experienced evidence of this united spirit of indifference toward politics that most Americans innately possess. In a classroom of 35 students, maybe four or five on average will routinely speak up and express strong opinions about anything political. The other 85 percent of the class just sits back and hopes they don’t get called on.”

—Nicholas Creel, assistant professor of business law at Georgia College and State University

More here.

S

S Brutalist architecture. You either love it or hate it, right? However you feel, we can all agree that Brutalism is an architectural style that continues to elicit strong reactions some seventy years into its existence. At times, it seems like everyone hates it. Take, for instance, Ian Fleming,

Brutalist architecture. You either love it or hate it, right? However you feel, we can all agree that Brutalism is an architectural style that continues to elicit strong reactions some seventy years into its existence. At times, it seems like everyone hates it. Take, for instance, Ian Fleming,  Nigeria is the

Nigeria is the

One recurring point of contention in political debates is what language we should use to discuss matters of moral and political significance. Many on the progressive left prefer particularist moral language, which emphasizes the specific needs and grievances of particular groups. Others prefer to use universalistic language, which refuses to draw distinctions between groups and focuses on what unites us. The paradigm of this disagreement is the debate between those who prefer the slogan “all lives matter” and those who prefer “black lives matter,” although the conflict is larger than this. For example, many progressives have adopted slogans like “black is beautiful” or “the future is female” that those on the

One recurring point of contention in political debates is what language we should use to discuss matters of moral and political significance. Many on the progressive left prefer particularist moral language, which emphasizes the specific needs and grievances of particular groups. Others prefer to use universalistic language, which refuses to draw distinctions between groups and focuses on what unites us. The paradigm of this disagreement is the debate between those who prefer the slogan “all lives matter” and those who prefer “black lives matter,” although the conflict is larger than this. For example, many progressives have adopted slogans like “black is beautiful” or “the future is female” that those on the  M

M At an

At an  W

W Others explored even darker recesses. In 1925, Alwar’s ruler mowed down five hundred farmers and then torched their village after they had the temerity to protest against his rapacious land tax – an episode far grislier than the Amritsar Massacre of six years earlier. The penultimate ruler of Patiala’s appetite for quail – he devoured twenty-five in a single sitting – was equalled only by his appetite for tax and sex. Some 60 per cent of the state’s income was spent on his sustenance. Bureaucrats were jailed for failing to supply him with a ‘constant stream of young peasant girls for his sexual gratification’. It was left to his son and successor, Yadavindra Singh, to deal with Partition. ‘Death to all Muslims,’ he intoned on learning in 1947 that Pakistan coveted his kingdom, in which Sikhs were the largest group, before leading a conga through his palace. As it was, his problem solved itself. Around the time of Partition, fear whittled down the Muslim population in the Punjab princely states from a million to under fifty thousand. Patiala went to India.

Others explored even darker recesses. In 1925, Alwar’s ruler mowed down five hundred farmers and then torched their village after they had the temerity to protest against his rapacious land tax – an episode far grislier than the Amritsar Massacre of six years earlier. The penultimate ruler of Patiala’s appetite for quail – he devoured twenty-five in a single sitting – was equalled only by his appetite for tax and sex. Some 60 per cent of the state’s income was spent on his sustenance. Bureaucrats were jailed for failing to supply him with a ‘constant stream of young peasant girls for his sexual gratification’. It was left to his son and successor, Yadavindra Singh, to deal with Partition. ‘Death to all Muslims,’ he intoned on learning in 1947 that Pakistan coveted his kingdom, in which Sikhs were the largest group, before leading a conga through his palace. As it was, his problem solved itself. Around the time of Partition, fear whittled down the Muslim population in the Punjab princely states from a million to under fifty thousand. Patiala went to India. Senior Biden administration leaders have self-consciously styled Biden’s approach as a move away from the neoliberal presumptions of the

Senior Biden administration leaders have self-consciously styled Biden’s approach as a move away from the neoliberal presumptions of the  The

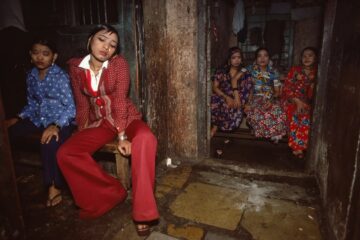

The  Meredith Lue, president of the Mary Ellen Mark Foundation told CNN via video call that the photographer, who experienced a challenging family life in her youth, found herself gravitating toward — and connecting with — people in vulnerable situations.

Meredith Lue, president of the Mary Ellen Mark Foundation told CNN via video call that the photographer, who experienced a challenging family life in her youth, found herself gravitating toward — and connecting with — people in vulnerable situations. “Palestine is a story away.” This is what Refaat Alareer wrote on my copy of the short story anthology he edited in 2014, Gaza Writes Back. The contributors were his students at the Islamic University of Gaza.

“Palestine is a story away.” This is what Refaat Alareer wrote on my copy of the short story anthology he edited in 2014, Gaza Writes Back. The contributors were his students at the Islamic University of Gaza. Every year at this time, people making resolutions look to self-help books to guide them in their new goals and ambitions. But our self-help is over-simplified easy optimism, a hangover from the days when How to Win Friends and Influence People defined the genre. It’s a mass of stoicism, wellbeing, minimalism, misunderstood Taoism, and productivity and habit advice. This sort of self-help can often be useful, but it is not a whole way of living. Rules for life and aphorisms are a starting point. The Ten Commandments are the original ten rules for life, but they came with the Bible, one of the largest, most challenging books ever written. The more accessible self-help becomes, the less useful it really is.

Every year at this time, people making resolutions look to self-help books to guide them in their new goals and ambitions. But our self-help is over-simplified easy optimism, a hangover from the days when How to Win Friends and Influence People defined the genre. It’s a mass of stoicism, wellbeing, minimalism, misunderstood Taoism, and productivity and habit advice. This sort of self-help can often be useful, but it is not a whole way of living. Rules for life and aphorisms are a starting point. The Ten Commandments are the original ten rules for life, but they came with the Bible, one of the largest, most challenging books ever written. The more accessible self-help becomes, the less useful it really is.