Ayanna Dozier in Artsy:

In honor of Black History Month, Artsy is featuring the work of 28 Black artists who are not as widely known or celebrated as some of their historical or contemporary peers. This list is meant to shine a light on artists who have prominence within institutions, but are often excluded from mainstream conversations meant to amplify overlooked Black artists or canonize them as leading figures of art history.

In honor of Black History Month, Artsy is featuring the work of 28 Black artists who are not as widely known or celebrated as some of their historical or contemporary peers. This list is meant to shine a light on artists who have prominence within institutions, but are often excluded from mainstream conversations meant to amplify overlooked Black artists or canonize them as leading figures of art history.

Of course, Alma Thomas, Jack Whitten, Sam Gilliam, and Frank Bowling are well-deserved citations of the early Black abstractionists, but lesser known to that history, broadly speaking, are Lilian Thomas Burwell, Evangeline “EJ” Montgomery, and Deborah Dancey. While contemporary artists like Kerry James Marshall, Betye Saar, and Faith Ringgold are the founding leaders of contemporary figurative painting and printmaking, the contributions of artists like Malcolm Bailey, Charles Alston, and Camille Billops may not be as widely discussed. We hope this will serve as an introduction to, rather than a comprehensive list of, Black artists whose legacies deserve to be cemented in art history and public consciousness. Here are 28 need-to-know Black artists from the 20th and 21st centuries.

More here. (Note: In honor of Black History Month, at least one post will be devoted to its 2024 theme of “African Americans and the Arts” throughout the month of February)

I have a friend who, before she ran from Kyiv as Russia bombarded the city in early 2022, spent weeks shivering in the bomb shelters as the city was shelled.

I have a friend who, before she ran from Kyiv as Russia bombarded the city in early 2022, spent weeks shivering in the bomb shelters as the city was shelled. Although bestiaries were popular texts in medieval Europe, many of their tales derive from a far older text from northern Africa known as the Physiologus. The Physiologus (meaning Natural Philosopher) was originally written in Greek by an unknown author, probably someone living in Alexandria during the third century CE. This text in turn is made up of stories whose influences can be traced even further back in time to texts on natural philosophy and religion by ancient Greek and Roman writers.

Although bestiaries were popular texts in medieval Europe, many of their tales derive from a far older text from northern Africa known as the Physiologus. The Physiologus (meaning Natural Philosopher) was originally written in Greek by an unknown author, probably someone living in Alexandria during the third century CE. This text in turn is made up of stories whose influences can be traced even further back in time to texts on natural philosophy and religion by ancient Greek and Roman writers. Throughout the late 1960s and ’70s, the heyday of Arte Povera and European conceptualism, Anselmo continued to create objects that use the slightest material intervention as a means to heighten viewers’ awareness of the relativity of human existence and the natural forces that determine it. They provoke interrogation without offering resolution. He was invited to take part in Daniela Palazzoli’s groundbreaking Con temp l’azione—a punning title that refers to both contemplation and time-based actions—which was an exhibition that spanned three different Turin galleries and issued a foldout broadsheet as its catalogue. Fittingly, Anselmo created works for this show that reinforced reflection on the way we exist in a nexus of natural and built environments. Direzione (Direction), 1967–68, for instance, is a low triangular slab of schist with a small compass embedded in its surface. The stone is a metamorphic rock, meaning it was formed in response to environmental heat or pressure, and the compass responds to Earth’s magnetic field, indicating the point of reference we call North. Brought together into this succinct arrangement, which reflects the logic of Duchamp’s assisted readymades, the natural material and the manufactured tool offer palpable traces of the ever-present natural forces that determine our sense of the world, even in the supposedly neutral white cube of the gallery.

Throughout the late 1960s and ’70s, the heyday of Arte Povera and European conceptualism, Anselmo continued to create objects that use the slightest material intervention as a means to heighten viewers’ awareness of the relativity of human existence and the natural forces that determine it. They provoke interrogation without offering resolution. He was invited to take part in Daniela Palazzoli’s groundbreaking Con temp l’azione—a punning title that refers to both contemplation and time-based actions—which was an exhibition that spanned three different Turin galleries and issued a foldout broadsheet as its catalogue. Fittingly, Anselmo created works for this show that reinforced reflection on the way we exist in a nexus of natural and built environments. Direzione (Direction), 1967–68, for instance, is a low triangular slab of schist with a small compass embedded in its surface. The stone is a metamorphic rock, meaning it was formed in response to environmental heat or pressure, and the compass responds to Earth’s magnetic field, indicating the point of reference we call North. Brought together into this succinct arrangement, which reflects the logic of Duchamp’s assisted readymades, the natural material and the manufactured tool offer palpable traces of the ever-present natural forces that determine our sense of the world, even in the supposedly neutral white cube of the gallery.

