Sharon Brous in The New York Times:

A somewhat obscure text, about 2,000 years old, has been my unlikely teacher and guide for the past many years, and my north star these last several months, as so many of us have felt as if we’ve been drowning in an ocean of sorrow and helplessness. Buried deep within the Mishnah, a Jewish legal compendium from around the third century, is an ancient practice reflecting a deep understanding of the human psyche and spirit: When your heart is broken, when the specter of death visits your family, when you feel lost and alone and inclined to retreat, you show up. You entrust your pain to the community. The text, Middot 2:2, describes a pilgrimage ritual from the time of the Second Temple. Several times each year, hundreds of thousands of Jews would ascend to Jerusalem, the center of Jewish religious and political life. They would climb the steps of the Temple Mount and enter its enormous plaza, turning to the right en masse, circling counterclockwise. Meanwhile, the brokenhearted, the mourners (and here I would also include the lonely and the sick), would make this same ritual walk but they would turn to the left and circle in the opposite direction: every step against the current.

A somewhat obscure text, about 2,000 years old, has been my unlikely teacher and guide for the past many years, and my north star these last several months, as so many of us have felt as if we’ve been drowning in an ocean of sorrow and helplessness. Buried deep within the Mishnah, a Jewish legal compendium from around the third century, is an ancient practice reflecting a deep understanding of the human psyche and spirit: When your heart is broken, when the specter of death visits your family, when you feel lost and alone and inclined to retreat, you show up. You entrust your pain to the community. The text, Middot 2:2, describes a pilgrimage ritual from the time of the Second Temple. Several times each year, hundreds of thousands of Jews would ascend to Jerusalem, the center of Jewish religious and political life. They would climb the steps of the Temple Mount and enter its enormous plaza, turning to the right en masse, circling counterclockwise. Meanwhile, the brokenhearted, the mourners (and here I would also include the lonely and the sick), would make this same ritual walk but they would turn to the left and circle in the opposite direction: every step against the current.

And each person who encountered someone in pain would look into that person’s eyes and inquire: “What happened to you? Why does your heart ache?” “My father died,” a person might say. “There are so many things I never got to say to him.” Or perhaps: “My partner left. I was completely blindsided.” Or: “My child is sick. We’re awaiting the test results.” Those who walked from the right would offer a blessing: “May the Holy One comfort you,” they would say. “You are not alone.” And then they would continue to walk until the next person approached.

This timeless wisdom speaks to what it means to be human in a world of pain. This year, you walk the path of the anguished. Perhaps next year, it will be me. I hold your broken heart knowing that one day you will hold mine.

More here.

A

A I had two memorable experiences with the moon this year. The first was seeing the

I had two memorable experiences with the moon this year. The first was seeing the  It struck me recently that it’s been quite some time since I last heard anyone speak of the importance of maintaining a “work/life balance”. Like co-dependency, like low blood-sugar,

It struck me recently that it’s been quite some time since I last heard anyone speak of the importance of maintaining a “work/life balance”. Like co-dependency, like low blood-sugar, This might sound as though Lincowski is a crime-fighting hunter of aliens in a Marvel superhero film, and that interpretation isn’t far off. Until the end of last year, Lincowski worked as a police detective in Casper, Wyoming, from Monday to Thursday. And on Fridays, he looked for signs of life on planets beyond the Solar System, as part of a research team at the University of Washington in Seattle. Earlier this month, he started working as a mathematician at Eastern Wyoming College in Torrington, where he will be teaching mainly 18–21-year-old students. However, he will continue his one-day-a-week planetary science research at Washington.

This might sound as though Lincowski is a crime-fighting hunter of aliens in a Marvel superhero film, and that interpretation isn’t far off. Until the end of last year, Lincowski worked as a police detective in Casper, Wyoming, from Monday to Thursday. And on Fridays, he looked for signs of life on planets beyond the Solar System, as part of a research team at the University of Washington in Seattle. Earlier this month, he started working as a mathematician at Eastern Wyoming College in Torrington, where he will be teaching mainly 18–21-year-old students. However, he will continue his one-day-a-week planetary science research at Washington. GAZANS HAVE INDEED SOUGHT OUR EYES and attention amid these days of peril. Defying Israel’s

GAZANS HAVE INDEED SOUGHT OUR EYES and attention amid these days of peril. Defying Israel’s  Architectural historians can easily stray into advocacy. Consider Sigfried Giedion, the Swiss author of Space, Time and Architecture and a self-appointed propagandist of early Modernism, or Henry-Russell Hitchcock, who with Philip Johnson curated the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art that launched the International Style in the United States. The late Vincent Scully, a Hitchcock student and longtime Yale professor of architectural history, was an advocate too, one of his early forays into advocacy being a book provocatively titled The Shingle Style Today: Or the Historian’s Revenge.

