Dwight Garner in The New York Times:

The Mexican writer Álvaro Enrigue’s new novel has a soft, nebulous title: “You Dreamed of Empires.” Its cover is forgettable, too. Like nearly every book on the New Fiction table, it is all wavy patterns and beach-towel colors. This generic look has come to promise a) bright settings and b) young characters out to conquer racial and sexual threats as they perceive them. This would be excellent were it not for, as often as not, c) writing in which one is instructed how to feel at almost every moment.

The Mexican writer Álvaro Enrigue’s new novel has a soft, nebulous title: “You Dreamed of Empires.” Its cover is forgettable, too. Like nearly every book on the New Fiction table, it is all wavy patterns and beach-towel colors. This generic look has come to promise a) bright settings and b) young characters out to conquer racial and sexual threats as they perceive them. This would be excellent were it not for, as often as not, c) writing in which one is instructed how to feel at almost every moment.

What a treat, then, to find that “You Dreamed of Empires” is not wet but dry. It is also short, strange, spiky and sublime. It’s a historical novel, a great speckled bird of a story, set in 1519 in what is now Mexico City. Empires are in collision and the vibe is hallucinatory. The Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés has arrived with his troops and an enormous retinue, pesky supernumeraries who’ve attached themselves to him like remoras, or dingleberries.

He is expecting to meet the Aztec emperor Moctezuma, who is fearsome yet depressed. The aging Moctezuma tends to be either napping or maxed out on magic mushrooms — or both. Increasingly, he is getting in touch with what Homer Simpson referred to as his womanly needs. The kill count promises to be enormous. In the first scene we meet priests who casually wear human skin as veils. Their hair is crusted with layers of sacrificial blood; one has teeth “filed sharp as a cat’s.” Fickle gods must be appeased. Human sacrifice is common; hearts are ripped out, the unlucky cored as if they were apples. Strips of warrior loin are said, by 16th-century epicures, to be yummy on a tostada.

More here.

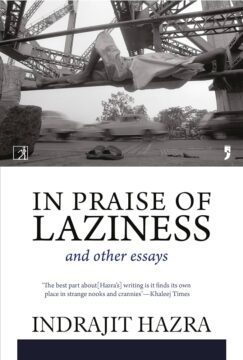

In a 1972 interview conducted by Amitabh Basu in his column ‘Dainandin Jibone’ (In Everyday Life) where in every issue of the film magazine, Ultoroth, Basu posed a set list of questions to writers, Shibram had articulated the nous of laziness. Replying to the very first question, ‘When do you get up in the morning?’ he sets the warp, woof and tone:

In a 1972 interview conducted by Amitabh Basu in his column ‘Dainandin Jibone’ (In Everyday Life) where in every issue of the film magazine, Ultoroth, Basu posed a set list of questions to writers, Shibram had articulated the nous of laziness. Replying to the very first question, ‘When do you get up in the morning?’ he sets the warp, woof and tone:

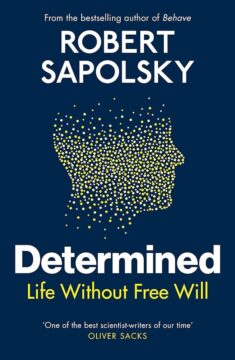

Robert M. Sapolsky is a professor of biology and neurology who you may remember from his 2017 best-seller

Robert M. Sapolsky is a professor of biology and neurology who you may remember from his 2017 best-seller  Beginning in the late 1860s, the decade that it took to construct the Suez Canal, photographs depicting its feats of engineering circulated across the world. Sold to travelers as souvenirs, featured in Le Monde, and later exhibited at the 1889 Paris world fair, they enshrined on paper the industrial monumentality of the dredgers that excavated earth into sea.

Beginning in the late 1860s, the decade that it took to construct the Suez Canal, photographs depicting its feats of engineering circulated across the world. Sold to travelers as souvenirs, featured in Le Monde, and later exhibited at the 1889 Paris world fair, they enshrined on paper the industrial monumentality of the dredgers that excavated earth into sea. Payne is America’s poet laureate of losers. Over thirty years, the writer-director has sheltered a menagerie of the bumbling, the henpecked, the ineffectual, the distressed, and the depressed. Payne lists both Italian neo-realism and American movies of the 1970s (he was born in 1961) as influences. But his films bear a stamp all his own. Their hallmark elements include a fondness for voiceovers; a reliance on music as an active arm of storytelling; a use of both professional actors and non-actors; a commitment to character-forward stories, adapted from novels, that emphasize place and character; and, above all, a balancing, or mingling, or juxtaposition, of disparate tones and intentions.