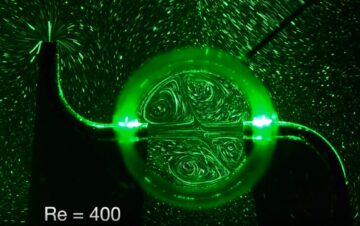

A typical lawn sprinkler features various nozzles arranged at angles on a rotating wheel; when water is pumped in, they release jets that cause the wheel to rotate. But what would happen if the water were sucked into the sprinkler instead? In which direction would the wheel turn then, or would it even turn at all? That’s the essence of the “

A typical lawn sprinkler features various nozzles arranged at angles on a rotating wheel; when water is pumped in, they release jets that cause the wheel to rotate. But what would happen if the water were sucked into the sprinkler instead? In which direction would the wheel turn then, or would it even turn at all? That’s the essence of the “ Good news for Joe Biden this week. Job gains beat forecasts and the phrase “surprisingly strong economy” once again appeared in headlines. Voters mostly refused to acknowledge the good news through 2023 but the latest consumer sentiment surveys suggest the sunshine is finally penetrating the gloom. Optimism is rising. If the economy maintains course through 2024, Biden, for all his faults and weaknesses, will be the heavy favourite for re-election.

Good news for Joe Biden this week. Job gains beat forecasts and the phrase “surprisingly strong economy” once again appeared in headlines. Voters mostly refused to acknowledge the good news through 2023 but the latest consumer sentiment surveys suggest the sunshine is finally penetrating the gloom. Optimism is rising. If the economy maintains course through 2024, Biden, for all his faults and weaknesses, will be the heavy favourite for re-election. A preventative anti-aging therapy seems like wishful thinking. Yet

A preventative anti-aging therapy seems like wishful thinking. Yet  Martha Nussbaum: I’ll first say what most people think it is (I have a rather different view). The general idea started with Socrates, who thought most people don’t pause to think and they don’t summon their beliefs into explicitness and therefore are guided by custom, convention, and authority, and have never stopped to sort out what they really think. So what most people who teach moral philosophy do is just try to conduct that kind of Socratic inquiry, get people to be more critical, more conscious, and, therefore, to discuss with others more in that spirit of critical awareness, rather than just saying, “Oh, I think this.”

Martha Nussbaum: I’ll first say what most people think it is (I have a rather different view). The general idea started with Socrates, who thought most people don’t pause to think and they don’t summon their beliefs into explicitness and therefore are guided by custom, convention, and authority, and have never stopped to sort out what they really think. So what most people who teach moral philosophy do is just try to conduct that kind of Socratic inquiry, get people to be more critical, more conscious, and, therefore, to discuss with others more in that spirit of critical awareness, rather than just saying, “Oh, I think this.” Since ancient times, plants’ ability to orient their eyeless bodies toward the nearest, brightest source of light — known today as phototropism — has fascinated scholars and generated countless scientific and philosophical debates. And over the past 150 years, botanists have successfully unraveled many of the key molecular pathways that underpin how plants sense light and act on that information.

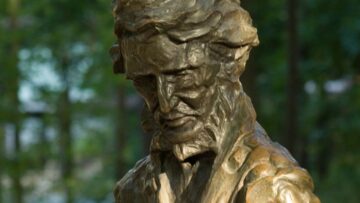

Since ancient times, plants’ ability to orient their eyeless bodies toward the nearest, brightest source of light — known today as phototropism — has fascinated scholars and generated countless scientific and philosophical debates. And over the past 150 years, botanists have successfully unraveled many of the key molecular pathways that underpin how plants sense light and act on that information. On July 4, 1845, a man from Concord, Massachusetts, declared his own independence and went into the woods nearby. On the shore of a pond there, Henry David Thoreau built a small wooden cabin, which he would call home for two years, two months and two days. From this base he began a philosophical project of “deliberate” living, intending to “earn [a] living by the labor of my hands only”. Though an ostensibly radical undertaking, this experiment was not a break with his past, but the logical culmination of years of searching and groping. Since graduating from Harvard in 1837 Thoreau had tried out many ways of earning his keep, and fortunately proved competent in almost everything he set his mind to. Asked once to describe his professional situation, he responded: “I don’t know whether mine is a profession, or a trade, or what not … I am a schoolmaster, a private tutor, a surveyor, a gardener, a farmer, a painter (I mean a house-painter), a carpenter, a mason, a day-laborer, a pencil-maker, a glass-paper-maker, a writer, and sometimes a poetaster”.

On July 4, 1845, a man from Concord, Massachusetts, declared his own independence and went into the woods nearby. On the shore of a pond there, Henry David Thoreau built a small wooden cabin, which he would call home for two years, two months and two days. From this base he began a philosophical project of “deliberate” living, intending to “earn [a] living by the labor of my hands only”. Though an ostensibly radical undertaking, this experiment was not a break with his past, but the logical culmination of years of searching and groping. Since graduating from Harvard in 1837 Thoreau had tried out many ways of earning his keep, and fortunately proved competent in almost everything he set his mind to. Asked once to describe his professional situation, he responded: “I don’t know whether mine is a profession, or a trade, or what not … I am a schoolmaster, a private tutor, a surveyor, a gardener, a farmer, a painter (I mean a house-painter), a carpenter, a mason, a day-laborer, a pencil-maker, a glass-paper-maker, a writer, and sometimes a poetaster”. For many progressives, it was a big moment. In 2019, Congress was holding its first

For many progressives, it was a big moment. In 2019, Congress was holding its first  Since the late 1970s,

Since the late 1970s,