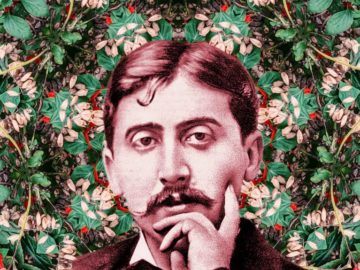

One hundred years ago, on Nov. 18, 1922, Marcel Proust breathed his last in Paris at age 51. His death, from pneumonia and a pulmonary abscess, was perhaps the final nail in the coffin of the belle epoque, an age of gentility, civility and artistic achievement that had mostly ended with the outbreak of World War I. At the time, several volumes of Proust’s gargantuan, seven-part novel, “À la recherche du temps perdu” (“In Search of Lost Time”), had yet to be published. Jean Cocteau, arriving to pay tribute to the late author, spotted the manuscript resting on the mantelpiece — a pile of papers “still alive, like watches ticking on the wrists of dead soldiers.” Proust’s death was an ending but not the end. It would be five more years before “In Search” was published in full and decades before an authoritative text was established from the morass of his marginalia. His work has since been widely acclaimed, and a Proust-industrial complex of criticism and biography has developed around him. “No one is less dead than he is,” a friend remarked, some years after his demise.

One hundred years ago, on Nov. 18, 1922, Marcel Proust breathed his last in Paris at age 51. His death, from pneumonia and a pulmonary abscess, was perhaps the final nail in the coffin of the belle epoque, an age of gentility, civility and artistic achievement that had mostly ended with the outbreak of World War I. At the time, several volumes of Proust’s gargantuan, seven-part novel, “À la recherche du temps perdu” (“In Search of Lost Time”), had yet to be published. Jean Cocteau, arriving to pay tribute to the late author, spotted the manuscript resting on the mantelpiece — a pile of papers “still alive, like watches ticking on the wrists of dead soldiers.” Proust’s death was an ending but not the end. It would be five more years before “In Search” was published in full and decades before an authoritative text was established from the morass of his marginalia. His work has since been widely acclaimed, and a Proust-industrial complex of criticism and biography has developed around him. “No one is less dead than he is,” a friend remarked, some years after his demise.

Though Proust is unignorable, he’s often neglected; his reputation for being difficult can put off even ambitious readers. In a world hellbent on decimating our attention spans, however, immersion in Proust offers significant spiritual benefits. Indeed, the polite demands he makes on concentration and commitment are handsomely repaid in revelation and insight. And to read him is to join an eclectic, brilliant band of fellow travelers. Virginia Woolf and Samuel Beckett were early admirers. Edith Wharton said that Proust gave Henry James “his last, and one of his strongest, artistic emotions.”

More here.