Payne is America’s poet laureate of losers. Over thirty years, the writer-director has sheltered a menagerie of the bumbling, the henpecked, the ineffectual, the distressed, and the depressed. Payne lists both Italian neo-realism and American movies of the 1970s (he was born in 1961) as influences. But his films bear a stamp all his own. Their hallmark elements include a fondness for voiceovers; a reliance on music as an active arm of storytelling; a use of both professional actors and non-actors; a commitment to character-forward stories, adapted from novels, that emphasize place and character; and, above all, a balancing, or mingling, or juxtaposition, of disparate tones and intentions. In Cave’s weltanschauung, as laid out in the letter, the machine is a priori precluded from participating in the authentic creative act, because it is not, well, human. If this argument sounds hollow and slightly narcissistic, that’s because it is. It follows a circular logic: humans (and Nick Cave) are special because they alone make art, and art is special because it is alone made by humans (and Nick Cave). His argument is also totally familiar and banal—a platitude so endlessly repeated in contemporary discourse that it feels in some way hard-baked into the culture. According to historians of ideas (see Arthur Lovejoy, Isaiah Berlin, Alfred North Whitehead), this thesis took form sometime in the second half of the eighteenth century. A brief and noncomprehensive summary: to preserve human dignity in the face of industrialization, philosophers and poets, who were later called the Romantics, began to redraw ontological boundaries, placing humans, nature, and art on one side, and machines, industry, and rationalism on the other. Poets became paragons of the human, and their poems examples of that which could never be replicated by the machine. William Blake, for instance, one of Cave’s heroes, proposed that if it were not for the “Poetic or Prophetic character,” the universe would become but a “mill with complicated wheels.”

In Cave’s weltanschauung, as laid out in the letter, the machine is a priori precluded from participating in the authentic creative act, because it is not, well, human. If this argument sounds hollow and slightly narcissistic, that’s because it is. It follows a circular logic: humans (and Nick Cave) are special because they alone make art, and art is special because it is alone made by humans (and Nick Cave). His argument is also totally familiar and banal—a platitude so endlessly repeated in contemporary discourse that it feels in some way hard-baked into the culture. According to historians of ideas (see Arthur Lovejoy, Isaiah Berlin, Alfred North Whitehead), this thesis took form sometime in the second half of the eighteenth century. A brief and noncomprehensive summary: to preserve human dignity in the face of industrialization, philosophers and poets, who were later called the Romantics, began to redraw ontological boundaries, placing humans, nature, and art on one side, and machines, industry, and rationalism on the other. Poets became paragons of the human, and their poems examples of that which could never be replicated by the machine. William Blake, for instance, one of Cave’s heroes, proposed that if it were not for the “Poetic or Prophetic character,” the universe would become but a “mill with complicated wheels.” V

V An

An  A colophon is the design or symbol publishers place on the spines of their books. Glance at your bookshelves, at the bottom edge of each volume, and you might see the Knopf borzoi, the three fish of FSG, the interlocking geometric shapes of Graywolf. They are designed to be

A colophon is the design or symbol publishers place on the spines of their books. Glance at your bookshelves, at the bottom edge of each volume, and you might see the Knopf borzoi, the three fish of FSG, the interlocking geometric shapes of Graywolf. They are designed to be  The social cost of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, considered the single most important measure in addressing the climate crisis, is generally defined as an estimate of societal damages, including health harms, resulting from unpaid or externalized GHG emissions. Researchers have been calculating this cost

The social cost of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, considered the single most important measure in addressing the climate crisis, is generally defined as an estimate of societal damages, including health harms, resulting from unpaid or externalized GHG emissions. Researchers have been calculating this cost  Hutchison wore the trash company’s jumpsuit, cap and reflective vest, and he sported a few days of beard stubble. He was collecting trash hoping to find something valuable: the DNA of a person who might prove to be a suspect in the sexual assault and murder of an 18-year-old security guard in Sunnyvale in 1969.

Hutchison wore the trash company’s jumpsuit, cap and reflective vest, and he sported a few days of beard stubble. He was collecting trash hoping to find something valuable: the DNA of a person who might prove to be a suspect in the sexual assault and murder of an 18-year-old security guard in Sunnyvale in 1969. Watching lawyers for

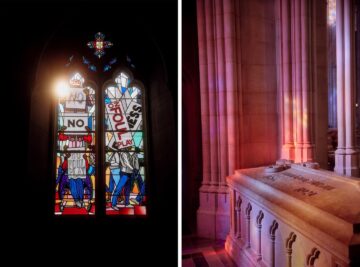

Watching lawyers for  On March 31, 1968, days before he would be assassinated, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

On March 31, 1968, days before he would be assassinated, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.  The Mexican writer Álvaro Enrigue’s new novel has a soft, nebulous title: “You Dreamed of Empires.” Its cover is forgettable, too. Like nearly every book on the New Fiction table, it is all wavy patterns and beach-towel colors. This generic look has come to promise a) bright settings and b) young characters out to conquer racial and sexual threats as they perceive them. This would be excellent were it not for, as often as not, c) writing in which one is instructed how to feel at almost every moment.

The Mexican writer Álvaro Enrigue’s new novel has a soft, nebulous title: “You Dreamed of Empires.” Its cover is forgettable, too. Like nearly every book on the New Fiction table, it is all wavy patterns and beach-towel colors. This generic look has come to promise a) bright settings and b) young characters out to conquer racial and sexual threats as they perceive them. This would be excellent were it not for, as often as not, c) writing in which one is instructed how to feel at almost every moment.