Architectural historians can easily stray into advocacy. Consider Sigfried Giedion, the Swiss author of Space, Time and Architecture and a self-appointed propagandist of early Modernism, or Henry-Russell Hitchcock, who with Philip Johnson curated the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art that launched the International Style in the United States. The late Vincent Scully, a Hitchcock student and longtime Yale professor of architectural history, was an advocate too, one of his early forays into advocacy being a book provocatively titled The Shingle Style Today: Or the Historian’s Revenge. SAM GILLIAM’S 1980 painting Robbin’ Peter seethes with pigment. The colors densely clot in some areas and in others are scraped flat to reveal the weave of the raw fabric canvas. Reds and blues clump and splat and drip, interrupted by short linear marks dragged through the paint to create rhythmic grooves. The work is a puzzle-like collage of previous Gilliam paintings, which have been cut up, reassembled, and glued in patchwork-quilt fashion, and in fact it takes its name from a vernacular quilt pattern known as “Robbing Peter to Pay Paul”—conventionally, a two-color needlework with curved diamond seams and overlapping, interlocked quartered circles. The pattern is found on quilts across the United States from the nineteenth century to the present day and is sometimes called simply, as Gilliam’s title acknowledges, “Robbing Peter.”1 Part of “Chasers,” a series of nine-sided works that Gilliam made between circa 1980 and 1982, pursuing in the process his always restless experiments with texture, shape, and surface, the quilt painting is muscular and assertive, pressing into space with its thick, built-up impasto excrescences.

SAM GILLIAM’S 1980 painting Robbin’ Peter seethes with pigment. The colors densely clot in some areas and in others are scraped flat to reveal the weave of the raw fabric canvas. Reds and blues clump and splat and drip, interrupted by short linear marks dragged through the paint to create rhythmic grooves. The work is a puzzle-like collage of previous Gilliam paintings, which have been cut up, reassembled, and glued in patchwork-quilt fashion, and in fact it takes its name from a vernacular quilt pattern known as “Robbing Peter to Pay Paul”—conventionally, a two-color needlework with curved diamond seams and overlapping, interlocked quartered circles. The pattern is found on quilts across the United States from the nineteenth century to the present day and is sometimes called simply, as Gilliam’s title acknowledges, “Robbing Peter.”1 Part of “Chasers,” a series of nine-sided works that Gilliam made between circa 1980 and 1982, pursuing in the process his always restless experiments with texture, shape, and surface, the quilt painting is muscular and assertive, pressing into space with its thick, built-up impasto excrescences. As a sophomore in college, I completely earned the C+ that I received in a survey course called “British Literature.” There could be no blaming of the professor on my end, no skirting responsibility for those missed assignments, no excuse for having confused Belphoebe for Gloriana in Edmund Spenser’s

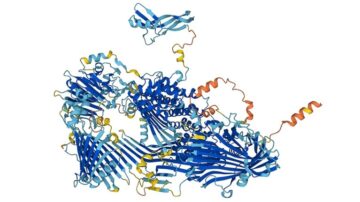

As a sophomore in college, I completely earned the C+ that I received in a survey course called “British Literature.” There could be no blaming of the professor on my end, no skirting responsibility for those missed assignments, no excuse for having confused Belphoebe for Gloriana in Edmund Spenser’s  Researchers have used the protein-structure-prediction tool AlphaFold to identify

Researchers have used the protein-structure-prediction tool AlphaFold to identify Your napkins need to be folded in a way that suggests you hold a degree in structural engineering.

Your napkins need to be folded in a way that suggests you hold a degree in structural engineering.